Introduction

Nowadays, women dynamically develop their careers and pursue their passions. This involves personal fulfilment, but also increasing pressures, also internal ones (Zhang S., Lu, Kang, Zhang, X., 2020; Jones, Clair, King, Humberd, Arena, 2020). The birth of a child is a special moment that for many women and also one of the more stressful experiences of their lives. The perinatal period brings many changes not only to a woman’s body but also to her mental health, affecting her wellbeing and her roles in everyday life (Fathi, Mohammad-Alizadeh-Charandabi, Mirghafourvand, 2018; Bręborowicz, Markwitz, 2012; Lepiarz, 2010). Hormonal changes that affect perceived emotions are present from conception up to several months after birth (Kristensen, Simonsen, Trillingsgaard, Pontoppidan, Kronborg, 2018). Many women need the emotional, informational or economic support of those in their immediate environment during this period to cope with their new situation. Social support is one of the main factors influencing perinatal mental health of women (Zhang S. et al., 2020; Ginja et al., 2018; Feeley, Bell, Hayton, Zelkowitz, Carrier, 2016; Glass, Simon, Andersson, 2016). The early postnatal period is a special time when it is not uncommon for mothers to struggle with childcare difficulties, feelings of insecurity and lowered mood (Kristensen et al., 2018; Barkin, Wisner, 2013). The mother’s positive emotional state promotes adequate contact with her child in the first days after birth and helps her accept her new life situation (Yuksel, Bayrakci, 2019; Shah, Gee, Theall, 2014). During the post-partum period in the life of a woman saddled with a new social role and the new responsibilities that come with it, it is very important to find within herself and use specific skills that meet the expectations and individual needs not only of the woman, but also of her newborn child and those around her. It is very common for a woman to have household duties such as cleaning, cooking and shopping in addition to caring for a newborn child. This requires the ability to manage time and plan activities, and can sometimes be an additional stress factor. This is why it is so important to have the support and help of loved ones and to find and use one’s own potential, determining how to act in a new situation. A protective factor that motivates behaviour and the setting of new goals in life, and contributes to coping with stressful situations is a sense of self-efficacy (Juczyński, 2001). It is an important factor in helping women to go through a period of adjustment to motherhood (Shorey, Chan, Chong, He, 2015; Serçekuş, Başkale, 2016; Duprez et al., 2016).

Self-efficacy is an individual’s judgement of own competence regarding the ability to cope with tasks. It is the ability to organise and take action to overcome difficult situations. This concept is based on the social learning theory, where a person has the capacity to cope with challenges, to self-determine and to interact with the environment in which he or she lives (Izadirad, Niknami, Zareban, Hidarnia, 2017; Bandura, 1993). Individuals with a high sense of self-efficacy show high motivation to take action and continue to do so in the face of effort and difficulty. They adopt appropriate behavioural strategies and remain optimistic. People with low self-efficacy often perceive new challenges as insurmountable barriers (Izadirad et al., 2017).

The purpose of this study was to assess the level of generalised self-efficacy, the level of perceived stress and the factors influencing these levels among women during the first days after childbirth.

Material and methods

In the present study, a diagnostic survey method was applied using the author’s interview questionnaire, the Generalised Self-Efficacy Scale (GSES) using the Polish version of the tool translated by Zygfryd Juczyński and the Perceived Stress Scale PSS-10 translated by Zygfryd Juczyński and Nina Ogińska-Bulik. The Generalised Self-Efficacy Scale is a tool consisting of 10 statements that measure the strength of an individual’s general belief in their effectiveness of coping with difficult situations. The sum of all scores represents the overall self-efficacy index, which ranges from 10 to 40 points. The higher the score, the greater the sense of self-efficacy in the subject (Juczyński, 2001). The Perceived Stress Scale is used to measure stress-related feelings by examining the level of stress in a given life situation. It consists of 10 questions that refer to the subjective perception of recent events and one’s own coping strategies. In response to the questions, the respondents indicated how often they thought in the given way by writing the corresponding number. The total score was equal to the overall index of perceived stress, ranging from 0 to 40 points. The higher the score, the greater the perceived stress (Juczyński, Ogińska-Bulik, 2009).

The author’s interview questionnaire included questions on socio-demographics, on the history of pregnancy and childbirth, as well as on the support of the immediate environment in caring for the newborn, and the domestic duties awaiting the woman when she returns home. The respondents were also asked about the occurrence of positive and negative feelings related to childbirth and self-assessment of childcare skills.

The study was carried out in two maternity wards of Kraków’s hospitals after permission was obtained from the directors and heads of the institutions. Completed questionnaires were received from 110 women who filled them out during the first five days after delivery following informed consent. The women surveyed were informed of the voluntary nature and anonymity of the research.

The statistical analysis used descriptive statistics, Spearman’s rho, and the Chi-squared test, supplemented by contingency tables. The strength of dependence is shown through Cramér’s phi. A box plot chart was also used to present the distribution of statistical characteristics. IBM SPSS Statistics and Microsoft Excel were used for the calculations. The condition to demonstrate statistical significance of the calculation was p<0.05.

Test results

The age range in the female study group was 17-41 years, with the mean age of 29.19 years. The group of women aged less than 25 years accounted for 20% (N=22), the largest number, i.e. 75.5% (N=83), were aged between 25 and 35 years and the smallest group of the respondents, i.e. 4.5% (N=5), were over 35 years’ old. Ninety per cent (N=99) of the women were married, 5 per cent (N=6) were in a casual relationship and 4.5 per cent (N=5) were single. A group of 40% (N=44) of the women lived in a town of more than 20,000 inhabitants, 39.1% (N=43) lived in rural areas, while the smallest group, i.e. 20.9% (N=23), lived in a town of up to 20,000 inhabitants. The largest group of respondents had tertiary education 57.3% (N=63), 28.2% (N=31) had secondary education, 13.6% (N=15) had vocational education and the smallest group, i.e. 0.9% (N=1) of respondents, had primary education. Most, i.e. 76.4% (N=84) of the respondents were economically active, 14.5% (N=16) declared being dependent on relatives and 9.1% (N=10) were unemployed. Regarding the material situation, 2.7% (N=3) of the respondents rated it as bad, 30% (N=33) as average, 56.4 (N=62) as good and 10.9% (N=12) as very good.

A quantitative study of the level of generalised self-efficacy showed that most, i.e. 40% (N=44) of the women surveyed in the first days after delivery had a high generalised sense of self-efficacy, for 32.7% (N=36) the level of self-efficacy was average and, for 27.3% (N=30), it was low.

In contrast, the quantitative study of perceived stress levels showed that the largest group of female respondents, i.e. 65.5% (N=72), had high stress levels, 23.6% (N=26) had average stress levels and 10.9% (N=12) had low stress levels. Detailed calculations are included in Table 1.

Table 1

Descriptive statistics of Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10) and Generalised Self-Efficacy Scale (GSES) scores

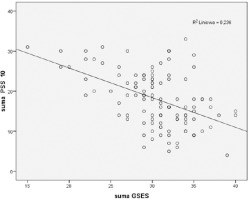

Statistical tests showed a significant relationship between the level of perceived stress and the level of generalised self-efficacy (p<0.001) among women during the first days after childbirth. The higher the level of generalised self-efficacy, the lower the level of perceived stress, while the lower the level of generalised self-efficacy, the higher the level of perceived stress among the female respondents. A dependence of moderate strength. The results are shown in Table 2 and Figure 1.

Table 2

Relationship between Generalized Self-Efficacy and Stress Level among women in the early post-partum period – Spear-man’s rank correlation

| suma_PSS_10 | total GSES | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spearman’s rho | Total PSS-10 | Correlation coefficient | 1.000 | -0.451 |

| Bilateral p-value | <0.001 | |||

| N | 110 | 110 | ||

| Total GSES | Correlation coefficient | -0.451 | 1.000 | |

| Bilateral p-value | <0.001 | |||

| N | 110 | 110 | ||

Figure 1

Relationship between Generalized Self-Efficacy Level and Stress Level among women in the early post-partum period – Spearman’s rank correlation chart

The analysis showed that the fact of being married (Chi2=30.148; df=4; p<0.001; φ=0.524) has an impact on the sense of self-efficacy as well as having a tertiary education (Chi2=22.992; df=6; p=0.001, φ=0.457), being dependent on family and being unemployed(Chi2=12.667; df=4; p=0.013, φ=0.339). The level of generalised self-efficacy is also influenced by the material situation (Chi2=29.548; df=6; p<0.001; φ=0,518). Respondents were also asked about the details of their most recent pregnancy. It turned out the fact that a pregnancy was planned or the fact that the pregnancy was a surprise for some women significantly affected their levels of generalised self-efficacy (Chi2=14.386; df:2; p=0.001; φ=0,362). Difficulties in carrying the pregnancy to the full term and the type of delivery had no statistically significant association with self-efficacy levels. Interestingly, statistical analysis showed that there were correlations between women’s levels of generalised self-efficacy and whether the baby was born after at least 37 weeks of pregnancy or prematurely (Chi2=11.435; df=2; p=0.003; φ=0.322).

There was no correlation between the marital status, the financial profile of the respondents, their employment, whether the pregnancy was planned, the type of birth and the week of pregnancy in which the child was born and the level of stress experienced (p>0.05). However, it has been shown that its level in the first days after birth was dependent on education (Chi 2=15.726; df=6; p=0.015; φ=0.378) and a history of difficulties in carrying a pregnancy to its full term (Chi 2=6.473; df=2; p=0.039; φ=0.243).

The women surveyed were also asked about their subjective assessment of their skills in caring for, recognising the needs of and keeping their child safe. Scores for self-assessment of child care skills (Chi 2=27.380; df=6; p<0.001; φ=0.499) and ensuring child safety (Chi 2=29.097; df=6; p<0.001; φ= 0.514) correlated with the level of generalised sense of self-efficacy at a significantly high level. No correlation was found between the subjective assessment in recognising the child’s needs and the generalised self-efficacy scale score. The same was true for the results of the perceived stress scale, as it was shown that the subjective assessment in recognising the child’s needs is not linked to the perceived stress score. Significant dependencies were demonstrated between the ability to care for the child (Chi 2=13.296; df=6; p=0.039; φ= 0.348) and the ability to keep the child safe (Chi 2=13.645; df=6; p=0.034; φ=0.352) and the generalised self-efficacy score.

Respondents were also asked what activities they could count on to be helped with when they returned home. Respondents’ beliefs about family helping with childcare, cleaning and shopping after their return home with women’s levels of generalised self-efficacy showed statistically significant relationships, as shown in Table 3. The level of stress experienced depends on whether the women believe that will be able to rely on help with shopping and getting up to take care of the baby at night when they return home. These and other relationships are shown in Table 4.

Table 3

Relationships between belief that family support is available after return from hospital and scores on the Generalised Self-Efficacy Scale among women in the early postnatal period

Table 4

Relationships between belief that family support is available after return from hospital and scores on the Perceived Stress Scale among women in the early postnatal period

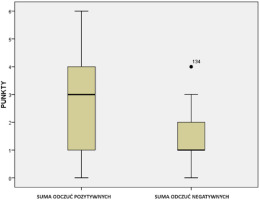

In addition, female respondents were asked about the occurrence of negative feelings related to their childbirth experience. An analysis of women’s perceptions of their last birth showed that 33.6% (N=37) of women perceived their birth as the most beautiful moment of their lives, 57.3% (N=63) of women associated it with the presence and support of their partner, and 26.4% (N=29) of women felt an inner mobilisation and confidence in their ability to cope during the birth. Just over half of the women surveyed, i.e. 54.5% (N=60), remembered childbirth as the time of waiting for the baby to arrive and 50.9% (N=56) associate the moment with support and help from staff. Indescribable joy and emotion was felt by 40.9% (N=45) of the women. When analysing negative feelings during childbirth, as many as 60% (N=66) of the women were concerned whether the baby would be born healthy, 42.7% (N=47) of the women remembered pain and suffering, 22.7% (N=25) were afraid that they would not be able to cope, while only 3.6% (N=4) of the women felt lonely during childbirth. None of the respondents felt misunderstood by the staff. In order to be able to assess the existence of a relationship between the intensity of negative and positive feelings, the results of the declaration of feelings were categorised by percentage and divided into groups: 0%-40% – low intensity of feelings, 41%-60% – medium intensity, 61%-100% – high intensity of feelings. There was a statistically significant difference in the perception of positive and negative feelings related to the last birth (p<0.001). A positive perception of the last birth is significantly more prevalent than the negative perception for the whole group of respondents, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2

Box plot showing the prevalence of positive and negative feelings among women in the early postnatal period

There was no statistically significant relationship between the levels of perceived stress and the occurrence of both positive and negative feelings (p>0.05). However, a relationship was found between Generalised Self-Efficacy Scale scores and the occurrence of negative feelings related to childbirth (Chi 2=16.485; df=4; p=0.002; φ=0.387).

Discussion

It is often assumed that women are naturally prepared, both physically and mentally, to have and nurture offspring. However, the birth of a child is increasingly perceived as a special period that requires the activation of one’s inner resources and skills required to cope with difficult situations. There are several key factors influencing women’s comfort and well-being during this special time, i.e. the first days after childbirth. Many reports demonstrate that the support received from the partner, family and friends is an important factor positively influencing a woman’s psychological well-being (Ginja et al., 2018; Zakeri, DashtBozorgi, 2018; Giurgescu, Templin, 2015), reducing the risk of post-partum depression (Zhang S. et al., 2020; Ginja et al., 2018; Feeley et al., 2016; Jonsdottir et al., 2019; Vaezi, Soojoodi, Banihashemi, Nojomi, 2019; Zhang, Y., Jin, 2016; Brazeau, Reisz, Jacobvitz, George, 2018). Furthermore, it has been found that the larger one’s social network, the lower the likelihood of post-partum depression (Jonsdottir et al., 2019; Vaezi, 2019), and the more support women receive from their partners, the lower the reported anxiety and the less frequent the depressive states despite the occurring stress (Razurel, Kaiser, Antonietti, Epiney, & Sellenet, 2017). Reports are also presented as in the study by Leonard et al., which showed that, when social support decreases over the course of the postnatal period, women’s stress levels increase (Leonard, Evans, Kjerulff, Downs, 2020). It is worth mentioning that relatives giving women material and emotional support such as time, love, trust, material assistance and encouragement to care for the child can positively affect the mother’s mental and physical state and consequently help strengthen the woman’s sense of competence for her new role (Razurel et al., 2017; Sedigheh, Keramat, 2016), which improves her sense of self-efficacy (Zheng, Morrell, Watts, 2018; Alinejad-Naeini, Razavi, Sohrabi, HeidariBeni, 2021). Research highlights the interdependence of social support, sense of psychological and functional well-being and self-efficacy (Fathi, MohammadAlizadeh-Charandabi, Mirghafourvand, 2018; Ginja et al., 2018). These reports are also corroborated by our own research, which shows that the level of self-efficacy and the level of perceived stress in women in the first days after childbirth is influenced by the belief that their partner will help them with some chores at home. Zheng, Morell and Watts further elaborate in their study proving that women who were not supported by their partners demonstrated lower levels of self-efficacy (Zheng, Morrell, Watts, 2018). Sedigheh and Keramat who conducted their study focusing on further post-partum, also confirm the effect of social support on mothers’ self-efficacy levels 6 and 12 weeks post-partum (Sedigheh, Keramat, 2016). In contrast, other authors have highlighted the fact that the level of social support and self-efficacy are influenced by a close association with a better quality of health behaviour in the post-prenatal period of mothers (Izadirad et al., 2017; Schwartz et al.,2015). However, it is not just the support itself but also the woman’s satisfaction in receiving it that plays an important role. Research shows that women rely on their partners and parents for support after childbirth, and rate this type of support as most highly valued (Razurel et al., 2017; Sedigheh, Keramat, 2016; Alinejad-Naeini, Razavi, Sohrabi, Heidari-Beni, 2021).

The studies by Tanpradit and Kaewkiattikun as well as by Büssing at al. have offered new insights, showing stress as an inherent component, independent of even the strength of the support received from loved ones. They addressed difficult situations where a woman gives birth prematurely (Tanpradit, Kaewkiattikun, 2020) or has a child who requires intensive medical supervision (Büssing, Waßermann, Hvidt, Längler, Thiel, 2018). Similar correlations regarding stress levels could not be found in our research. However, the week of the child’s birth was significantly associated with the women’s generalised self-efficacy score. In addition, both our research and the findings of a number of authors are in favour of the statement that self-efficacy is a key element that influences well-being, experienced emotions and readiness to take on the responsibilities awaiting a young mother (Fathi et al., 2018; Ginja et al., 2018; Zheng, X. et al., 2018; AlinejadNaeini et al., 2021; Chang, Schaffir, Brown, Wegener, 2019). However, the author of the Polish version of the tool for measuring generalised self-efficacy, Zygfryd Juczyński, pointed out that a high level of generalised self-efficacy alone is not sufficient when a person has deficiencies in relevant instrumental skills (Juczyński, 2001). This author’s research seems to support this statement by demonstrating a relationship between the impact of generalised self-efficacy and stress levels with women’s self-assessment of their ability to care for their children and keep them safe. A similar relationship has been observed by Pakseresht and Pourshaban and by Jia et al., who demonstrated a higher score on the breastfeeding self-efficacy scale in multiparous women compared to nulliparous women in whom the score was significantly lower(Pakseresht, Pourshaban, 2017; Jia, Ji, Wu, Wang, Wu, 2020). Similar results were obtained by the authors, who used tools measuring maternal self-efficacy and parent self-efficacy in their study (Zheng, X. et al., 2018; Botha, Helminen, Kaunonen, Lubbe, Joronen, 2020). This may be explained by the greater experience of multiparous women in breastfeeding and families in caring for their newborn (Yuksel, Bayrakci, 2019; Helminen et al., 2020) . The above results suggest the importance of family education and the huge role of different types of maternal support during this special period (Vaezi, 2019) and that there is a need for an early implementation of interventions aimed at strengthening the mothers’ sense of self-efficacy, which can significantly reduce postnatal stress and prevent mood disorders and depression in women during the postnatal period(Law et al., 2019).

It appears that certain sociodemographic factors are related to self-efficacy and levels of perceived stress in women in the first days after childbirth. In particular, studies on the impact of education are often presented, demonstrating that the higher the education of perinatal women, the higher their sense of self-efficacy (Zheng, X. et al., 2018; Jia et al. 2020; Küçükoğlu, Celebioglu, Coskun, 2014). Our own research confirmed the impact of education on levels of self-efficacy as well as perceived stress. Zheng X. and colleagues explain this relationship more broadly by the fact that women with higher education are accustomed to learning and seeking new knowledge, which may also help them find motivation to seek out and learn about topics related to newborn care during pregnancy and the post-partum period(Zheng, X. et al., 2018). Interestingly, reports to the contrary also exist, as in a study by Yap and associates in which women with higher levels of education had lower self-efficacy scale scores than those with primary and secondary education (Yap, Nasir, Tan, Lau, 2019). However, reports are consistent on the topic of the impact of economic status on levels of self-efficacy. According to the authors, the higher the economic status, the higher the level of self-efficacy (Fathi et al., 2018; Zheng, X. et al., 2018; Pakseresht, Pourshaban, 2017; Küçükoğlu, 2014). As to the nature of the work and occupation, different studies seem to pay attention to different details. Some of them highlight the fact that being unemployed affects self-efficacy (Pakseresht, Pourshaban, 2017), and such women get significantly lower self-efficacy scores than working women (Zheng, X. et al., 2018). Jia et al., on the other hand, seem to present results to the contrary by showing that unemployed mothers, as well as those working part-time, got higher scores on the self-efficacy scale than mothers in full-time employment, explaining that the women who did not work or worked part-time were able to focus more on their child, which entailed lower stress levels (Jia et al., 2020). Our own research shows an impact of employment on generalised self-efficacy, but this topic is not fully explored, and more in-depth research would be needed to resolve the dispute and assess the direction of the relationship more accurately.

The results of our research, as well as results presented in the literature, demonstrate the continuing need to search for answers and solutions in this area. This research should contribute to improving the holistic approach to women in the first days after childbirth and suggest topics for professional medical staff to pay special attention to while offering care. Early identification of whether the woman will be able to rely on support from loved ones after returning home should also be implemented and solutions and support should be suggested in order to avoid the consequences of severe stress, mood disorders and depression.

Conclusions

The higher the level of generalised self-efficacy, the lower the level of stress in women in the early postnatal period, and the higher the level of stress, the lower the level of generalised self-efficacy.

Marital status, education, material situation and employment significantly affect women’s sense of self-efficacy in the first days after childbirth.

The ability to care for the newborn and keep the baby safe has a significant impact on the level of perceived stress and self-efficacy in women in the early postnatal period.

The support offered by the immediate environment in dealing with some chores at home after a woman’s return from hospital influences the level of perceived stress and the level of generalised self-efficacy.

The level of stress among women in the first days after childbirth is not dependent on the evaluation of the birth itself in terms of positive or negative feelings.