Introduction

Throughout history, humanity has witnessed some of its darkest moments, marked by wars, killings, and conflicts that have shaped the world. These events, though painful and tragic, have left indelible marks on societies, influencing political landscapes, cultural identities, and collective memories. From ancient wars that determined the rise and fall of great civilizations to modern-day conflicts that continue to plague certain regions, the world has remained in a perpetual cycle of violence and resilience (Talukdar, Dutta, 2020; Vesco et al., 2025; Verwimp et al., 2019).

One of the earliest recorded large-scale wars in history was the Peloponnesian War, which took place between Athens and Sparta in the 5th century BCE (Knox, 1973). This conflict, marked by strategic battles and immense bloodshed, demonstrated the consequences of power struggles and political alliances gone awry. Moving forward to the Middle Ages, the Crusades, religious wars sanctioned by the Latin Church, resulted in thousands of deaths in the name of faith (Nelson, 2007; Theron, Oliver, 2018), reinforcing the idea that ideological differences could serve as catalysts for conflict. The 20th century stands out as the bloodiest era in human history (Ferguson, 2006). The First World War (1914-1918) was a devastating global conflict that led to the deaths of over 16 million people, both military personnel and civilians (Tibbitts, 2021). The introduction of trench warfare and chemical weapons turned the battlefields of Europe into sites of unimaginable horror (Hewitson, 2016; Fitzgerald, 2008; Vilches et al., 2016; Schmidt, 2017). Just two decades later, World War II (1939-1945) erupted, surpassing its predecessor in scale and brutality (Bocco, 2024; Kesternich et al., 2014). The Holocaust, orchestrated by Nazi Germany, led to the systematic extermination of six million Jews (Sweeney, 2012; Russell, 2018; Berenbaum, 1981), while the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945 showcased the destructive power of nuclear weapons (Dower, 1995; Ali, Jassim, 2024; Vaughn, 2021). World War II alone claimed an estimated 70-85 million lives (Roberts, 2021; Tran, 2014; Vergun, 2020), forever altering the geopolitical landscape.

Post-World War II conflicts continued to shape the world in violent ways. The Korean War (1950-1953), the Vietnam War (1955-1975), and the Cold War-era proxy battles between the United States and the Soviet Union kept global tensions high. Meanwhile, genocides such as those in Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge regime and in Rwanda in 1994 demonstrated the horrifying extent of human cruelty (Williams, Jessee, 2024; Williams, 2021; Burnet, 2015; Rieder and Elbert, 2013; Banyanga et al., 2017). More recently, ongoing conflicts in the Middle East, such as the wars in Iraq and Syria, have resulted in millions of casualties and widespread displacement (Petrini, Alajlouni, 2024; Ferris, Kirisci, 2016; Keseljevic, Spruk, 2023; Hashim, 2007; Khorram-Manesh et al., 2021). Terrorist attacks, such as the 9/11 attacks in the United States, have also marked contemporary history with fear and destruction (Kellner, 2004; Neria et al., 2012; Nielsen, 2008). These global events not only changed national borders and political systems but also deeply affected the psyches of individuals and communities (Murthy, Lakshminarayana, 2006; Javed, 2024; Yasegnal, 2022; Matanov et al., 2013). The memories of war, suffering, and atrocities are preserved in history books, memorials, and museums, serving as constant reminders of what humanity is capable of, both in terms of cruelty and resilience.

In the Philippines, a history of colonization and conflict has significantly influenced cultural and historical narratives. The country was under Spanish rule for 333 years (Ocay, 2010; Elizalde, 2022; Skrabania, 2021), American governance for 48 years (Colalijo, 2023; Iyer, Mauer, 2009; Masanga, 2021), and Japanese occupation for three years (Cheng Chua, 2019; Saniel, 1969; Gosiengfiao, 1966). As a result, culture and heritage in the Philippines cannot be separated from war and conflict, as these events have largely shaped its historical identity. In fact, many of the country’s museums are dedicated to preserving memories of war, struggle, and resistance. Spanish colonization, which began in 1565, imposed profound political, economic, and cultural transformations on the archipelago (Rafael, 2018; Pearson, 1969). The introduction of Christianity (Stosic et al., 2016; Skrabania, 2020), the encomienda system (Anderson, 1976; Elizalde, 2022), and forced labor led to widespread suffering (Rafael, 2018). Several uprisings, including the Dagohoy Rebellion and the Ilocos Revolt, underscored Filipino resistance to Spanish rule (Aparece, 2013; Santiago, 2015; Antonio, Ancheta, 2014; Pilapil, 1965). This colonial period ultimately gave rise to revolutionary movements, particularly the Katipunan, which sought independence through armed struggle. The Philippine Revolution of 1896 marked a turning point, with figures like Andrés Bonifacio, Emilio Aguinaldo leading the charge for liberation (Gonzales, 2017; Guerrero et al., 2003; Marshall, 2023).

Following Spain’s defeat in the Spanish-American War, the Philippines was ceded to the United States under the Treaty of Paris in 1898 (Bautista, 2008). However, Filipino aspirations for independence were met with military opposition, leading to the Philippine-American War (1899-1902) (Holm, 2013). This conflict, characterized by brutal counterinsurgency tactics, resulted in massive casualties, particularly among Filipino civilians. American governance introduced modern education and infrastructure but was also marked by policies that suppressed nationalist movements (Francisco, 2015; Maca, Morris, 2012). World War II brought another period of turmoil, as Japan invaded the Philippines in 1941 (Soriano, 1948). The occupation was marked by widespread atrocities, including the Bataan Death March, in which thousands of Filipino and American prisoners of war perished (Murphy, 2011; Jose, 2001). The eventual liberation of the Philippines in 1945 left the country in ruins, necessitating extensive rebuilding efforts.

As a result of these historical events, many museums in the Philippines are either former homes of national heroes who fought against colonizers or structures converted or built into museums showcasing artifacts and narratives of significant struggles. The Bataan World War II Museum, for instance, commemorates the hardships and sacrifices of soldiers and civilians during the infamous Bataan Death March. The Veterans Memorial Museum highlights the contributions of Filipino veterans in various conflicts, particularly World War II. The Emilio Aguinaldo Shrine, the former residence of the first Philippine president, marks the site where Philippine independence was declared in 1898. Similarly, the Dr. José Rizal Shrine honors the life and legacy of the national hero, whose execution by Spanish colonial authorities played a pivotal role in igniting the Philippine Revolution. More recent historical events are also preserved in museums, such as the Martial Law Museum, which documents the human rights violations and political repression during Ferdinand Marcos’s administration from 1972 to 1986. While it currently exists as a digital museum, a physical structure is under development to further educate the public about this period in Philippine history.

The prevalence of conflict-themed museums raises important questions about their impact on contemporary Filipino society. A key area of inquiry is how these historical representations shape present-day attitudes, perceptions, and national consciousness. On one hand, these narratives serve as educational tools, enabling individuals to learn from past conflicts to promote peace and prevent history from repeating itself. On the other hand, exposure to these historical accounts may reinforce collective trauma, evoke pain, or even cultivate animosity toward groups associated with past conflicts. Research on historical memory suggests that the way societies remember and interpret past conflicts significantly influences behavior. Pierre Nora’s (1989) concept of sites of memory highlights the role of physical spaces, such as museums, in shaping collective identity. Similarly, Maurice Halbwachs’ theory of collective memory (1980; 1992) argues that societies reconstruct historical narratives to align with contemporary needs and perspectives. In this context, war museums, including those that narrate other forms of conflicts, play a crucial role in shaping national consciousness, influencing how individuals process historical trauma and reconcile with the past.

Research on war memorialization has shown varying effects on national identity and intergroup relations. Some studies suggest that commemorative spaces foster national unity and encourage reflection on peace (Carbone, 2021; Jamil et al., 2025; Nyema, Frank, 2018). Others argue that the portrayal of past conflicts can reinforce divisions, particularly when narratives emphasize victim-hood or external aggression (Carbone, 2023; Maguire, 2017; Psaltis et al., 2017; Jankowitz, 2018). In the case of the Philippines, the depiction of colonial and wartime experiences may contribute to either reconciliation or lingering resentment, depending on how historical accounts are framed and interpreted by museum visitors. Hence, this study seeks to examine how war- and conflict-centered historical narratives in Philippine museums influence public consciousness. It aims to determine whether these representations promote learning and reconciliation or if they reinforce division and resentment. By analyzing how individuals engage with these historical accounts, this research will contribute to a deeper understanding of the role that historical memory plays in shaping societal perspectives. The findings of this study are expected to have implications for museum curation, historical education, and public policy. If war museums are found to promote reconciliation and learning, their educational potential can be further harnessed to foster a more informed and reflective society. However, if they are found to incite division or resentment, it may be necessary to reconsider how historical narratives are presented to ensure a balanced and constructive approach to the past. By examining these dynamics, this research contributes to ongoing discussions on the power of historical memory and its influence on contemporary social and political realities.

Objective

This study aims to examine the role of museums in the Philippines that showcase narratives of war, conflict, and suffering in shaping public perception and emotional responses. Specifically, it seeks to determine whether these museums serve as instruments of healing and reconciliation or if they perpetuate pain, fostering resentment and hostility toward the people, races, and countries involved in these historical events. Furthermore, the study intends to explore the broader implications of these emotional and psychological effects on peace-building efforts in the country, particularly in influencing societal norms and behaviors. It also aims to assess whether individuals’ responses to these museums vary based on demographic factors such as age, sexuality, educational attainment, and social classification. Additionally, the research will investigate whether museum visitors perceive these institutions as representations of historical truth or if they maintain their pre-existing beliefs despite their visit. Through this analysis, the study seeks to contribute to discussions on the role of historical narratives in shaping national identity, collective memory, and reconciliation efforts in Philippine society.

Methodology

This study employed a descriptive-concurrent mixed methods design to comprehensively analyze the effects of war and conflict-centered museums on visitors’ perceptions, emotions, and attitudes. The research integrates both quantitative and qualitative approaches to provide a holistic understanding of the subject matter. A total of 381 Filipino museum visitors participated as respondents, with 95 participants from each of the Philippine Veterans Museum, Bataan World War II Museum, and the Philippine Army Museum Library and Archives, and 96 participants who have seen the Virtual Martial Law Museum. The study’s sampling strategy ensures diverse representation across museums focusing on war, suffering, and historical conflicts.

Data collection was conducted through a combination of face-to-face and online surveys and interviews. The survey gathered quantitative data regarding participants’ perceptions and emotional responses to historical representations in these museums. The mean scores of survey responses, based on a 4-point Likert scale, were computed and analyzed using Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) to identify significant differences in responses based on demographic factors such as age, sexuality, educational attainment, and social classification. In addition to the quantitative component, qualitative data were collected through interviews to gain deeper insights into visitors’ experiences and interpretations of the museum exhibits. Thematic analysis was performed to identify recurring themes and patterns in participants’ narratives, shedding light on how these historical representations contribute to healing, reconciliation, or the perpetuation of historical pain.

Table 1

Research Locale

The locations for this study were chosen based on their perceived relevance to one of the bloodiest periods in Philippine war history, World War II. The Virtual Martial Law Museum was also considered, as events relating to Martial Law in the country from 1972 to 1986 have been identified by Filipinos as the most significant historical events (Liu, Gastardo-Conaco, 2011).

Ethical Considerations

This study adhered to all ethical research principles. Participation was entirely voluntary, and no respondent was coerced into answering the survey. The data collected were used exclusively for this research, ensuring the confidentiality and anonymity of all responses. Respondents’ names were not recorded, and their responses remained private. Before taking part in the survey, they were fully informed about the study’s objectives, scope, and the identity of the researcher. They were explicitly asked whether they were willing to provide information on their age, sexuality, educational attainment, average monthly income, and perceptions towards museums. Participation was conditional upon their consent, and they were not required to answer the questionnaire if they chose not to. Additionally, respondents were informed beforehand that they would not receive any form of compensation for participating in the study. The researcher, hereby, confirm that this study adhered strictly to Republic Act 10173, also known as the Data Privacy Act of 2012 in the Philippines, as well as to the Declaration of Helsinki of 1964 on informed consent, ensuring that respondents’ privacy rights were not compromised. The ethical guidelines established by the Directorate General for Research and Innovation of the European Commission, specifically those outlined in the document “Ethics in Social Sciences and Humanities,” were also taken into account. Lastly, as a signatory of the San Francisco Declaration on Research Assessment (DORA) and a supporter of the ICMJE Recommendations, the researcher ensures that this research from the conduct to the publication phase did not commit any malpractices. By following these ethical standards, the researcher guarantees that the study was conducted with integrity, prioritizing the rights and welfare of all participants.

Results and Discussion

Do museums in the Philippines, particularly those that depict stories of war, conflict, and suffering, help heal wounds and foster reconciliation, or do they perpetuate pain and fuel hatred or anger?

Table 2

Visitor Resentment Toward Individuals and Groups Featured in Conflict-Themed Museum Exhibits

| Subject | Mean | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Personalities involved in conflict events | 3.23 | Moderate Pain |

| Institutions/Countries/Races involved in conflict events | 2.98 | Moderate Pain |

| Composite Mean | 3.10 | Moderate Pain |

These data indicate that people tend to harbor hatred or anger toward those involved in the sufferings inflicted on Filipinos in the past. However, beyond specific individuals, it was revealed that people often generalize, directing anger and hatred toward entire races or countries involved, such as the Spanish, Americans, and Japanese. The Americans, on the other hand, after colonizing the Philippines, later liberated the country, which explains the long-standing relationship between the Philippines and the USA. Spain and Japan, however, are less liked by Filipinos, as their colonization periods were marked by hardship and suffering. Specifically, the data showed that, rather than healing wounds, museums about conflict, wars, killings, or suffering tend to perpetuate pain.

In the study of Cosse and Funke (2022), it was revealed that people affected by wars often generalize the individuals and nations involved. For instance, there have been incidents of hate crimes committed against Russians and those perceived as Russians due to the war between Russia and Ukraine, even when these individuals are not directly involved. In fact, as cited in the same article, on March 30, 2022, Michelle Bachelet, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, noted that “a rise in Russophobia has been observed in a number of countries.” This phenomenon has also been observed on social media platforms such as TikTok (Fillies et al., 2025), further suggesting that people really tend to generalize nationalities, particularly when the subject involves the suffering and pain inflicted on others. Meanwhile, in reference to World War II, Rozin et al. (2014) found that while it cannot be generalized, there is a lasting dislike towards Germans expressed by American and Czech Holocaust survivors, as well as Jewish-Americas, even decades after the war. This dislike extends even to Germans born after World War II. Similarly to the current case of Filipinos in relation to past conflicts, as well as to what Ukraine is going through amidst Russian aggression, this suggests that reflecting on the past, especially when it involves events that caused significant suffering, can result in resentment and deep-seated animosity toward the groups perceived as responsible. Moreover, this animosity can persist across generations, affecting even those born long after the conflict. It is also important to note that Germany’s aggression leading to WWII resulted in the suffering and deaths of millions of people from various nationalities, including Belarusians, Estonians, Latvians, Lithuanians, Poles, Russians, Ukrainians, and Yugoslavs. Aside from being killed in battles, many were forced into hard labor as part of an aggressive campaign to conquer and establish colonies in Eastern Europe (Popowycz, 2022), which may indicate a lingering resentment toward Germans in these countries to this day.

Clearly, this means that how history is remembered and portrayed, whether through museums, education, or media, can reinforce division and perpetuate negative sentiments toward entire groups or nations.

Table 2 also points out that the level of hatred is not extreme. Participants in the current study were given options to choose the level of impact on them, with the highest being “strongly agree,” interpreted as extreme pain. The consolidated responses showed that most participants simply agreed, indicating that while museums do perpetuate pain, leading to anger or hatred against the people and institutions involved, the intensity is not at an extreme level. This suggests that feelings and perspectives may be changeable through adjustments in how these stories are told and how the events are presented.

Some Impacts of Societal Animosity on Peace-Building, as Reflected in Current Norms and Behaviors

The data shown in Table 2 relate to how Filipinos react to fellow Filipinos who support people or are related to people involved in the sufferings of the past, such as the Martial Law period from 1972 to 1981, which is considered a dark time in Philippine history. In fact, the Martial Law era and the 1986 People Power Revolution that resulted in a change of leadership are two of the most important historical events for Filipinos, while Spanish colonization, Philippine independence, and Japanese colonization during WWII rank third, fourth, and fifth, respectively (Liu, Gastardo-Conaco, 2011). As a result, the degree of hatred many people feel towards those primarily involved during Martial Law and their relatives is generally high, to the point that even public figures who have shown support for them are being canceled. For instance, the family of former President Marcos, who declared Martial Law in 1972, faces a lot of scrutiny and aggression for being active in politics today. In fact, public figures who supported the presidential campaign of now-President Bongbong Marcos Jr. (PBBM), the son, were greatly canceled, such as the Gonzaga Sisters, who are famous for being singers and movie stars. They were slammed on Twitter by several people after being spotted at then-presidential candidate Bongbong Marcos’ headquarters (Ulnagan et al., 2022). Following this, many people called for the public to stop patronizing their work, such as, but not limited to, their YouTube channel and movies (de Leon, 2021). Thus, the data presented could be one reason why cancel culture continues to thrive in the Philippines and why elections are always polarized. People tend to hate those involved in past horrors, affecting even those who are related to or simply favor them, rather than allowing reconciliation and fostering peace-building.

Another case involves the Lumads. The Lumads, a collective term for non-Muslim Indigenous peoples in Mindanao, inhabit remote, resource-rich areas such as forests, mountains, and ancestral domains. These areas are also known hotspots for the New People’s Army (NPA), a Maoist guerrilla group founded in 1969 that seeks to overthrow the Philippine government through protracted armed struggle. Due to the NPA’s continued presence and influence in these areas, people and groups, such as the Lumads, who express the same grievances and reside in the same geographical locations, are treated differently. They are frequently red-tagged, or accused of being communist rebels or sympathizers, even in the absence of concrete evidence (Alvarez, 2023). Despite the Lumads’ repeated denials of affiliation with the NPA and public declarations of neutrality, state forces and some sectors of society continue to perceive them as insurgent-aligned (Perez, 2019). This perception has fueled military harassment, forced evacuations, surveillance, arrests, and even killings of Lumad leaders, educators, and community members. This clearly establishes a default association of indigeneity with rebellion, creating a dangerous environment where simply asserting ancestral land rights or operating alternative schools is interpreted as subversive.

Significant differences in the effects of museums on visitors when grouped by demographic profile

Table 3

Does the effect on people differ in terms of age, sexuality, educational attainment, and social classification?

| Demographic Information | Subject | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Age | Influence of museums towards reconciliation and resentment | P < 0.05 |

| Educational Attainment | P < 0.05 | |

| Sexuality | P > 0.05 | |

| Social Classification | P > 0.05 |

When grouped by age, the results revealed that the younger generation, particularly Gen Z, tends to absorb most of the pain perpetuated by these dark stories of the past. The youngest generation tends to harbor more hatred, while millennials show the least tendency toward negative emotions and display more openness to peace-building. Gen X and Baby Boomers, on the other hand, fall in the middle but still feel more pain than peace toward such historical narratives. This is potentially due to their actual experiences or the experiences of their parents or relatives during those times, as they were old enough to have witnessed what really happened and felt what it was like. In terms of educational attainment, the data closely mirrors those based on age, suggesting that people’s perspectives, when differentiated by age, are influenced by their level of education. However, there is a slight difference among bachelor’s, master’s, and Ph.D. holders, as the pain tends to increase as the degree level progresses. This is understandable, especially among undergraduate students, as it could mean that a lack of in-depth understanding of the narratives leads to a more negative perspective toward the people and institutions involved.

In regard to sexuality and social classification, the data revealed no significant difference. This means that regardless of sex and social class, people tend to have the same perspective toward historical narratives on conflicts. Apart from the suffering endured due to the killings during WWII, Filipino women suffered sexually as ‘comfort women’, a term used for women who were exploited for sexual pleasure by the Japanese during the war (Yoshiaki, 2000; Borromeo, 2010). Literature suggests that between 1932 and 1945, thousands of women were rounded up and imprisoned in ‘comfort stations’ brothels where they were detained for a certain period, stripped of their rights, and forced to engage in sexual activity with Japanese military personnel. This, however, makes the results of the current study surprising. It is mind-boggling why female respondents did not express a significantly higher degree of resentment compared to male respondents, given what their social group went through during previous wars. In the study by Litchfield, et al. (2024) on the 1998-1999 Kosovo war and its influence on current political participation, it was determined that the experience of conflict and its influence on political participation has distinctions between men and women. For instance, displacement was associated with more voting among women, but not men, and with more demonstrations by men, but weaker or no effects for women. Meanwhile, death and injury were associated with higher political party membership for men but not for women. This could indicate that women are more civil when confronting their reflections on past conflicts in their country, compared to men who display more aggressive actions. This potentially explains why no significant difference was found when comparing the effects of war and conflict narratives between male and female respondents in the Philippines, despite women’s experiences during WWII, beyond just death. This is further supported by Toussaint and Webb (2007), who explain that women tend to be more empathetic than men, which potentially influences their perspective toward perpetrators of wars and conflicts in the past.

Are museums trusted?

Table 4

Do museum visitors perceive museums as representations of historical truth, or do most retain their own beliefs after visiting?

| Response | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | 239 | 63% |

| No | 142 | 37% |

The results show that most tourists believe museums accurately represent the country’s heritage, indicating that they are perceived as sources of historical truth. However, it is important to note that 37% believe otherwise, meaning that 4 out of every 10 Filipinos may question the accuracy of historical narratives presented in these institutions. This suggests that many Filipinos may have biases influenced by stories from other sources, including those passed down from family, friends, and society. Similarly, a report by the American Alliance of Museums (2021) found that American museumgoers regard museums as highly trustworthy, second only to friends and family, ranking significantly higher in trustworthiness than researchers, scientists, non-government organizations, news organizations, the government, corporations, and social media.

Primary reasons why some people contest historical narratives presented in institutions such as museums

Theme 1: History is influenced by Politics

Filipinos believe that history is influenced by politics. Over the past few decades, the political landscape in the Philippines has consistently intertwined with historical narratives, leading Filipinos to perceive a strong connection between the two. A clear manifestation of this is cancel culture during elections, where the country’s polarization is evident due to differing interpretations of historical events. Previous studies support this sentiment. For instance, Gray (2015) argued that museums not only have a political dimension but are inherently political. This is evident in Russia, where the Kremlin has extensively manipulated historical events as a tool for foreign interference to achieve strategic objectives (Arribas et al., 2023). A similar case has been observed in Zimbabwean museums and archival collections, where institutions face significant challenges in balancing political and power pressures while maintaining professional and ethical standards (Sibanda and Chiripanhura, 2024).

Theme 2: Differing Opinions Between “Official” Historical Narratives and Those Told by Elders.

Filipinos have observed inconsistencies between official historical narratives and the accounts shared by their elders, particularly regarding recent historical events such as the Martial Law era. Given the strong family ties in Filipino culture and the prevailing belief that politics influences history, many Filipinos find personal stories from relatives more credible than the narratives presented by government institutions and heritage organizations. The report by the American Alliance of Museums (2021) supports this perspective, revealing that while museums are regarded as highly trustworthy, people tend to place even greater trust in their family and friends. This suggests that when historical narratives differ, individuals are more inclined to believe those they have personal connections with rather than institutions perceived to be influenced by the government.

Implications of Museums’ Influence on the Public for Post-Conflict Peacebuilding

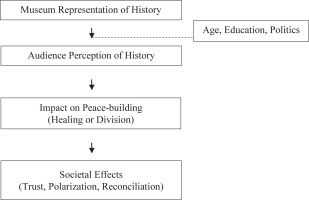

This study has paved the way for the conceptualization of the Historical Perception and Societal Impact Model. This model follows a logical sequence, beginning with Historical Narrative Representation. It starts with museums presenting historical events (Gunay, 2012; Carlsson, 2024), which, as suggested by the current study, may either align with personal family histories or reflect official state-driven accounts. This initial distinction influences how individuals process information and reacts emotionally. Consequently, the Perception of Historical Events varies among individuals. As revealed, factors such as age, education, and political beliefs shape how people interpret historical narratives. For instance, some may feel a strong emotional connection to personal histories, while others may become skeptical or even disillusioned by state-controlled narratives. Thus, perception plays a crucial role in determining how history is internalized.

As a result, the role of Museums as Catalysts for Peace-Building becomes evident. Museums, depending on how historical narratives are received by the public, may either contribute to the healing of wounds caused by historical suffering or exacerbate pain. Either way, this leads to the Impact on Post-Conflict Society. Museums that successfully foster trust in institutions and encourage empathy help bridge divides and contribute to societal healing. Conversely, those that reinforce historical polarization may deepen social divisions and hinder reconciliation. Thus, the way history is presented in museums has profound implications for peace and societal cohesion. This model, which can guide scholars in developing a more detailed framework, is intended to provide a generalized insight into how museums influence the way people accept what took place in the past, which in turn shapes their perceptions of the people, institutions, and countries involved. It is argued that such perceptions may either enable reconciliation and promote peace or reinforce hatred rooted in past suffering.

Conclusion

This study provides a novel contribution to understanding how historical narratives shape public perceptions, particularly in the context of political and social divisions in the Philippines. While previous research has examined historical consciousness and political influences on memory, this study uniquely highlights how generational differences, educational background, and sources of historical knowledge impact the way Filipinos interpret the past. Notably, the findings underscore that younger generations, especially Gen Z, tend to internalize historical pain more intensely, leading to heightened animosity. Meanwhile, Millennials exhibit a greater openness to peace-building, and older generations, despite their lived experiences or direct familial connections to past conflicts, remain divided in their emotional responses.

A key argument presented in this study is the significant influence of politics on historical narratives. Filipinos widely believe that history is shaped by political interests, reinforcing the polarization observed during elections and public discourse. This aligns with global findings on how governments and institutions frame historical events to support specific agendas. Furthermore, the study reveals a deep-seated skepticism toward institutionalized historical accounts, as many Filipinos place greater trust in stories passed down by relatives who experienced these events firsthand. This skepticism is reflected in how museums, despite being considered credible, are still perceived by a considerable portion of the population as potentially influenced by political biases. The disconnect between official historical narratives and personal accounts fuels ongoing societal divisions and resistance to reconciliation efforts.

These findings are potentially substantial for peace-building efforts in the country. The persistence of historical animosity, particularly among younger generations, suggests that mere historical documentation is insufficient in fostering national unity. Instead, there is a need for a more inclusive and reconciliatory approach in presenting historical events, one that acknowledges multiple perspectives and actively engages the public in dialogue. Museums, educational institutions, and policymakers must recognize that history is not just about preserving facts but about shaping collective memory in a way that promotes understanding rather than division. Addressing these challenges requires an effort to bridge the gap between official historical narratives and personal testimonies, fostering a culture where critical thinking and empathy play a central role in historical interpretation.

This study highlights the intricate relationship between history, politics, and collective memory. It emphasizes the need for more nuanced discussions on historical events to move beyond antagonism and towards a society that values both truth and reconciliation. If history continues to be a battleground for political influence, then efforts toward peace-building and national unity will remain elusive. Thus, fostering a more balanced and participatory approach in how historical narratives are presented is essential in shaping a more cohesive and informed society.

Recommendations

Based on the findings of this study, the promotion of a more balanced and inclusive approach to historical narratives and their impact on societal perspectives is recommended. To do this, it is essential to enhance historical education by integrating multiperspectivity, ensuring that students are exposed to both official accounts and personal narratives. Schools and universities should collaborate with historians, educators, and affected communities to provide a more inclusive and accurate representation of the past. Museums should also adopt a more interactive and transparent approach by incorporating oral histories and disclosing their sources and methodologies to build public trust. Additionally, media literacy programs must be strengthened to equip Filipinos with critical thinking skills, enabling them to analyze historical narratives objectively and resist politically motivated distortions. It is also essential that open dialogue and reconciliation efforts are encouraged through platforms that allow different generations to share their views and experiences, fostering national unity rather than division. Community-based historical documentation initiatives should also be developed to preserve diverse perspectives, ensuring that history is not solely dictated by political authorities. Moreover, politicians and public figures must be mindful of their rhetoric, promoting unity instead of polarization and ensuring that historical institutions remain independent from political interference. By implementing these measures, society can move toward a more informed, reconciliatory, and objective understanding of history, ultimately reducing division and fostering national solidarity.