Introduction

Running a business and effectively managing a company involves making various decisions, which should be preceded by appropriate analyses. In a dynamically changing environment, instability of legal regulations, growing competition or emerging crises, an ongoing and systematic assessment of an entity’s financial situation is particularly important, as it facilitates important operational and strategic decisions that may affect its future development (Gabrusewicz, 2014). We have seen this very clearly in recent years, when the environment in which businesses operate is characterised not only by its vibrancy, but also by the great unpredictability of the changes taking place, which affect the financial condition of the various businesses. The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 is undoubtedly an example of such a crises situation. This was such an unpredictable event that even a report commissioned by the World Economic Forum (The Global Risks Report 2020) did not include a coronavirus pandemic in the indicated groups of the world’s greatest risks and threats. This shows that the world was not prepared for such a situation. Due to its unpredictability and complex economic, social, political and even cultural consequences, the pandemic phenomenon has been called a black swan1. A black swan is a phenomenon that is considered so unlikely as to be practically impossible, whereas when it occurs it has a huge impact on reality (Antiopova, 2003; Goodell, 2020; Szczepański, 2020). The pandemic has also been compared to the economic situation during World War II (Gossling, Scott, Hall, 2020; Nicola et al., 2020).

The outbreak of the pandemic and the fight against its effects meant that businesses had to operate in new conditions, the most difficult in decades. This crisis had the greatest impact on industries that had to stop or limit their operations, including: gastronomy, tourism, hotel industry, as well as trade. In those difficult times, it was necessary to provide public support to companies with the primary aim of rescuing their liquidity. Already in the first month of the pandemic, the first Anti-Crisis Shield was launched, which later included its successive versions (from 1.0 to 6.0 and the financial shields 1.0 and 2.0 of the Polish Development Fund). An accurate assessment of the consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic, both negative and positive, and of the effectiveness of public support for businesses in the long term will probably be possible only in a few years’ time.

Undoubtedly, the functioning of enterprises in a market economy, even more so in times of crises and the associated uncertainty of future events, requires systematic analysis and evaluation of phenomena occurring, not only inside, but also outside the organisation. For the monitoring and evaluation of the financial condition of business entities, an indicator analysis is used, among other things, to assess both past, present and future activity (Sierpińska, Jachna 2004).

Forms of support for enterprises during the Covid-19 Pandemic

The beginnings of the Covid-19 pandemic took place in China, where the first cases of the illness caused by the dangerous SARS-CoV-2 virus were confirmed as early as December 2019. The town of Wuhan, where seven cases of very severe pneumonia of unknown origin were diagnosed, was the place linked to the pandemic outbreak. Very quickly, as early as 13 January 2020, the first case of disease outside China was confirmed. The situation was so dynamic that on 11 March 2020, the World Health Organisation declared a global Covid-19 pandemic (https://www.parp.gov.pl/storage/publications/pdf/kalendarium-2020_18032021-do-publ.pdf).

In Poland, the disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus was first detected on 4 March 2020 and on 7 March, the President of the Republic signed a law on solutions aimed at preventing, counteracting and combating Covid-19, as well as many other infectious diseases. The Act allowed for remote work when an employee was in quarantine, or gave the possibility to use benefits when educational institutions were closed (Act of 2 March 2020). As a result of the recommendations issued by the Chief Sanitary Inspectorate and epidemiologists, the first restrictions were introduced in Poland in the following days, including restrictions on the organisation of mass events, the closure of educational establishments and universities, the suspension of the activities of cultural centres and the closure of borders. The next phase of restrictions took place on 24 March 2020, when gatherings of people were limited to a maximum of two persons, with the exception of families, religious gatherings or workplaces, and travel and going out was limited and on 31 March all types of parks, boulevards and beaches were closed. Entrepreneurs with hairdressing, beauty, tattoo and piercing salons had to stop providing their services, and hotels could only operate if their guests were quarantined or staying there because they were doing professional work. In addition, limits were also placed on the number of people in supermarkets or markets, and only people over 65 could shop between 10 and 12 (Konat, Olejnik, 2022; https://www.medicover.pl/o-zdrowiu/pandemia-koronawirusa-na-swiecie-i-w-polsce-kalendarium). The suspension of economic processes had serious consequences related to the operation of specific economic activities. In general, the restrictive policies to prevent the spread of pandemics were strict and costly (Czech, Karpio, Wielochowski, Woźniakowski, Żebrowska-Suchodolska, 2020). Some researchers even argued that the measures taken (restrictions and limitations) made little sense and the virus itself was not that dangerous after all (Jelnov, 2020).

As the pandemic unfolded, restrictions on business activities, as well as other activities, were successively introduced and lifted, making the economic situation increasingly uncertain and the operation of economic operators unstable. Consequently, this caused an increase in the number of businesses suspending their operations, especially in the first months of the pandemic (Ligaj, Pawlos, 2021).

Since the introduction of the state of epidemic in Poland (20 March 2020), it dominated the social and economic life of Poles. The government’s first important step towards improving the economic situation was the reduction of interest rates by the Monetary Policy Council (Resolution No. 1/2020; Resolution No. 2/2020). This was primarily to relieve the burden on borrowers in hard times but was also an attempt to encourage companies and consumers to invest. Subsequently, on 18 March, the government presented a package of solutions aimed at protecting the economy against the emerging pandemic and the funds allocated for its implementation amounted to PLN 212 billion (Law of 31 March 2020). The planned support was to be as follows: cash component of the government – PLN 67 billion, liquidity component of the government – PLN 75.5 billion and liquidity package of the NBP – approx. PLN 70 billion. This package was called the anti-crisis shield and consisted of five pillars:

employee safety – PLN 30 billion,

business financing – PLN 74.2 billion,

health care – PLN 7.5 billion,

strengthening the financial system – PLN 70.3 billion,

public investment programme – PLN 30 billion.

The first pillar provided for salary subsidies in the event of a threatened job, downtime or a reduction in working hours, an additional childcare allowance for children up to the age of eight, as well as aid for self-employed persons on a contract for work or a contract of mandate (80% of the minimum wage). The second pillar focused on business financing and provided for, among other things: a non-refundable loan for companies that maintain permanent employment, an automatic working capital loan and the Polish Development Fund’s Capital for Security and Growth programme. The third pillar was related to health care, its aim was to support the health service in connection with the fight against the coronavirus, including the creation of new information channels in health care and the construction of medical infrastructure. The fourth pillar consisted of two packages. The regulatory package of the Financial Supervision Committee (FSC) and the Ministry of Finance (MoF) concerned the reduction of capital buffers or recommendations of the Financial Stability Committee and the reduction of capital or liquidity requirements of banks. The second package, the NBP liquidity package, focused on maintaining liquidity in the banking sector. The fifth pillar of the shield was linked to public investment. The action of the Public Investment Fund was to include spending on, among other things, infrastructure, the modernisation of schools and hospitals, as well as digitalisation (Barczyk, Urbanowicz, 2021).

Three weeks after the possibility of using the first anti-crisis shield, the government reported that 1.500.000 applications for support had been submitted, and it was possible to cover 900.000 jobs with the Anti-Crisis Shield programme aimed at protecting jobs. The self-employed received downtime allowances totalling PLN 250.000. In addition, one million companies applied for exemption from Social Security contributions, PLN 820 million was paid to protect jobs and 170,000 employees were to receive salary subsidies (https://www.gov.pl/web/materiały).

The Financial Shield, which was announced on 8 April 2020, presented a new form of action – the “Anit-Crisis Shield Assistance Programme”. The funds allocated for this purpose amounted to more than PLN 100 billion. Micro-companies were to receive approx. PLN 25 billion, small and medium-sized companies approx. PLN 50 billion and large companies PLN 25 billion. Subsidy limits were also set:

micro-companies – up to PLN 324,000 for 3 years,

small and medium-sized companies – up to PLN 3.5 million for 3 years,

large companies – individual arrangements.

A non-refundable subsidy of up to 75% after 12 months was also specified. A condition that had to be fulfilled was the need to continue activities and maintain stable employment levels (https://pfrsa.pl/tarcza-finansowa-pfr/tarcza-finansowa-pfr-10.html#mmsp; https://www.gov.pl/web/premier/premier-uruchamiamy-tarcze-finansowa-dla-firm).

The Regulation on granting aid from financial instruments under the 2014-2020 Operational Programmes, which took effect from 16 April 2020 (Regulation 2020), also proved to be a great support for entrepreneurs. It provided the possibility to use various types of loans, guarantees and warranties not only for investment purposes, but also, for example, for day-to-day operations if the businesses found themselves in a difficult situation due to the pandemic. The funds made available amounted to more than PLN 3.5 billion. In addition, the Bank of Credit Guarantees launched the Liquidity Guarantee Fund, which was available regardless of the industry and size of the company, and gave the possibility to use guarantees at lending banks if these had entered into cooperation agreements with BGK. The lowest guarantee amount was PLN 3.5 million, while the maximum value oscillated at PLN 200 million. This money could cover up to 80% of the loan value (https://www.funduszeeuropejskie.gov.pl/strony/wiadomosci/antykryzysowe-wsparcie-z-funduszy-europejskich-juz-obowiazuje/).

Shield 4.0, introduced by the Act of 19 June 2020 (Official Journal 2020, item 1086), concerned the possibility of using support in the form of interest rate subsidies on bank loans for companies that found themselves in a difficult situation, affected by the pandemic, and the simplified procedure for approval of an arrangement in connection with the occurrence of Covid-19.

On July 16, the President of the Republic of Poland signed the Act on the Polish Tourist Voucher (Act of 15 July 2020), guaranteeing that each child under 18 years of age would receive a subsidy of PLN 500 to be used for holidays or winter breaks, and PLN 1.000 for children with disabilities. This was aimed at Polish families, but it was also very important for the tourism industry, whose economic situation was in a very difficult condition due to the restrictions introduced.

The next anti-crisis shields, i.e. Shield 5.0 and Shield 6.0, known as industry-specific shields, provided support for selected industries. The first one allowed to benefit from a temporary exemption from the payment of social security contributions (for July, August and September) and an additional downtime allowance. While the other provided assistance in the form of an exemption from social security contributions for November 2020, a one-off additional downtime allowance, a subsidy of up to PLN 5,000 for micro and small entrepreneurs and the suspension of the market fee in 2021 (https://krd.pl/dokumenty-dodatkowe/tarczaantykryzysowa).

On 15 January 2021, the call for applications in connection with the launch of the PFR 2.0 Financial Shield began. Among other things, subsidies of PLN 13 billion were planned, of which PLN 6.5 billion were to be allocated to micro-entrepreneurs and another PLN 6.5 billion to small and medium-sized companies. 47 655 entities benefited from the programme and the amount of support was PLN 7.1 billion (https://pfrsa.pl/tarcza-finansowa-pfr/tarcza-finansowa-pfr-20.html).

The next shield – Shield 7.0, introduced by the Regulation of the Council of Ministers of 19 January 2021 (Regulation 2021), was an extension and expansion of the industry shield assistance. It included instruments such as an exemption from paying social security contributions for the next two months, a subsidy aimed at micro and small enterprises, job protection benefits and subsequent downtime allowances. Similar forms of support to specific industries were enabled in subsequent editions of the industry shield (Shield 8.0, Shield 9.0).

In summary, it can be said that the above- mentioned aid solutions within the framework of the Crisis Shield, covered a fairly wide range of instruments to support enterprises and undoubtedly mitigated the economic impact of the pandemic crisis.

Material and methods

The purpose of the study is an attempt to assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the financial condition of non-financial enterprises in Poland. As part of the main objective, an indicator analysis was carried out of the ability of the surveyed entities to pay their liabilities on time, the level of profitability, the degree of indebtedness and the efficiency of operations. The subject of the research were non-financial enterprises with accounting records and obliged to prepare quarterly reports on revenue, costs and financial result, with 50 or more employees (medium-sized and large enterprises). The research period covered 2018-2022. The main source of financial information used to achieve the aim of the study was data from the Central Statistical Office collected in the Local Data Bank.

Selected classic indicators of financial liquidity, profitability, debt and operating efficiency (turnover cycle indicators in days) were used to assess the financial situation of non-financial enterprises in Poland (Gabrusewicz 2014; Pomykalska, Pomykalski, 2017). The selection of indicators depended primarily on the availability of data in the CSO Local Data Bank for 2018-2022. It should be noted that data on the financial performance of non-financial enterprises in Poland, collected by the CSO, are presented in accordance with the Accounting Act as at the end of the period.

Analysis and assessment of the financial situ- ation of non-financial enterprises in Poland 2018-2022

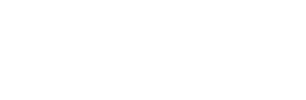

Figure 1 shows the size of the group of companies analysed between 2018 and 2022. It was found that in the examined period the number of economic entities keeping accounting books employing 50 or more employees was at a fairly stable level. In the first two years of the pandemic, there was a visible decline, while in 2022 there was an increase in the number of entities by 102 compared to the previous year, i.e. by 0.5%.

Figure 1

Number of companies analysed between 2018 and 2022

Source: Own elaboration based on CSO data – Local Data Bank.

In the surveyed group of companies between 2018 and 2022, the share of entities that made a profit was as follows: 80.6%, 81.8%, 80.4%, 84.4%, 83.1% (https://bdl.stat.gov.pl/bdl/dane/podgrup/tablica, 20.06.2023). As can be seen, the fewest entities with a positive financial result were in 2020, the first year of the pandemic, while the largest number was in 2021. This may indicate that the forms of assistance made available to companies had a positive effect.

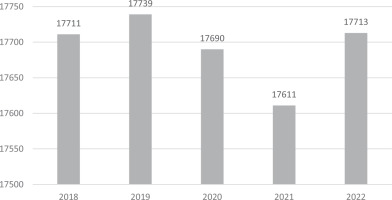

Figure 2 presents the development of the liquidity ratios of the companies analysed between 2018 and 2022.

Chart 2

Liquidity ratios of the analysed companies in 2018-2022

Source: Own elaboration based on CSO data – Local Data Bank.

The current ratio, calculated as the ratio of cur- rent assets to current liabilities, ranged from 1.45 in 2018-2019 to 1.56 in 2022. Its optimal level indica- ted most often in the literature is 1.2-2.0, according to some authors 1.5-2.0 (Gołębiewski, Gryciuk, Tłaczała, Wiśniewski, 2016) and therefore it can be considered that the surveyed entities should not have problems with current liquidity. It was found that an increase in the ability of companies to pay their debts on time was evident from 2020 onwards. This was due to a greater increase in current assets compared to the increase in current liabilities. Analysing the qu- ick ratio, it was found that the companies were able to cover their current liabilities with current assets less inventories, indicating their high financial security. This indicator oscillated around one and exceeded 1 between 2020 and 2022. The last of the liquidity ratios, the immediate liquidity ratio, indicates the extent to which the surveyed companies were able to settle their current liabilities with the assets with the highest level of liquidity, i.e. cash. By 2021, there was an upward trend in this indicator, with a slight decre- ase in 2022. In general, it should be emphasised that the surveyed group of companies was characterised by a high level of immediate liquidity, as the ratio was above 0.35 throughout the surveyed period, meaning that more than 35% of short-term liabilities could be settled immediately with cash held. The high level of immediate liquidity in 2020 and 2021 was caused by the fact that enterprises refrained from investing free cash due to the high uncertainty of their func- tioning in the future caused by the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic.

Looking at the dynamics of liquidity, it can be concluded that the aid from the crisis shields helped to improve their liquidity. However, it was not specified what the situation was like in enterprises divided into industries and to what extent the support received allowed individual entities to survive the difficult period of the pandemic.

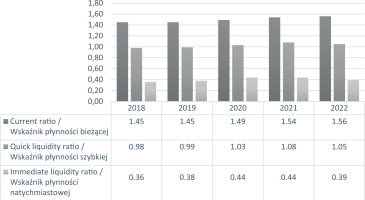

The efficiency of the business can be assessed by analysing the profitability indicators (Figure 3). Profitability analysis makes it possible to verify the extent to which a company is able to generate profit from its assets and equity, as well as its sales (Borodin et al., 2021). The return on sales (ROS) ratio, which is the ratio of net profit to sales revenue, ranged from 3.7 to 5.8 in the surveyed companies, indicating that the companies were characterised by efficiency in their core operating activities. The highest return on sales was in 2021, while the lowest was in the first year of the pandemic, when both sales revenue and profits fell.

Figure 3

Profitability ratios of the companies analysed between 2018 and 2022 (%)

Source: Own elaboration based on CSO data – Local Data Bank.

The next indicator analysed, the gross return on sales ratio, illustrates the relationship of the financial result on sales to net sales revenue. It showed a uniform upward trend over the period under review (from 4.6 to 6.0), which should be viewed positively. In contrast, in the case of the return on net turnover ratio (net profit to total income), a decrease in its level compared to the previous year was observed in 2020 and 2022, while an increase was observed in the other periods. In 2021, the ratio increased by more than 58%, driven by a significant increase in the financial result (by more than 90%) compared to total revenue.

The net return on current assets between 2018 and 2022 was between 10.2 and 15.9, meaning that each zloty of current assets generated a net profit of 10 to approximately 16 groszy. The highest efficiency in the use of current assets was recorded in 2021 and the lowest the year before.

In summary, the highest profitability of the surveyed group of companies was recorded in 2021, the second year of the Covid-19 pandemic, due to a record increase of the financial result mainly due to the falling costs and rising subsidies. However, it should be noted that the situation in this respect varied by sector.

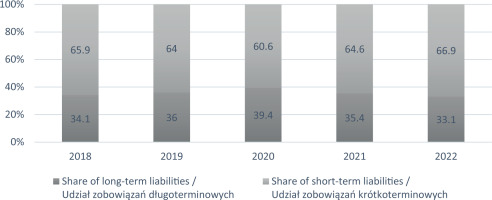

Due to certain limitations resulting from the lack of sufficient data on the analysed group of companies (lack of information on the value of equity and total assets), indebtedness was assessed on the basis of: indicators of the share of long-term and short-term liabilities in total liabilities, indicators of the dynamics of liabilities and the degree of financing of current assets with external capital. Figure 4 shows the ratio of long-term liabilities and the ratio of short- term liabilities to total liabilities. Short-term liabilities accounted for a significantly higher share (between 60 and 70 per cent) of the external capital financing of the activities of the surveyed group of companies. An increase in their importance was observed from 2021 onwards. This was due to the increasing share of short-term trade payables in total liabilities.

Figure 4

Share of long-term and short-term liabilities in total liabilities in the companies analysed in 2018-2022 (%)

Source: Own elaboration based on CSO data – Local Data Bank.

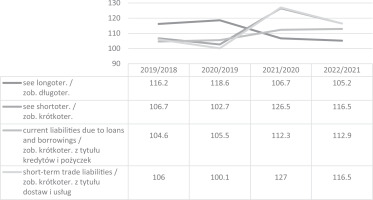

Observing changes in individual items of external capital over time, a growing trend is visible (Figure 5). The highest rate of growth in long-term liabilities was recorded in 2020, while in the case of short-term liabilities in 2021. A significant increase in the value of short-term borrowed capital was observed in the last two years analysed, which may indicate that after the first year of the pandemic and the difficulties resulting from production and sales stoppages, there was a recovery, which was associated with an increase in the value of short-term liabilities.

Figure 5

Indicators of the dynamics of liabilities in the companies under review from 2018 to 2022 (previous year=100%)

Source: Own elaboration based on CSO data – Local Data Bank.

Figure 6 shows the degree of financing of current assets of the analysed enterprises with external capital.

Figure 6

The degree of financing of current assets of the analysed enterprises with external capital in 2018-2022 (%)

Source: Own elaboration based on CSO data – Local Data Bank.

In the group of companies analysed, the ratio was above 100% in all years except 2022. Furthermore, by 2020, an increase in this measure was evident, indicating decreasing financial stability. In contrast, in the following years, the degree of financing of current assets with external capital decreased and, as a result, reached 95.8% in 2022, meaning that equity capital fully financed fixed assets and a small part of current assets. This is a desirable situation, demonstrating the financial independence of companies.

The operating efficiency of the analysed group of business entities was determined on the basis of the following indicators: inventory turnover cycle in days, accounts receivable payment cycle in days, accounts payable payment cycle in days and cash conversion cycle (Table 1).

Table 1

Performance indicators of the analysed companies from 2018 to 2022 (in days)

During the period under review, there was a slight increase in the inventory turnover time from 36 days to 40 days, which may have been due to business constraints in certain industries. Another indicator in this group, i.e. the accounts receivable payment cycle indicator, was quite stable, as it was 43-44 days, except in 2022, when it dropped to 39 days. A relatively short period of receivables collection with a decreasing tendency indicates proper management of this asset. In this group of companies, liabilities were settled within 83-93 days. The longest cycle was recorded in 2021, while the shortest was one year later. The prolongation of debt maturities in the first two years of the pandemic was probably due to the high degree of uncertainty and the need to adapt to the new business environment, especially for the industries most affected by the pandemic crisis. The reported low cash conversion cycle indicates that the surveyed companies received payment for products or goods sold even before paying off their trade liabilities, which is a favourable situation. It should be noted, however, that the occurrence of a negative conversion cycle, with the exception of the retail industry, can be a negative phenomenon, indicating excessive involvement of current liabilities in financing operations. The highest negative result occurred in 2021 (-10 days).

Conclusion

The crisis caused by the Covid-19 pandemic has undoubtedly affected, to varying degrees, not only the economic activity of companies and their financial situation, but also social life. It will probably take years for economies to return to pre-pandemic levels, although it cannot be ignored that the lockdown situation and various restrictions have also given impetus to many changes, created conditions for additional growth in certain industries, and revolutionised sales and the labour market. The Covid-19 pandemic, although it had many negative consequences, also spurred technological change. Entrepreneurs had to rely on remote work, automation and digitalisation to find their way in the new environment. Furthermore, in some industries, innovation has proved essential to survive.

On the basis of the analyses conducted, it was concluded that the surveyed group of non- financial enterprises (medium and large) in the period 2018-2022 did not have problems in settling their obligations on time, as evidenced by liquidity ratios that were within the recommended safe ranges. Furthermore, their business was profitable, which should be viewed positively. After the first year of the pandemic, where, on average, the financial performance of companies declined, there was a near doubling of profits in 2021 due to, among other things, the various forms of support launched under the Crisis Shield. In recent years, the average level of financing of current assets with external capital has also decreased. Perhaps this is indicative of the growing financial security of businesses. In addition, there was a relatively short cycle for the turnover of inventories, receivables and payables during the period under review, indicating the overall efficiency of the businesses.

Generally, based on the analyses carried out, it was not found that the Covid-19 pandemic had a significant negative impact on the current financial results of the analysed group of enterprises. On the other hand, it can be noted that the second year of the pandemic (2021) was relatively successful for Polish entrepreneurs, as both the liquidity and profitability of companies on average were higher than before the pandemic, which could mean that, firstly, companies had already become somewhat accustomed to the difficult situation, and, secondly, the government support in the form of anti-crisis shields, during this most difficult period, had brought the desired effect. Of course, it would be important to verify the extent to which the aid received under the crisis shields granted in connection with the COVID-19 pandemic contributed to improving the liquidity and overall financial situation of operators on an industry-specific basis and thus enabled them to survive the difficult period of the pandemic. This indicates the future direction of research.

In 2022, the financial situation of the entities surveyed, in some areas, deteriorated compared to the previous year. It can be assumed that, in an environment of increasingly lenient epidemiological policies, the coronavirus itself was no longer as much of a problem as the fact that companies were facing employment challenges, the problem of rising commodity prices, disrupted supply chains and changes in the tax system. In addition, there were the economic effects of the war in Ukraine, increasing inflationary pressures, as well as rapidly rising interest rates. Undoubtedly, the last few years have been a time of vigorous and unpredictable changes, the social, political, cultural as well as financial consequences of which may only become apparent in a few years’ time. Thus, it will be very important to systematically analyse the financial condition of enterprises in future periods.