The need for digital accessibility

The development of information and communication technologies (ICT) has resulted in an increasing part of our social and professional life being carried out online. ICT solutions are also entering more and more deeply into the functioning of Polish public administration. There are at least several reasons for this. E-Administration provides easy access to documents and matters, allows them to be “de-located” (there is no need to appear in person at the office) and makes it possible to deal with a “bundle” of matters related to the handling of an entire life or business event (Janowski, 2009). It is not insignificant to reduce the direct involvement of administrative staff in dealing with individual customers and, in the long term, to rationalise and reduce operating costs. Additionally, the COVID 19 pandemic has resulted in a much larger group of citizens and entrepreneurs becoming convinced that contact with the administration using ICT is not only safe from the point of view of health, but also enables the efficient handling of necessary matters. This has forced the public administration in Poland to carry out numerous adaptation activities that enabled electronic handling of matters. Mainly at the level of accepting digital applications and providing digital responses. Internal case handling processes in offices are still primarily paper-based.

Unfortunately, the increase in the use of ICT in public administration is also increasing the level of the digital divide. The term “digital divide” refers to the separation of those who have access to digital information and communication technologies and those who do not use them (Riggins, Dewan, 2005). Although it is generally acknowledged that poverty is the main exclusionary factor, digital exclusion should be treated like communication exclusion (lack of access to public transport, lack of access to road networks), demographic exclusion (the problem of digital exclusion mainly affects people of working age or older) or civilisational exclusion (lack of access to education, science, work or health care). If we add disability to the above exclusions, the importance of digital exclusion increases even more. This is why it is so important to reduce technical and formal barriers to the use of ICT by all those concerned - regardless of their digital competences, state of health or other psycho-physical limitations. We often forget that there are some people who, despite wanting to, are unable to navigate the Internet without any problems. This is due, among other things, to the various limitations faced by these people. Digital accessibility is intended to ensure that no one is excluded and content is tailored to different audiences (Kolbus, 2023).

The Internet has been created so that virtually anyone can use it, regardless of hardware, software, language, location, skills. However, in order for this to work, the websites, web applications, mobile applications, as well as the software that enables the creation and management of these solutions, must comply with certain rules. One of these principles is “digital accessibility, i.e. making digital solutions so understandable and simple that most people can use them without additional customisation. At the same time, digital accessibility supports those users who benefit from special additional solutions” (www.gov.pl,2022) .

Digital accessibility of e-services appears to be particularly important in the area of health e-services and social welfare e-services. Their users, in a proportionally higher part than in other e-services, are people at risk of digital exclusion due to health reasons (reduced fitness, disability), competence (age, education) and territorial reasons (size of place of residence, part of the country with lower than average income levels) (www.gov.pl,2022).

Digital accessibility of public entities

The requirements for digital accessibility of public entities are mainly contained in the contents of the Act of 4 April 2019 on digital accessibility of websites and mobile applications of public entities (Journal of Laws 2019, item 848) and the Annex to the Act. Without analysing the entire content of the document in detail, we can consider that the public entity (including social welfare bodies) should organise its work according to the four principles indicated in the Annex to the Act.

These principles are described in an accessible way in the literature:

perceivability – the property of a website or mobile application that enables it to be perceived by the user through the sense of hearing, sight or touch;

functionality – the property of a website or mobile application that enables the user to take advantage of all the functions it offers;

comprehensibility – the property of a website or mobile application that enables the user of those websites and applications to understand the content and presentation;

compatibility – the property of a website or mobile application that enables the website or application to work with as many programs as possible, including tools and programs that assist people with disabilities (Tylińska, Jahl, 2019).

In practice, this means that websites and web applications should be developed in accordance with the WCAG 2.1 standard at level AA, the 2019 set of guidelines for digital and information and communication accessibility of websites and mobile applications, which is an extension of the requirements contained in the previous version of the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG 2.0) of 2012 – which, among other things, was referred to in the Regulation of the Council of Ministers (Journal of Laws 2012, item 526).

In the practice of the “ordinary” user, this may mean using, for example:

fonts with a simple typeface,

appropriate – not too small – font size,

high contrast between text and background,

friendly and understandable language,

alternative descriptions for graphic elements,

unambiguous descriptions for links and buttons,

intuitive and easy-to-fill forms,

easy-to-navigate websites and applications (Mroczkowska, Cieślak, 2023).

In addition, it is a statutory requirement to publish an accessibility declaration indicating the extent to which accessibility requirements are/are not met. These requirements are related to the rigour of sanctions. The following are subject to a fine:

unjustified and persistent lack of action to ensure digital accessibility,

lack of or failure to provide an accessibility declaration,

lack of corrective actions recommended as a result of the accessibility check.

The amount of the fine is up to PLN 10,000 for failure to ensure digital accessibility or failure to declare accessibility, and up to PLN 5,000 in the case of lack of improvement demonstrated in two consecutive inspections (Journal of Laws 2019, Item 848).

Another piece of legislation regulating the accessibility obligations of public entities is the Act of 19 July 2019 on Ensuring Accessibility for Persons with Special Needs (Journal of Laws 2019, item 1696). According to Articles 1 and 2 of the Accessibility Act, the accessibility of public entities is to be ensured in three areas through architectural accessibility, information and communication accessibility and digital accessibility. Each public entity is obliged to provide accessibility in the listed areas to the extent specified by the minimum requirements referred to in Article 6 of the Accessibility Act and the Digital Accessibility Act.

The Act indicates that ensuring accessibility for people with special needs is to be a factor to be taken into account when planning activities. Public entities should take active steps to remove and prevent barriers. And all this through the application of universal design or rational improvement (Mroczkowska, Cieślak, 2023). In addition, the Act introduces the obligation to appoint an accessibility coordinator (plenipotentiary) (Article 14).

Study on the accessibility of social welfare entities

After the end of the vacatio legis for the websites of public entities resulting from the Regulation of the Council of Ministers (Journal of Laws 2012, item 526), a physical survey of websites provided by selected public entities involved in the organisation and direct provision of public assistance in Poland was conducted in 2015. The analysis of the results shows that, with few exceptions, the websites of the surveyed public entities (central and local government administration) were not prepared in accordance with the requirements of the Regulation of the Council of Ministers of 12 April 2012. Unfortunately, this also means that a significant part of them not only does not support digital inclusion, but on the contrary deepens social exclusion (Nowak, 2015).

Following the change in the legal environment in the area of digital accessibility resulting from the entry into force of the Act of 4 April 2019. (Journal of Laws 2019, item 848), the Act of 19 July 2019 (Journal of Laws 2019, item 1696) and the experience of the COVID 19 pandemic, it would seem that public administration has reduced the exclusionary shortcomings of the e-services provided. Unfortunately, as the results of the research (Nowak, Zajdel, Jęcek, Salachna, 2023) show, apart from the positive changes resulting from the development of information technology and the observance of formal organisational requirements (declaration of accessibility, appointment of an accessibility officer), at least at the level of local government administration, no significant improvement can be seen in the area of the necessary staff competences that would allow the creation of digitally accessible content in accordance with accessibility principles.

The 2022/2023 survey examined how the requirements in the area of accessibility are being implemented by those involved in the organisation and delivery of social assistance services. A total of 346 entities (communal, municipal Social Assistance Centres (GOPS, MOPS) and District Family Assistance Centres (PCPR)) took part in the survey. However, as the statutory obligation to provide public information was not enforced by the entities surveyed, the sample must be considered random.

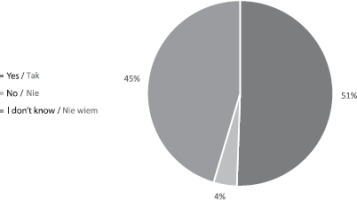

Figure 1

Number of social welfare institutions from individual voivodeships that took part in the survey

Source: own study.

The first part of the study looked at the extent to which the statutory requirements had been implemented. The Act (Journal of Laws 2019, Item 1696) requires the appointment of an accessibility officer in each public institution. Only slightly more than half of the respondents (174 out of 346) declared that they have an accessibility officer or a person who has accessibility tasks in his or her area of responsibility.

Confirmation of the relatively low level of involvement of social welfare institutions in ensuring the accessibility of their services is provided by the high percentage of respondents who did not include accessibility issues in their internal organisational procedures (179 out of 346).

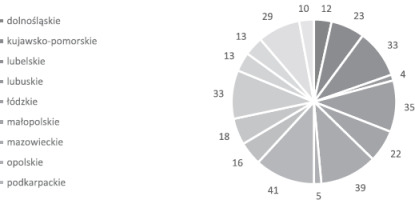

The second part of the study examined the substantive preparations of social welfare institutions for the provision of digitally available services. The vast majority of entities surveyed had trained a small proportion of their staff in digital accessibility - as many as 66% of respondents indicated training less than 10% of their team. This means that competence in the creation of digitally accessible documents and content is not widespread among the employees of the surveyed entities, despite the fact that the obligation to provide training in this area for all employees of public entities follows directly from the Act (Journal of Laws 2019, Item 1696). No significant distribution deviations were detected in the responses due to the type of entity (GOPS, MOPS, PCPR).

Figure 2

Number of staff trained to produce and share digitally accessible documents and content

Source: own study.

In the period immediately prior to the introduction of the digital accessibility obligation, the offer of training in this area was very limited. In fact, the only comprehensive (commercial) training was conducted by the “Widzialni” Foundation (www.widzialni.org).

Since 2019, the situation has changed significantly: a large training campaign for public entities was carried out by the Ministry of Digitalisation (several tens of thousands of people were trained), commercial training offers other than widzialni.org have appeared, as well as many self-help materials available online (webinars, tutorials and guides). However, while the training courses offered by the Ministry of Digitalisation and commercial training providers were usually prepared and delivered competently in terms of content and in accordance with the training principles, self-help materials often raise doubts as to their substantive quality - of the 20 analysed free “self-help materials” available online, as many as 14 do not meet digital accessibility standards. Most of the materials analysed (12) do not deal with a comprehensive explanation of the issue of ensuring digital accessibility by obliged entities, but rather with the practical implementation of selected elements of digital accessibility.

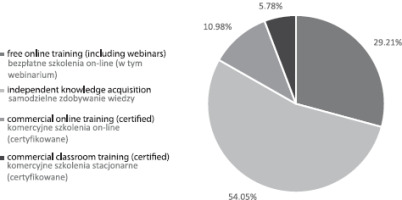

Figure 3

free online training ( including webinars) independent knowledge acquisition commercial online training (certified) commercial classroom training (certified)

Source: own research.

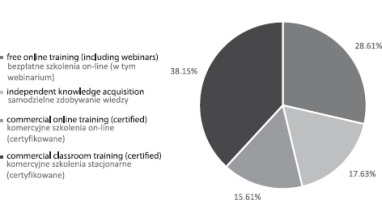

In the survey carried out, respondents clearly indicated that the form of improving competences in the field of digital accessibility was inadequate to the scale of the complexity of the issue. Dedicated training courses were indicated as the most desirable way of acquiring knowledge in the area of accessibility (82.37% of indications). Only 17.63% of respondents indicated the most commonly used form (self-study) as being adequate for improving employees’ digital accessibility skills.

Figure 4

Forms of training considered most effective in acquiring digital accessibility knowledge

Source: own survey.

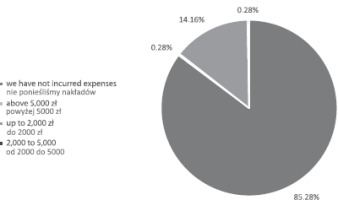

However, assuming that employees of social welfare entities, and especially their managers, act rationally, it should be recognised that the basic criterion for choosing the form of training was the financial capacity of the entities surveyed.

This is confirmed by the amount spent on digital accessibility training for employees of the surveyed entities in the year preceding the survey (2021). More than 85% of the entities surveyed (with no significant differences by the type of entity surveyed) did not spend a single zloty on this purpose.

Figure 5

Amount of expenditure incurred on staff training on digital accessibility in 2021.

Source: own study.

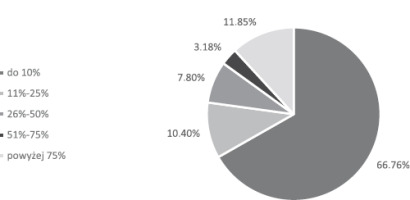

However, there is a chance that the situation regarding digital accessibility training should improve in the near future. As many as 51% of the respondents say they would like to be referred for digital accessibility training in the near future, while only 4% said they would not.

Surveys carried out in public entities at the turn of the year are burdened with many risks - closing the financial year and preparing for the new one often results in postponing other tasks, especially non-mandatory ones such as completing surveys, or even ignoring them altogether. With this in mind, we recognise that our respondents responded in a professional, reliable and credible manner even on difficult issues – if only by admitting to not fulfilling the statutory obligation to appoint an accessibility officer.

As an auxiliary study, the implementation of the WCAG 2.1 standard was checked in 70 randomly selected websites of social welfare entities (51 MOPS and GOPS websites, 19 PCPR websites). The survey was carried out using an automatic validator (www.wave.webaim.com). Source code errors, code error alerts, contrast errors and errors in shared digital content were chosen as accessibility indicators. The results of the analysis are shown in the table 1 below.

Table 1

Analysis of compliance with the WCAG 2.1 standard for selected websites

The analysis of the data collected confirms that the problem with the digital accessibility of the websites of social welfare bodies is competence-based rather than technological. More than 67% of the websites surveyed were prepared from an IT point of view very well (between 0 and 4 code errors), with an additional more than 15% at an acceptable level (between 5 and 9 code errors). This means that the IT specialists of these institutions, or the entities creating their websites under contract, have implemented the WCAG 2.1 principles in the web source code they create, or are using page generators that automatically implement these principles.

The maintenance and development of web services is slightly worse. This is evidenced by the small percentage of sites with low (14.28% from 0 to 4) or acceptable (14.28% from 5 to 9) alert levels. This means that the source code of the sites is in most cases not developed and updated. It can be assumed with a high degree of probability that this is due to the difficulties of the surveyed institutions in providing continuous IT support.

As the content of the surveyed sites fills up, their digital accessibility decreases significantly. More than 31% of the websites surveyed contain an unacceptable number of contrast errors (10 or more) and almost 73% contain a very high number of content errors (10 or more). A very strong correlation can be seen here between content errors and the number of social welfare staff referred to digital accessibility training (see Figure 2). This directly implies that the people preparing and providing digital content in the dominant part of social welfare institutions do not have sufficient competences to do so according to accessibility principles.

Conclusions of the study

Digital accessibility is one way of ensuring equal rights and opportunities for people with disabilities, which is why it is increasingly becoming a legal and ethical requirement in many countries. The goal of digital accessibility is to ensure that people with disabilities can use the same products and services as people without disabilities, thereby promoting social inclusion and equal opportunities for all people, regardless of their background and limitations (EARC, 2023).

The research carried out showed that the issue of digital accessibility in social welfare entities is not prioritised. And this on several levels:

half of the surveyed social welfare bodies implement statutory accessibility obligations (e.g. appointment of a proxy),

an even smaller group of entities (48%) have been proactive in addressing digital accessibility by including digital accessibility issues in internal rules and instructions,

there has been no widespread training of employees to build/improve their digital competences in the area of accessibility. And this is despite the many free, systemic opportunities, i.e. participation in projects and training organised by the central administration. As a result, competence in creating digitally accessible documents and content is rare. This conclusion is directly confirmed by the results of a study of the websites of selected social welfare entities: while the vast majority of these websites were prepared correctly from a programming point of view, the number and type of errors in the published content means that few meet the required accessibility standards.

In addition to a lack of commitment, the activities of social welfare entities show a lack of money (the dominance of self-education in acquiring knowledge and this despite the awareness that professional training is far more effective) and a lack of support in ensuring digital accessibility from the founding and supervising bodies, which for most of them are local government units. As confirmed by the authors of the study on digital accessibility provision by local government units: the vast majority of TSUs (more than 90% of those surveyed) comply with formal requirements, the fulfilment of which is easy to control and sanctioned by law. However, it is not possible to demonstrate from the survey that digital accessibility considerations have indeed been integrated into the standard activities of local government. A qualitative leap in the digital accessibility of administration is only possible through the implementation of an accessibility-oriented modus operandi in the operating standards of offices, and in a widespread and effective way, training of officials and the ability to create digitally accessible documents and content added to the minimum standard of digital competence required of public administration is necessary (Nowak et al., 2023).

In conclusion, it should be noted that, despite technological advances ensuring that the technical and technological requirements of digital accessibility are relatively easy to implement, the level of provision in social welfare entities can hardly be considered satisfactory. As the study of selected websites of social welfare entities showed, financial and competence barriers (ensuring full IT support and spreading competence in creating and sharing digital content) remain key.

An active society is an engaged society. As a society, we are different and we need to take this into account in various aspects of our lives – the digital ones too (Kolbus, 2023). Digital accessibility is a process in which the attitudes of creators and users of the digital world, keeping up with changes in the legal environment and the involvement of public actors at every level are equally important. Accessibility measures should also, for synergy, be planned and coordinated, both as part of the activities of individual actors and as part of joint activities.