Introduction

Security is one of the most important human needs that constitutes a fundamental, existential value, and an overriding objective of the state is to guarantee security. However, there are a number of threats in the modern world (natural, anthropogenic and hybrid threats), which due to their nature and areas of occurrence, deprive people of the opportunity to provide for this existential need (Jarmoszko, 2011). Political, economic, social, environmental or military threats are all significant challenges for state security policy. It can be assumed that military threats are the most serious of these, as war results in the destruction of the proper functioning of the state and its citizens (loss of sovereignty, death of many people, destruction of infrastructure on a massive scale, total extermination of a nation), as well as changes in geopolitical relations.

Wars have always been present in the coexistence of nations, states or international alliances. Because of their effects, it can be said that they have been and continue to be the greatest threat, the source of which is human activity directed against another human being for the purposes of sovereignty, acquisition of territory, or economic domination (Bodziany, 2010). It should be stressed that armed conflicts have always been linked to the issue of civilians fleeing from threatened areas.

The war unleashed by Russia against Ukraine on 24 February 2022 has become a source of the migration crisis in Europe. This crisis has particularly affected Poland as a country bordering Ukraine, and is unprecedented of its kind in Europe since the Second World War. However, the wave of people coming from Ukraine did not stop in Poland; some refugees moved further towards Western Europe. European countries are trying to deal with the influx of migrants into their territories. They use various migration policy tools and processes to do this. The most important of these include border protection, visa policy or rules for taking up employment by foreigners. Migration processes have been particularly dynamic in recent years and, as a result, it has become very difficult to control them accurately at the national level, which requires close international cooperation.

In the unique situation of the war on Poland’s eastern border, the decision was made to allow easy border crossing for all those fleeing the war. The statutory guarantee provides that “if a citizen of Ukraine (...), arrived legally on the territory of the Republic of Poland in the period between 24 February 2022 and the date specified in the provisions issued on the basis of paragraph 4 and declares his/her intention to stay on the territory of the Republic of Poland, his/her stay on the territory of the Republic of Poland shall be considered legal until 4 March 2024” (the Act of 12 March 2022, Journal of Laws 2023.103).

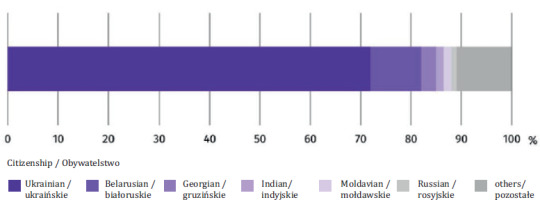

Due to the travel ban imposed by the Ukrainian government on men between the ages of 18 and 60, refugees have mainly been women with children. According to the Central Statistical Office, Ukrainians are the largest nationality group among foreigners residing in Poland, as shown in Figure 1.

Fig. 1

Foreigners working in Poland in 2022 (as at 31 December)

Source: CSO report Foreigners working in Poland in 2022.

The purpose of the study is to show the problem of refugees from Ukraine in the face of war with Russia in 2022 during the initial period of aggression: the specifics of the phenomenon, its description, identification of causes, course and conditions, and interaction with the host country (Poland).

The scope of the analysis covers the first months of hostilities, when a large wave of civilians arrived in Poland while fleeing the effects of actions taken by the Russian army, which is known as the refugee crisis.

The results of this process under specific conditions and contexts were analysed using the case study method. The data used in this study were obtained through literature and document analysis.

Population flow – the concept and types of migration

Population movement or, in other words, migration is an integral part of human functioning and part of the history of development of individuals, social groups and even entire nations. Migration (Latin: “migratio”), means “resettling”. More broadly, these are specific migrations or movements of people in order to change their place of residence or domicile for some time or permanently. According to various sources, it is assumed that approximately 3% of the world’s contemporary population migrates, which roughly translates into about 200 million people residing in a country other than their own for more than a year (Castles, Miller, 2011).

Over several tens of thousands of years, the wanderings of many generations of homo sapiens across continents have determined where humans operate on Earth. The following stages of these wanderings can be distinguished: going out of Africa to Southeast Asia, Oceania and Australia via the present-day Middle East and in another direction: from Africa to America via Siberia and Alaska (Stoła, 2018). City-states were established in antiquity, followed by empires. The medieval period saw the development of trade routes between important developing centres, as well as a time of crusades and conquests. Thanks to the great geographical discoveries, the conditions were being created for the establishment of colonies in Africa, America and Asia. This in turn resulted in the creation of the “imports” of slaves from Africa to be used as labour in the colonised areas. Subsequently, the French Revolution, the Napoleonic Wars, the Partitions of Poland, as well as the First and Second World Wars gave rise to successive great waves of migration. In turn, the bipolar division of the world after World War II undermined the migration opportunities of the population living in the then socialist countries.

There have been further waves of migration in recent years, driven by wars in Syria, Ukraine and African countries. At present, there is a renewed exodus of people from Africa to southern Europe (especially Italy). The migration of people from many poorer countries to more developed countries in order to find employment also continues unabated.

The diversity of migrations makes it possible to create a typology of this phenomenon. In terms of an area, they can be divided into external and internal. External migration refers to the movement of people between countries and can take various forms such as:

people from another country moving in permanently, i.e. immigration,

people departing permanently from one country to move to another, i.e. emigration,

returning to one’s home country after a long period of forced stay beyond its borders, e.g. for political reasons, called repatriation,

returning to one’s country after a temporary stay abroad, i.e. re-emigration,

exile, i.e. forced emigration resulting from unfavourable economic or political conditions, e.g., armed conflicts, wars, revolutions, etc. (Bożyk, 2004).

Internal migration refers to the movement of people within a country, i.e. from countryside to cities, from cities to countryside, from cities to other cities and from countryside to countryside.

Migrations are also divided based on the criterion of decision-making into:

voluntary – that is, when migrants voluntarily decide to resettle and have options in doing so,

coercive – situations in which migrants are forced to leave their place of residence, e.g. refugees (Gieorgica, 2018).

Causes of migration are another criterion for distinguishing types of migration. Causes listed here:

labour migration – motivated by the desire to seek work or increase one’s remuneration,

social migration – involves a change of residence where the reason may be, for example, marriage, • religious migration – pilgrimages to places of worship,

tourist migration – i.e. trips related to sightseeing and leisure,

health migration – related to a change of residence due to a desire to improve one’s health, e.g. going to a sanatorium,

ecological migration – i.e. a change of residence due to the state of the natural environment, e.g. leaving agglomeration centres for sparsely urbanised areas.

Migration may also be divided according to legal considerations:

legal migration – that is, staying outside one’s country with valid documents that entitle the migrant to stay in another country,

irregular migration – refers to the stay of migrants without valid documents outside the country,

unregulated residence – occurs after the document authorising legal residence has expired (Kacperska, Kacprzak, Kmieć, Król, Łukasiewicz, 2019).

The war in Ukraine and the situation of the civilian population

Since the beginning of human history, wars have had a huge impact on the formation of the world’s social order. These resulted in the creation of new states (e.g. the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics) and the simultaneous destruction of others in the economic and political sense. War, being the continuation of politics but pursued by violent means to force the opponent to do our bidding, is in essence a bloody armed struggle fought by organised armed forces (Skibiński, 1978).

In recent years, Russia has been pursuing a plan to rebuild its empire to its pre-1997 state. To this end, it waged hostilities in Chechnya in 2002, six years later in Georgia, and launched an aggression against the south-eastern territories of Ukraine in 2014. There, military action led to the creation of two internationally unrecognised republics: Lugansk and Donetsk, which remain under the aegis of Russia. The same year also saw the annexation of Crimea. This continued with the invasion of Ukraine by Russian troops, which began on 24 February 2022. Ukrainian army positions, as well as civilian facilities, were subjected to prolonged rocket fire followed by the Russians launching a ground offensive. However, Russian aggression was met with fierce resistance from all directions and did not achieve its objectives; on the contrary, a counter-offensive by Ukrainian troops allowed some Russian-occupied territory to be regained. Media reports indicate that the aggressor is suffering heavy casualties in men and equipment. In addition, the determined resistance of the Ukrainians caused the Russian army to target the civilian population. A number of war crimes occurred, of which the towns of Bucha, Mariupol or Izium have become symbols. Russian missile shelling of civilian facilities results in civilian casualties in Ukraine and causes massive damage to civilian infrastructure. Targets of attacks include residential buildings, cultural facilities, schools, shopping centres and critical infrastructure. Killings and rapes as well as abductions and forced deportations of civilians, including children, have also been reported (Waszczykowski, 2022). Humanitarian crises abound in the devastated cities as a result of shortages of food, water, electricity and heating. These actions are aimed at breaking the spirit of the Ukrainian people and forcing them to capitulate. They are also a kind of revenge by the Kremlin for Ukraine’s opposition to Russia’s imperial ideas.

Since the beginning of the Russian invasion, the Ukrainian people have shown their courage and determination to put up determined resistance to the aggressor. Despite the overwhelming superiority of the Russian army, its brutality and destruction on a massive scale, the patriotism of Ukrainians and their rage against the invaders prevail. Despite this, the aggressor’s actions resulted in a wave of refugees, primarily women and children (Eberhardt, Iwański, Konończuk, 2023).

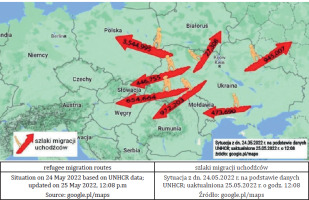

Since the first days of the attacks, a significant proportion of Ukraine’s civilian population has sought refuge outside their country. Among all the countries bordering Ukraine, it is Poland that has become the main destination for refugees from war-torn Ukraine, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Migration routes for refugees from Ukraine

Source: https://dziennikbaltycki.pl/uchodzcy-z-ukrainy-dokad-uciekaja-mapa-szlakow-migracji/ar/c1-16078399 (accessed 09.10.2023).

Ukrainian refugees as forced migration

The Russian aggression against Ukraine in 2022 had a significant impact on migration in many Central and Eastern European countries, including Poland. The influx of war refugees inevitably raises questions about the future and challenges of the presence of Ukrainian citizens in Poland. This requires decisive and conscious action on the part of public institutions. Moreover, given the scale of the influx, Poland should be seen as a new immigration country in Europe and also in a global context (Duszczyk, Kaczmarczyk, 2022). Poland and Ukraine are territorial neighbours who are also culturally close. These factors as well as the large Ukrainian diaspora make Poland a fairly obvious choice as a place to stay for those fleeing the war in Ukraine (Monitor Deloitte Report, 2022).

It is important to emphasise the difference between the phenomenon of refugees, forced by dramatic and often uncontrollable factors such as wars, persecution on the grounds of nationality, race or ethnicity, and migration resulting from a voluntary decision in search of better living conditions, education or a desire to explore the world. A refugee, in encyclopaedic terms, is a person persecuted for reasons of: political opinion, race, religion, membership of a particular social or national group in their home country, residing outside the territory of that country and unable to avail themselves of the protection afforded by that country, an additional premise being an individual’s fear of persecution, (https://encyklopedia.pwn.pl/haslo/ uchodzca;3990750.html, 27.09.2023).

Asylum seekers and those recognised as refugees fleeing from persecution find protection in international refugee law, comprising a collection of both international and regional legal instruments. In particular, the experience of World War II led to the adoption of many legal instruments for the protection of human rights. A broad definition of a refugee is found in the Geneva Convention, which states that a refugee is a person who, ‘as a result of events occurring before 1 January 1951 and owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of their nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail themselves of the protection of that country, or who, not having any nationality and being outside the country of his habitual residence as a result of similar events, is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to that country’(OJ 1991.119.515).

The granting of refugee status is another form of international protection. It can be granted to a foreigner if he or she is actually at risk of persecution in his or her country, or if there is a real risk of loss of life or health. It is important, however, that in doing so, there must be no circumstances indicating that the refugee may pose a threat to the security of the host country (e.g. being a wanted criminal).

According to Polish law, a foreigner may be granted protection on the territory of the Republic of Poland through the following mechanisms: granting refugee status, granting subsidiary protection, granting asylum, granting temporary protection (Act of 13 June 2003. Dz. U. 2003 No. 128 item 1176). According to the Office for Foreigners, 2022 has seen both an increase in the number of applications for international protection and a reduction in the length of proceedings in connection with the situation across the eastern border. Applications for international protection in Poland were submitted by 1.8 thousand Ukrainian nationals, compared to 260 applicants in 2021. The time limit for processing an application for international protection is 6 months according to the law and, in view of the special situation, has been reduced by almost 2 months (https://www.gov. pl/web/udsc/ochrona-miedzynarodowa-w-2022-r 20.06.2024).

The entry of citizens of Ukraine admitted to the territory of the Republic of Poland from the territory of Ukraine in connection with military operations conducted on the territory of Ukraine is recorded in the Border Guard’s ICT system (Act of 12 March 2022, Dz.U.2023.103). Based on the available data from the Polish-Ukrainian border on entries and exits to Poland in 2022, the dynamics of the refugee movement are shown in Figure 2 and Table 1.

Chart 2.

Dynamics of the Poland – Ukraine refugee movement as of February 2022

Source: https://oko.press/ilu-jest-uchodzcow-z-ukrainy (accessed 23.06.2024).

Table 1

Poland – Ukraine border traffic from 24 February 2022 (in thousands per month)

[i] Source: Own work based on https://oko.press/ilu-jest-uchodzcow-z-ukrainy (accessed 23.06.2024).

Three phases are observed in Poland – Ukraine border traffic. The first phase lasts from February until April. The months of February and March are marked by a very high number of refugees (2,412,000 entries into Poland and 441,000 exits). Traffic to Poland exceeded traffic to Ukraine by almost 2 million (1,971,000). Traffic was less intense in April, with the departures from Ukraine exceeding arrivals in Ukraine by only 104,000. The second phase covers the following four months (May – August). Departures of Ukrainian citizens from Poland prevailed this time (a difference of 330,000). During this phase, the departures of men who had worked in Poland and were returning to defend their country were particularly intense. The third phase covers the following four months (September–December). During this period, the number of departures from Poland and entries into Ukraine was similar. The slight prevalence (30,000) of returns to Ukraine in December may have been related to the traffic related to Christmas and New Year celebrations.

The data clearly show a significant increase in the number of Ukrainians entering Poland in the first months of the war. It amounted to more than 2 million people. This situation entails the need to take care of refugees and provide them with the best possible opportunities to function in exile.

Challenges arising from hosting refugees from Ukraine

The mass flight of the Ukrainian population required the construction of a multi-level system in which the relevant actors could take action according to their competences. Measures taken by the state administration include:

creation of reception points for refugees (in Dorohusk, Dołhobyczów, Zosin, Hrebenne, Korczowa, Medyka, Budomierz, Krościenko), which provided information on the conditions of their stay in Poland, assisted in finding accommodation, provided meals, basic medical care or the possibility to take a short rest,

establishment of information points and hotlines for refugees at voivodeship offices,

the right for refugees to stay in Poland for 18 months, including the possibility to obtain a PESEL number and a trusted profile, access to health care and social benefits (e.g. parental benefit also called 500+, Good Start, nursery subsidies, a one-off subsistence benefit of PLN 300 per person) and access to the labour market (Grabkowska, A. Pięta-Szawara, 2022).

In addition, third sector entities joined the efforts to organise humanitarian aid for refugees. They took action both on the Polish-Ukrainian border and in the interior of the country. For example, Caritas Poland launched 32 Migrant and Refugee Assistance Centres between 24 February 2022 and February 2023. They provided Ukrainian citizens with free psychological assistance, legal counselling, Polish language courses, job placement centres and play areas for children. More than 2 million meals were served during the border crisis. There were 31,000 volunteers helping Ukrainian refugees across Poland. In addition, in-kind aid was delivered to Ukraine. This included food, medicines and necessities. Caritas Poland has also initiated the Parcel for Ukraine campaign which involved sending out more than 83,000 parcels. In total, Caritas provided PLN 597,000,000 worth of aid to Ukrainians, both those residing in Poland and those who remained in their country. The community involvement of local action groups that organised themselves through social media is also worth noting. Their activities were voluntary (https://caritas.pl/ukraina/ 05.10.2023). From the very first days of the refugees’ inflow to Poland, volunteers helped at aid stations at the border, where food, clothing, blankets and sleeping bags were donated. Emergency accommodation was organised, key information was provided to confused and frightened people fleeing the war who had left behind their possessions and often fled with only their personal belongings. Spontaneous transport into the country was organised at the helpers’ expense, allowing refugees to reach their families or friends. Poles welcomed refugees into their homes to ensure that they could live in a country foreign to the newcomers.

Refugees have their unique concerns and needs. Having fled war-torn areas, they still have to face challenges in their new location. These include:

cultural challenges – unfamiliar language in the new place of residence, different religion, differences in customs and cultural norms;

economic challenges – unemployment, wage and skills gap in employment;

infrastructure challenges – availability of housing and rental homes, urban and regional problems, transport exclusion;

social challenges – lack of social networks, separation from families, reduced participation in social and political life, less access to education and integration for young people (Baszczak, Wincewicz, Zyzik, 2023).

In order for Ukrainian migrants fleeing the war to find favourable living conditions in Poland, the following courses of action have been taken:

Building a positive atmosphere around migrants – implementing an inclusive aid model. In contrast to the traditional model of setting up refugee camps, the Polish government has implemented a solution that provided programmes and laws passed in Poland based on the following assumptions: – to accept any Ukrainian citizen fleeing the war, regardless of whether Poland would be a destination or transit country for them, – integrating Ukrainian refugees into Polish social life, which in practice meant the prospect of gainful employment, the possibility for Ukrainian children to receive education, and the possibility for them to associate and take part in cultural life, taking into account their own national traditions.

Benefits – those arriving in Poland from Ukraine could count on the following forms of monetary assistance:

In addition, the Polish state has provided many other forms of assistance, including in kind, to people arriving from Ukraine:

psychological help;

24-hour catering;

cleaning products;

medicines;

places of refuge;

transport to designated accommodation;

free use of public transport.

Education, upbringing and care of children in foster care and in educational establishments

The right to conduct business activity – in this respect, the Polish legislation made no difference between Polish and Ukrainian citizens

Medical care – Ukrainian citizens were granted the right to healthcare benefits that Polish citizens with statutory compulsory or voluntary health insurance could count on (Monitor Deloitte Report, 2022).

As a result of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the European international refugee rights protection system has encountered a phenomenon of forced mass migration that currently shows no clear signs of ending (Ivasechko, Turchyn, Astramiwicz-Leyk, 2023). It should also be emphasised that although the scale of forced migration from Ukraine is large, a significant proportion of migrants is attributed to circular migration, especially since early April 2022. This means that some people in Ukraine took advantage of the situation to implement their earlier plans (Pozniak, 2023).

There is also a material dimension to the assistance provided to refugees. Poland will spend a total of PLN 35–40 billion on aid to Ukraine in 2022. Of this, PLN 6 billion constitutes support for Ukrainian refugees paid directly from the state budget, around PLN 10 billion is aid from local governments and NGOs, while approx. PLN 10 billion is private aid from Poles. The remaining amount was earmarked for weapons (https://www.infor.pl/prawo/nowosci-prawne/5635962,Polskapomoc-dla-Ukrainy-2022-ile-kosztowala.html#ilew-2022-roku-polska-wydala-na-pomoc-ukrainie 28.05.2024).

Conclusion

Towards the end of 2021, there were indications of non-standard operations by the armed forces of the Russian Federation along the border with Ukraine. The Kremlin denied accusations that it could launch an aggression against Ukraine. The troop movements were argued to be normal activity, carried out throughout the country and resulting from the provocative nature of US and NATO activities. Contrary to these assurances, the Russian Armed Forces began striking military infrastructure facilities across Ukrainian territory on 24 February 2022, using the entire spectrum of means at their disposal (Eberhardt et al. 2023). One of the consequences of the attack was a mass flight of civilians and an immediate influx of refugees to Poland.

As the analysis of the described case shows, the refugee crisis is important in terms of the stability and security of the region, as there is a population surge in the host country. It is important to have a comprehensive approach to the refugee crisis that takes into account the protection of refugee rights and human dignity, as well as the protection of the security interests of host countries. The arrival of numerous foreign nationals is a disruptive element in the stability of social and economic life in the host country. Aid measures also represent a financial burden.

An analysis of the source materials revealed the rapidity of the Ukrainian population fleeing the effects of the war (numerous refugees in a relatively short period of time). The highest intensity of border traffic was reported in March 2022. Actions taken by the armed forces of the Russian Federation, directed not only against the Ukrainian army but also against the civilian population from the beginning of the conflict, have been brutal and ruthless, contrary to the ethics of warfare and international law and bear the hallmarks of war crimes. Poland, as a country neighbouring on the theatre of war where harm was done to the civilian population of Ukraine, has not remained indifferent, taking both formal and informal action in response to the needs of refugees.

The influx of Ukrainian refugees to Poland in 2022 has triggered a massive wave of support and solidarity and has put pressure on social systems in host countries. Refugees are usually dependent on the social assistance system of the country they have arrived in. In addition, the need to integrate the immigrant population into Polish society and to manage them in the labour market has become important. The wave of refugees was met with empathy by Poles, who voluntarily joined the relief effort. Once the refugees crossed the border, they were immediately taken care of, and further aid measures organised by the state administration were subsequently developed and implemented. They were offered social, psychological, medical and educational support. Humanitarian aid was also organised for those who remained in Ukraine and experienced extremely difficult conditions there.

According to available data, one year after the Russian aggression against Ukraine, almost 1 million Ukrainian citizens, mainly women and children, enjoy temporary protection in Poland. A total of 1.4 million people have valid residence permits in Poland (https://www.gov.pl/web/udsc/obywatele-ukrainyw-polsce--aktualne-dane-migracyjne 29.09.2023). The remainder of the approximately 2 million total entrants left Poland.

As a nation, the Poles have passed the test of humanitarianism impressively. Of course, aid could be organised better at the national level. However, the time pressure at the time and the unprecedented number of refugees are worth emphasising and no European country after the Second World War had taken in such large numbers of people fleeing the war. That is why the Poles’ aid efforts have gained international recognition. They were also reflected in the attitudes of the Ukrainian population who were very grateful to the Poles.