Introduction

Haryana, a state situated in India, has undergone significant structural transformations over the preceding decades. Initially characterized by an economy heavily reliant on agriculture, the state has witnessed substantial expansion in non-farm sectors. Parida (2015) has previously elucidated upon the growth and prospects of non-farm employment in India. Presently, the agricultural sector contributes 20.9% to the total Gross State Domestic Product (GSDP) at current prices, concurrently engaging approximately 28.2% of the workforce during the fiscal year 2020-211. These structural changes had an impact on various factors of employment in the economy and, if mismanaged, have the potential to create distress in the labour market and economy2. Recent insights gleaned from the Periodic Labour Force Surveys (PLFS) indicate a diminishing unemployment rate since 2018-19. However, the mounting cohort of unemployed youth suggests latent challenges in both the labour market and the broader economy.

The discourse surrounding employment statistics has consistently been a subject of public debate, often shrouded in complexity and opacity, rendering it challenging for the general populace to comprehend. This paper endeavours to address this inherent issue by systematically dissecting employment trends into distinct categories, thereby offering a comprehensive understanding of Haryana’s employment landscape. The analysis primarily focuses on education and sector perspectives, with findings delimited to the specific context of Haryana. Examination of the three-year trajectory in employment statistics reveals a discernible deceleration in various economic indicators during the initial two survey years. Surprisingly, the latest report for the period spanning 2019-2020 indicates an ameliorated employment situation across all facets, despite the global economic repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic during that timeframe. In light of the prevailing challenges and the imperative for a thorough investigation into labour market dynamics, this study is undertaken. Consequently, the objectives of this paper encompass (a) scrutinizing micro-trends within Haryana’s labour market, (b) examining employment indicators from a multidimensional perspective, and (c) proposing policy recommendations to alleviate the distress evident in the labour market.

Thus, this paper delineates the patterns observed in the labour force participation rate, worker population ratio, and unemployment rate across various parameters such as age, gender, region, sector, and educational level. The sector-specific analysis offers insights into the ongoing structural changes within the economy. Employment statistics pertaining to general education levels illuminate the job market dynamics for educated workers and underscore the disparities between the education provided and the requirements of the labour market. Encompassing the Periodic Labour Force Surveys (PLFS) conducted in 2017-18, 2018-19, and 2019-20, this paper succinctly encapsulates the trends derived from PLFS data, presenting them to researchers, policymakers, and other stakeholders (Kumar et al., 2023).

Globally, the labour force participation rates for the population aged 15 and above were reported as follows: Pakistan (50%), Bangladesh (57%), Australia (66%), Canada (65%), China (68%), France (56%), Germany (61%), Japan (62%), Poland (57%), United Arab Emirates (76%), United Kingdom (62%), and the United States (61%) – all significantly higher than India’s reported rate. India’s labour force participation rate (LFPR) was noted at 46% (ILO, 2022), highlighting a substantial disparity in the percentage share of the Indian labour force compared to other nations. The study in this paper focuses on labour market conditions in the state of Haryana, making the comparison between the state and national levels relevant. According to Periodic Labour Force Surveys (PLFS) data, Haryana’s LFPR was 34.3%, notably lower than India’s LFPR of 40.1%. Although a nuanced understanding is essential due to the complexity of the issue, generally, a low LFPR is associated with a dearth of quality jobs, discouraging workers from active participation in the market. The assessment of quality jobs is subjective, influenced by the economic conditions of families and educational levels. Gender-wise distribution reveals that in Haryana, the LFPR for males and females was 54.5% and 11.9%, respectively – again lower than India’s LFPR for males (56.8%) and females (22.8%). Furthermore, the worker population ratio (WPR) in Haryana was 32.1%, contrasting with India’s WPR of 38.2%. The gender-wise distribution of WPR in Haryana indicates 51.0% for males and 11.2% for females, whereas in India, the WPR for males and females was reported at 53.9% and 21.8%, respectively, significantly higher than Haryana’s figures. The unemployment rate (UR) for all age groups in Haryana stands at 6.5%, rising to 17.6% for the youth (15-29 years).

In contrast, the unemployment rate3 (UR) for all workers at the national level in India stood at 4.8%, while for the youth demographic, it was 15.0%. Consequently, the labour market distress is notably pronounced in the state of Haryana. To enhance comprehension, a comparison with neighbouring states provides a clearer illustration of the labour market challenges within the state’s economy. The labour force participation rate (LFPR) in Punjab, Rajasthan, and Himachal Pradesh was recorded at 40.8%, 41.2%, and 57.7%, respectively, surpassing Haryana’s LFPR. Within the age group of 15-29 years, Haryana exhibited an LFPR of 36.8%, whereas Punjab and Rajasthan reported higher rates at 47.9% and 43.6%, respectively. Himachal Pradesh recorded the highest LFPR at 59.4%, surpassing even the union territories. A similar pattern emerged in the worker-population ratio. Notably, the unemployment rate in Haryana is considerably higher compared to both India’s average and the neighbouring states of Haryana.

Therefore, it underscores that the employment metrics in the state of Haryana are less favourable when contrasted with its neighbouring states, the broader Indian context, and the global scenario. The elevated unemployment rate presents a significant and pressing challenge for policymakers. In this regard, the current paper offers an extensive examination of the employment landscape in Haryana.

Rationale for Haryana

The rationale for undertaking an in-depth employment analysis in Haryana stems from its commendable economic performance. Positioned as a leading state, Haryana boasts the highest per capita income among major states in the country, with the state’s Gross State Domestic Product (GSDP) consistently exceeding an annual growth rate of 8% over the past two decades. The state of Haryana has a gross state domestic product (GSDP) of 780 612 crore rupees and a per capita income of 247 628 rupees. At constant prices, the agricultural and related sectors comprise 18.9% of the GSDP. Industry and services account for 30.2% and 50.9% of the GSDP, respectively (GoH, 2021; 2020). This strategically located small state is surrounded by the national capital, New Delhi, on three sides. The state has an area of 44 212 sq. km. covering 1.34% of the total area of the country. The state has 22 districts (GoH, 2020). As per the census of 2011, the total population of the state is 253.51 lakh4 out of which 134.95 lakh were male and 118.56 lakh were female. Out of the total population of the state, 165.09 lakh (65.12%) live in rural areas and 88.42 lakh (34.88%) in urban areas. Within India’s federal system, sub-national units like Haryana wield constitutionally mandated substantial powers to oversee economic activities within their territories. The complexity of Indian labour laws, known for their rigidity and arbitrariness, falls under the concurrent list, allowing both the national and state governments to regulate the labour market (GoI, 2022). Recognizing the political sensitivity and difficulty in altering these laws at the national level, the Indian government has subtly encouraged state governments, including Haryana, to experiment with labour laws. This encouragement is evident in the readily granted permissions by the President of India for state initiatives aimed at altering labour laws. Additionally, a state-level examination provides a microscopic perspective to comprehend the dimensions of such labour market distress. Adopting a localized-to-national approach in implementing policies for addressing this distress is anticipated to yield more effective outcomes.

Overview

Employment statistics over age, gender, and region have been depicted to understand the state’s employment scenario, enabling us to make sound comments on the employment policy of Haryana. Employment issues always move around the politics and policy formulation for the state.

Employment Statistics by Age Group

Employment data concerning the entire population indicates a notably high youth unemployment rate of 17.6%. This issue is not exclusive to India, as studies by Kannan and Raveendran (2019) and Mehrotra and Parida (2017) reveal a rising unemployment trend at the national level. Within the 15-29 age group, one in every five individuals is unemployed, specifically among those aspiring to secure employment at prevailing market wages. Consequently, the youth in Haryana are experiencing distress due to the challenges posed by unemployment.

Table (1)

Employment indicators classified on age: Haryana (in percentage)

| Years | 15-29 | 15 and above | Overall population | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LFPR | WPR | UR | LFPR | WPR | UR | LFPR | WPR | UR | |

| 2017-18 | 38.6 | 30.6 | 20.7 | 45.5 | 41.7 | 8.4 | 33.4 | 30.5 | 8.6 |

| 2018-19 | 38.7 | 30.1 | 22.1 | 46.2 | 41.9 | 9.3 | 34.3 | 31.1 | 9.2 |

| 2019-20 | 36.8 | 30.3 | 17.6 | 45.8 | 42.9 | 6.4 | 34.3 | 32.1 | 6.5 |

The unemployment rate (UR) for youth in India stands at 15.0%, slightly lower than Haryana’s UR. In Punjab and Rajasthan, the youth UR is reported as 18.7% and 13.7%, respectively. Several factors contribute to the high UR, including disparities in capability and wage expectations, mismatches in skill sets versus market requirements, and uneven regional development leading to a higher opportunity cost of jobs due to potential displacement costs. (During 2018-19 and 2019-20), the 4.5% decrease in UR signals a positive trend in the Haryana state economy, but the persistently high youth unemployment remains a significant challenge for policymakers.

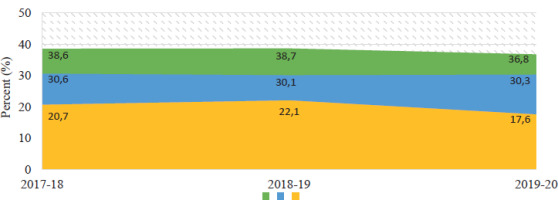

Fig. 1

Employment indicators for persons: Haryana (15-29 years age group)

Source: Calculations from PLFS unit-level data.

Moreover, both the labour force participation rate (LFPR) and worker population ratio (WPR) are considerably low in Haryana. In contrast, India records LFPR and WPR at 53.5% and 50.9%, respectively. Over the past three years, WPR has experienced a slight decline (0.3% point) in Haryana for the age group of 15-29 years, signifying economic implications and indicating a dearth of ample job opportunities. The stagnant WPR underscores the labour market distress, as reflected in the overall LFPR figures, particularly the stagnation or decline in LFPR for the youth demographic.

Employment Statistics by Gender

Examining employment patterns across genders reveals that the female labour force participation rate (FLFPR) consistently lags far behind the national average observed in other states. The current figures for 2019-20 depict an alarmingly low FLFPR at 11.9%, which is a cause for concern. Interestingly, the male worker population ratio (WPR) increased by 1.6 percentage points between 2017-18 and 2019-20. During the same period, the unemployment rate (UR) also saw a significant decline of 4.9 percentage points. This gender-based disparity in employment metrics has persisted across all three survey rounds.

Comparatively, in India, the FLFPR stands at 22.8%, still low but nearly double the FLFPR of Haryana. Notably, the remarkably low FLFPR in Haryana significantly impacts the state’s overall labour force participation rate. In Punjab and Rajasthan during the same timeframe, the FLFPR was reported at 18.9% and 28.2%, respectively. The relatively healthier FLFPR in Rajasthan, however, primarily reflects challenging economic conditions in households, compelling female family members to join the workforce despite unfavorable working conditions.

Table (2)

Employment indicators classified on gender: Haryana (in percentage)

| Years | Male | Female | Persons | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LFPR | WPR | UR | LFPR | WPR | UR | LFPR | WPR | UR | |

| 2017-18 | 53.7 | 49.4 | 8.1 | 10.7 | 9.5 | 11.4 | 33.4 | 30.5 | 8.6 |

| 2018-19 | 54.8 | 49.5 | 9.6 | 11.5 | 10.6 | 7.6 | 34.3 | 31.1 | 9.2 |

| 2019-20 | 54.5 | 51.0 | 6.5 | 11.9 | 11.2 | 6.5 | 34.3 | 32.1 | 6.5 |

The deduction drawn from the Female Labour Force Participation Rate (FLFPR) in both Haryana and Punjab clearly indicates that as household economic conditions and educational levels improve, the aspirations of females have risen. This, in turn, has led to a heightened demand for better-paying jobs and improved working conditions. Unfortunately, the economies of these states have struggled to generate employment opportunities in organized sectors, particularly in their hinterlands, resulting in the comparatively low FLFPR in Haryana and Punjab, despite their relative prosperity. In contrast, across South Asia, female labour force participation rates range from below 30% in Pakistan, India, and Afghanistan to almost 80% in Nepal and around 60% in Bhutan (Dhar, 2020).

Employment Statistics by Sector (Rural-Urban)

Region-specific employment data indicates significant structural economic changes. In terms of the overall population, the rural Labour Force Participation Rate (LFPR) remained at 32.8% in 2019-20, displaying stagnation over the years. In contrast, the LFPR for urban areas increased from 34.5% to 37.2% between 2018-19 and 2019-20. Additionally, rural Worker Population Ratio (WPR) increased by 1.0 percentage point, while urban areas saw a rise of 2.8 percentage points during the study period. Throughout this period, the Unemployment Rate (UR) stabilized at 6.5% in both rural and urban areas. However, the trends suggest that employment opportunities are relatively more abundant in urban Haryana, with the development of urban centers fostering increased job opportunities and a more efficient division of labour, thereby stimulating greater employment, and earning potential, as urban areas should ideally serve as growth engines.

When comparing the LFPR of the entire country, India’s LFPR stands at 40.8% in rural, 38.6% in urban, and 40.1% in rural+urban areas in 2019-20, surpassing Haryana’s figures. Moreover, the UR in rural, urban, and rural+urban India was 4.0%, 7.0%, and 4.8%, respectively, all higher than Haryana’s rates. In Punjab, the UR in rural, urban, and rural+urban areas were reported as 7.2%, 7.7%, and 7.4%, respectively. Similarly, in Rajasthan, the UR in rural, urban, and rural+urban areas in 2019-20 stood at 3.2%, 9.0%, and 4.5%, respectively.

The Urban LFPR for individuals aged 15 years and above increased by 3.2 percentage points, from 45.5% in 2017-18 to 48.7% in 2019-20, while it declined by 1.3 percentage points for the rural region. The Rural WPR remained almost constant, whereas Urban WPR exhibited an increasing trend during the study period. For the youth demographic (15-29 years), the LFPR in rural areas saw a decline of 4.5 percentage points, while it increased by 3.3 percentage points in urban areas.

Table (3)

Employment indicators classified in the sector: Haryana (in percentage)

| Years | Rural | Urban | Rural+Urban | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LFPR | WPR | UR | LFPR | WPR | UR | LFPR | WPR | UR | |

| 2017-18 | 32.8 | 29.7 | 9.3 | 34.5 | 32.0 | 7.3 | 33.4 | 30.5 | 8.6 |

| 2018-19 | 32.9 | 29.8 | 9.5 | 37.2 | 34.0 | 8.7 | 34.3 | 31.1 | 9.2 |

| 2019-20 | 32.8 | 30.7 | 6.5 | 37.2 | 34.8 | 6.5 | 34.3 | 32.1 | 6.5 |

It is comprehensible that the mechanization of the agriculture sector results in a significant number of workers transitioning away from agriculture. These workers, seeking livelihood opportunities beyond agriculture, encounter limited options in rural areas, especially as education levels improve and households experience relatively stable economic conditions. To facilitate structural transformation, the lure of more job opportunities or a low unemployment rate in urban areas attracts the labour force from rural regions. The migration of workers from rural to urban areas initiates a spill-over effect, fostering development in rural areas and creating additional non-farm jobs. As demonstrated by Boora & Bishnoi (2019), over 2 lakh workers have shifted from agriculture to more productive employment options in non-agricultural sectors since 2011-12. This trend is poised to intensify in the future, and the insufficiency of desirable livelihood options may emerge as a significant political, social, and economic concern in the near future, making it crucial for policymakers to address.

Distribution of Employment Statistics by Sector

This section delves into the analysis of Haryana’s sectoral employment statistics, categorizing economic activities into three main sectors – primary, secondary, and tertiary – according to the NIC 2008 code by the MOSPI, Government of India. The examination encompasses the distribution of workers across these sectors, with classification based on age, gender, and region for all three years. The objective here is to ascertain the growth rates in different sectors and assess the structural transformation occurring in the state’s economy. While previous studies (Abraham, 2009; Mitra & Verick, 2013; Mehrotra et al., 2014; Aggarwal, 2016; Mehrotra & Parida, 2017; Verick, 2018;) focused on national-level growth and structural transformation in India, Dhar’s (2020) study highlights that at the country level, female labour force participation in the industry and service sectors has risen, whereas participation in agriculture has declined. As women receive higher education, their participation in the service and industry sectors increases. Although the female labour force participation rate is gradually rising, it remains significantly below the desired comfort level. Let us explore the specific scenario unfolding in Haryana in greater detail.

Primary Sector

The primary sector encompasses activities such as agriculture, forestry, fishing, mining, and quarrying, among others. Traditionally, Haryana’s economy has been characterized as agriculture-driven. Table 4 illustrates the distribution of the labour force in the primary sector across various age groups, genders, and regions. According to the PLFS report for 2019-20, approximately 29.3% of workers are engaged in the primary sector, constituting around 27.2 lakh out of approximately 93.1 lakh workers. Within the age group of 15-29 years, about 4.9 lakhs are involved in primary activities out of a total labour force of 25.7 lakhs. The table distinctly indicates a significant departure of rural women in the youth category (15-29 years) from the primary sector during the study period, with their numbers decreasing drastically from 72% to below 29%. This shift is particularly notable for rural young women workers, given their relatively lower absolute numbers. Similarly, the engagement of youth males in the primary sector in rural Haryana has shown a decline, with less than 25% involved in the years 2017-18 and 2018-19. While this figure increased to almost 30% in 2019-20, it appears to be influenced by the economic lockdown induced by the COVID-19 pandemic from late March to June 2020. It is important to note that the PLFS data covers the period from July 1 to June 30, and therefore, the 2019-20 data include the impact of the lockdown on the economy. The notable increase in the number of workers returning to the primary sector reinforces the notion that the primary sector, particularly agriculture, serves as a reserve for the labour force.

Table (4)

Labour force share of primary sector classified on age, gender, and region: Haryana (in percentage)

In essence, workers involved in the primary sector transition to more lucrative sectors whenever the opportunity arises. This implication holds considerable significance for policy considerations, suggesting that endeavors to generate additional employment opportunities in the primary sector might not yield the desired success. Consequently, achieving higher employment growth in non-agricultural sectors becomes a crucial prerequisite for achieving structural transformation in the economy. Another noteworthy observation from the aforementioned table is that, even in rural areas, only about 45% of the workforce is engaged in the primary sector. This indicates that 55% of workers in rural Haryana actively participate in non-agricultural economic activities, demonstrating that rural Haryana has expanded beyond solely agricultural pursuits. The 6th Economic Census data from 2013-14, the latest available, reveals that approximately 6.48 lakh establishments were operational in rural Haryana, providing employment to nearly 14.64 lakh workers in 2013. Moreover, the growth in employment in such establishments between 2005 (5th EC) and 2013 (6th EC) was recorded at 3.85% per annum (GoI, 2016). The share of urban workers in the primary sector indicates the presence of a small cohort of progressive farmers who have relocated to urban areas but continue to engage in farming. Their increase in percentage from 3.6% to 4.5% in the year 2019-20 is attributed to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, as discussed in the case of rural workers.

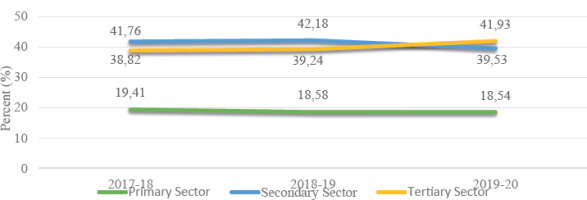

Fig. 2

Labour force share classified on sectors: Haryana (15-29 years age)

Source: Calculations from PLFS unit level data.

Examining the employment situation in neighboring states, namely Punjab and Rajasthan, reveals that in rural Punjab, 36.29% of males and 43.72% of females are actively involved in the primary sector. These percentages are comparatively lower than those in Haryana and on a national level. Nationally, 45.84% of workers are engaged in the primary sector. In contrast, both Haryana and Punjab report lower percentages of workers in the primary sector, with figures of 29.25% and 25.76%, respectively. This observation suggests that not only in Haryana but also in Punjab, workers are transitioning from the primary sector to secondary and tertiary sectors, indicating a structural transformation in the state economies. Consequently, policymakers should redirect their strategies to bolster the organized sector in non-agricultural domains, aiming to provide quality employment opportunities to educated and ambitious youth in close proximity to their home regions, thereby minimizing the costs associated with displacement for work-related activities.

Secondary Sector

The secondary sector encompasses manufacturing, electricity, gas, steam, air conditioning supply, water supply, sewerage, waste management, and construction. This sector is pivotal in driving the structural transformation of the economy. The PLFS surveys offer insights into the distribution of the labour force across these sectors at both the state and national levels. Table 5 presents the distribution of the labour force in the secondary sector across various age groups, genders, and regions. The annual report for 2019-20 indicates that approximately 23.39% of workers in India were employed in the secondary sector. In contrast, around 33.2% of workers are engaged in the secondary sector in Haryana, translating to approximately 30.9 lakh out of the total 93.1 lakh workers. Notably, the share of workers in the secondary sector in Haryana was 33.7% in 2017-18, declined to 32.8% in 2018-19, but experienced a slight increase to 33.2% in 2019-20. Analyzing the share of workers in the secondary sector in urban areas of the state reveals a sharp decrease from 44.9% to 40.5% between 2017-18 and 2019-20. In contrast, in rural regions, this share slightly increased from 27.4% to 28.7% during the same period.

Table (5)

Labour force share of secondary sector classified on age, gender, and region: Haryana (in percentage)

We now shift our focus to the age group of 15 years and above, and the trends within this age group mirror those of the overall population. The final age group of interest is individuals aged 15-29. Within this category, approximately 10.7 lakhs are involved in secondary activities out of a total labour force of 25.7 lakhs. Examining year-on-year differences in this age group, the labour force share has decreased from 42.2% in 2018-19 to 39.5% in 2019-20. Overall, the share of workers in the secondary sector in Haryana declined from 41.8% to 39.5% between 2017-18 and 2019-20. Specifically, within the 15-29 age group, the workshare in the urban sector decreased from 54.7% to 43.3%, while in rural regions, it increased from 34.3% to 37.0% from 2017-18 to 2019-20. This trend indicates a reverse migration of workers, particularly youth, from urban to rural areas due to disruptions in economic activities caused by the Covid-19 pandemic. The decline in the share of workers in the secondary sector in Haryana is attributed to the impact of the Covid-19-induced lockdown that affected the economy from March 2020 to June 2020. It is important to note that the PLFS covers the period from July 1 to June 30 in its survey, and the annual report for 2019-20 includes data up to June 30, 2020. While this reduction is viewed as a critical indicator of the Covid-19 impact on the secondary sector in Haryana, it is anticipated to be a temporary phenomenon, with a potential reversal once economic conditions stabilize in the near future.

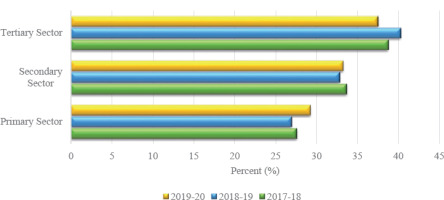

Fig. 3

Labour force share classified on sectors: Haryana (All year ages)

Source: Calculations from PLFS unit level data.

In contrast to Haryana, its neighboring states, namely Punjab, Rajasthan, and Himachal Pradesh, report that 31.81%, 23.86%, and 22.11% of workers are engaged in the secondary sector, respectively. This suggests that the proportion of workers in the secondary sector in Haryana is relatively higher at 33.2%. This is a positive indication of an evolving economy where workers are transitioning from the less productive primary sector to the more productive secondary sector. Interestingly, at the national level, only 23.39% of workers are involved in the secondary sector. Therefore, the government of Haryana and other stakeholders should capitalize on this opportunity to further enhance the structural transformation of the economy in favor of non-agricultural sectors.

Tertiary Sector

The tertiary sector encompasses wholesale and retail trade, transportation and storage, accommodation and food services activities, information and communication services, financial services and insurance, real estate, professional, scientific and technical services, administrative and supportive services, public administration and defence, education, human health and social work, arts, entertainment and recreation, other side defence services, import-export trade and support activities, activities of extraterritorial organizations and bodies. The PLFS surveys provide insights into the distribution of the labour force across various sectors at both the state and national levels. Table 6 illustrates the labour force share in the tertiary sector across age groups, gender, and regions. According to the annual report for 2019-20, approximately 37.5% of workers are employed in the tertiary sector in Haryana, amounting to around 34.9 lakh workers out of an approximate total of 93.1 lakh. From 2017-18 to 2019-20, the share of workers in the tertiary sector in Haryana exhibited a significant increase from 38.7% in 2017-18 to 40.3% in 2018-19. However, in 2019-20, the Covid-19 pandemic severely impacted the tertiary sector, resulting in a decline in the share of workers to 37.5%. Notably, for all urban workers, the share in the tertiary sector improved from 51.5% to 54.9%.

Table (6)

Labour force share of tertiary sector classified on age, gender, and region: Haryana

Conversely, in rural areas, it decreased from 31.6% to 26.8% from 2017-18 to 2019-20. The sudden decrease in the share of workers in the tertiary sector may be attributed to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, and it is expected to normalize in the near future. This implies that the share of workers in the primary sector will likely continue to decline, while it will improve in the secondary and tertiary sectors. Although the tertiary sector serves as the second parking lot for the labour force, academic literature, and empirical evidence from around the world suggest that a declining share of the primary sector is a positive indicator of a maturing economy. In this regard, Haryana is following a well-established path.

Additionally, the current agricultural census (2015-16) indicates that around 18.16 lakh landholdings are being cultivated on 36.4 lakh hectares of land in Haryana, with an average landholding size of 2 hectares. This suggests that the agriculture sector is presently employing a significant number of individuals, and a shift from agriculture is expected to improve the economic conditions of farmers and the overall state agricultural production. Within the youth category (15-29 years), approximately 9.9 lakhs are involved in tertiary activities out of the total labour force of 25.7 lakhs. The proportion of the labour force engaged in the tertiary sector in Haryana has increased from 38.8% in 2017-18 to 41.9% in 2019-20. Interestingly, there appears to be no discernible impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on the employment pattern of youth in the tertiary sector in Haryana. A closer examination reveals a notable increase in the share of urban youth workers in the tertiary sector in the state, rising from 44.8% to 55.2%. However, in rural areas, it has experienced a slight decrease from 35.3% to 33.2% during the period from 2017-18 to 2019-20.

Overall, Haryana’s tertiary sector demonstrates vibrancy by absorbing approximately 37.5% of the state’s labour force, surpassing the shares of the primary and secondary sectors. In comparison, at the all-India level, about 30.37% of the labour force is engaged in the tertiary sector. Other states such as Himachal Pradesh (21.36%), Rajasthan (22.13%), Gujarat (28.71%), Karnataka (33.65%), West Bengal (36.23%), Punjab (42.43%), and Kerala (47.31%) report their respective shares of tertiary sector employment. Consequently, Haryana’s position in this regard is notably impressive, reflecting the sound economic conditions in the state. In addition to the sectoral distribution of the workforce, another equally critical aspect is the educational level of the workforce. Education is generally associated with productivity and income, with higher educational attainments correlating with increased productivity and income. Therefore, we have also examined the educational level of the workforce in Haryana using the PLFS data.

Distribution of Employment Statistics by Education

In this section, we analyze employment statistics in relation to the general level of education. Unless otherwise specified, the default age group is considered to be 15 years and above, with youth defined as those aged 15-29. We have categorized individuals based on their general education level into three main groups: primary education, secondary education, and higher education. The trends observed are further segmented by age, gender, and region for all three years. Research conducted by Dhar (2020) suggests a positive correlation between the female participation rate and the level of education across various age groups. Additional studies by Mamgain & Tiwari (2015), Mehrotra & Parida (2017), Mitra & Verick (2013), and Singh & Kumar (2020) have been undertaken to gauge the intensity of unemployment relative to the level of education in India.

Before delving further, it is pertinent to elaborate on the educational profile of workers in the year 2019-20. Out of a total of 93.09 lakh workers in Haryana during this period, 46.07 lakh had received education up to the primary level, 28.74 lakh had education up to the secondary level, and the remaining 19.28 lakh had attained higher education. In terms of the percentage of the total workforce, 48.96% had primary education, 30.54% had secondary education, and the rest, 20.49%, had higher education. Breaking down the figures by gender reveals that out of 93.09 lakh workers, 78.55 lakh were male and 15.54 lakh were female. Further classification indicates that 37.18 lakh male and 8.89 lakh female workers had education up to the primary level, 26.24 lakh male and only 2.49 lakh female workers had education up to the secondary level. Concerning higher education, 15.13 lakh male and 4.15 lakh female workers had attained such qualifications. Region-wise distribution among the workers shows a slightly lower number of higher-educated workers in rural areas compared to urban areas. The detailed distribution of education is presented in the following sections.

Primary Education Level

The term “primary education level” refers to individuals who have completed up to the 8th class in general education. Those without any formal schooling are not categorized under primary education. In the year 2019-20, among the total workforce of 93.1 lakh, 46.07 lakh individuals (making up 49.5% of the total workforce) have received education up to the primary level. Among this primary-educated workforce, males constitute 80.7%, while females account for only 20.3%. Table 7 outlines employment statistics based on the usual status (ps+ss) for primary education. In rural Haryana, the Labour Force Participation Rate (LFPR) has witnessed a significant decrease, dropping from 40% in 2017-18 to 31.8% in 2019-20. This decline is likely attributed to the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic, where lockdown measures led to a reduction in job opportunities. Consequently, rural workers opted to withdraw from the job market, finding the available job offers and market conditions below their expectations. Another factor contributing to this decline could be the relatively high reserve wage of workers who migrated from urban to rural areas during the mid-2020 lockdown. This might have led them to choose to stay out of the labour market, further contributing to the decrease in rural LFPR in 2019-20. Examining the rural LFPR in Haryana reveals a positive trend initially, with male LFPR improving from 66.1% in 2017-18 to 71.8% in 2018-19. However, it witnessed a decline in 2019-20, as previously discussed. In contrast, the rural LFPR for females presents a concerning scenario. Starting just below 13% in 2017-18, it further dropped to an unacceptable level of 7.5% in 2019-20. This extremely low female LFPR in rural Haryana reflects the challenging working conditions for women, limiting opportunities for them to join the workforce.

Table (7)

LFPR, WPR, and UR (in percent) According to Usual Status (ps+ss) by Primary Education Level for Haryana

Empirical evidence indicates that as a household’s economic condition improves, women are often the first to withdraw from the labour market during the initial stages of the development process. The participation of women in the labour market could see improvement if the subsequent phases of development offer quality jobs, uphold the dignity of labour, and provide favourable working conditions. In the case of Haryana, the persistently low female Labour Force Participation Rate (LFPR) in rural areas suggests a lack of quality jobs and acceptable working conditions. Unfortunately, these challenging working conditions for women extend to urban areas, as highlighted in the preceding table. Urban LFPR trends in Haryana mirror those in rural areas, with a decline in LFPR for males in 2019-20 and an already low LFPR for females further decreasing during the same period.

Analysing the unemployment rate (UR) over the study period reveals intriguing patterns. In rural areas, the total UR increased from 13.8% in 2017-18 to 21.9% in 2018-19 but surprisingly decreased to 13.1% in 2019-20. Conversely, urban Haryana experienced a more drastic fall in UR, dropping below 3% in 2019-20. Notably, in rural Haryana during 2018-19, male UR rose to 23.9%, while female UR reached its lowest level at 0.4%. Exploring the reasons behind this unusual phenomenon requires a more detailed investigation, especially considering that in 2019-20, rural UR for both males and females returned to the levels of 2017-18 despite disruptions in normal economic activities. It’s worth mentioning that the Labour Force Participation Rate for youth in Punjab (50.9%), Rajasthan (52.0%), Himachal Pradesh (60.6%), and Uttar Pradesh (37.3%) surpasses that of Haryana (35.4%). Therefore, Haryana’s LFPR is comparatively lower than its neighbouring states. This discussion exclusively pertains to the workforce with primary education only.

Secondary Education Level

The classification of the secondary education level pertains to individuals who have acquired education from the 9th to the 12th general education class. In Haryana, a workforce of 28.73 lakh individuals (constituting 30.9% of the total workers in the state) is reported to have employment up to the secondary level. Among these workers, 26.24 lakh are male, and only 2.49 lakh are female, emphasizing the pronounced gender imbalance in the Haryana workforce, as previously discussed.

An examination of the educational profile of the workforce is presented in Table 8, detailing employment statistics for individuals with education beyond the secondary level, categorized by the age groups of 15-29 years and 15 years and above. In the youth age group (15-29 years), the LFPR, WPR, and UR for the year 2019-20 were reported as 32.4%, 26.5%, and 18.1%, respectively. Additionally, the LFPR for males and females in this age group stood at 53.2% and 5.1%, respectively. Over the period from 2017-18 to 2019-20, both LFPR and WPR exhibited an increasing trend for males and females. Furthermore, UR showed a positive trend by decreasing from 22.4% to 18.1%, though it remains relatively high. The UR for males decreased from 19.7% (2017-18) to 17.6% (2019-20), while a significant drop was observed in female UR from 45.9% to 24.2%. Notably, female UR was higher in rural regions (31.4%) compared to urban regions (14.9%) in the 15-29 years age category. Conversely, there was not much deviation in UR for males between rural (17.7%) and urban regions (17.4%) in the same age category.

Table (8)

LFPR, WPR, and UR (in percent) According to Usual Status (ps+ss) by Secondary Education Level for Haryana

When comparing Haryana with India and its neighbouring states, India’s Labour Force Participation Rate (LFPR) stands at 29.0%, followed by Punjab (35.8%), Rajasthan (25.1%), Himachal Pradesh (50.8%), and Uttar Pradesh (25.9%). Although Haryana’s LFPR (32.4%) is relatively higher than the national average and neighbouring states like Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh, it notably falls below that of Himachal Pradesh. Therefore, the LFPR of youth in Haryana does not meet the desired standards.

Regarding the Unemployment Rate (UR), Haryana’s status is less favourable. Haryana’s UR is higher than its neighbouring states such as Himachal Pradesh (6.9%), Rajasthan (7.4%), and Uttar Pradesh (11.0%). In contrast, Punjab’s UR (24.9%) surpasses that of Haryana (18.1%). The national UR is 13.5%, indicating that Haryana’s UR is comparatively higher for individuals with secondary-level education. In the age category of 15 years and above, LFPR, Worker Population Ratio (WPR), and UR are reported as 46.6%, 42.2%, and 8.2%, respectively. Haryana’s UR (8.2%) is higher than Punjab’s (10.0%), but lower than Himachal Pradesh (2.6%), Uttar Pradesh (4.2%), and Rajasthan (4.0%), as well as the national average (5.8%). Consequently, the UR in Haryana is relatively high for individuals with secondary-level education.

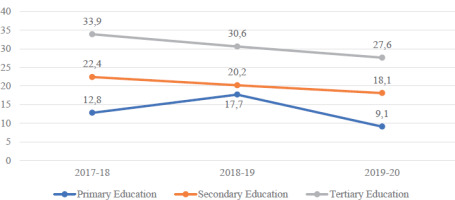

Higher Education Level

Higher education pertains to individuals who have achieved educational levels beyond the 12th grade, including graduation and above. Table 9 illustrates employment statistics for individuals with higher education in two age groups: 15-29 years and 15 years and above. In the youth category (15-29 years), the Labour Force Participation Rate (LFPR), Worker Population Ratio (WPR), and Unemployment Rate (UR) were reported as 49.9%, 36.1%, and 27.6%, respectively. The UR for primary, secondary, and higher-educated youth was 9.1%, 18.1%, and 27.6%, respectively. Notably, the highest UR was among higher-educated youths, twice as high as secondary education and three times higher than primary education, indicating a significant unemployment issue. One in three higher-educated youths is unemployed.

Table (9)

LFPR, WPR, and UR (in percent) According to Usual Status (ps+ss) by Higher Education Level for Haryana

Meanwhile, the LFPR for males and females was 70.7% and 24.6%, respectively. From 2017-18 to 2019-20, LFPR for both genders showed a decreasing trend, with marginal WPR decrease for males and improvement for females. Although UR decreased from 33.9% to 27.6%, it remains high. Male UR decreased from 28.2% (2017-18) to 24.7% (2019-20), while female UR sharply declined from 57.2% to 37.7%. Female UR was higher in urban regions (39.9%) than in rural areas (33.2%). Male UR showed minimal deviation between rural (25.0%) and urban regions (24.3%) in the 15-29 years age category. Haryana’s LFPR (49.9%) is lower than India’s (58.8%), and compared to neighbouring states like Punjab (68.9%), Rajasthan (58.3%), and Himachal Pradesh (77.3%), it lags behind. Concerning UR in higher-educated youth, Punjab (25.2%), Rajasthan (38.6%), Uttar Pradesh (30.5%), and Himachal Pradesh (28.8%) also face high unemployment rates. While Haryana’s UR (27.6%) may be somewhat justified in comparison, it remains notably high.

Fig. 4

Unemployment and Education levels: Haryana (15-29 years age)

Source: Calculations from PLFS unit level data.

In the age category of 15 years and above, the Labour Force Participation Rate (LFPR), Worker Population Ratio (WPR), and Unemployment Rate (UR) were reported as 58.4%, 51.4%, and 12.0%, respectively. Notably, LFPR and WPR were higher in this category than in the youth category, whereas the UR for individuals aged 15 years and above (12.0%) was less than half of that observed in the youth category (27.6%). Males in this age group reported LFPR and WPR as 79.2% and 70.7%, respectively, while females reported LFPR and WPR at 30.3% and 25.3%, indicating a significant disparity between the LFPR and WPR of males and females. Overall, the LFPR of women is considerably lower than that of males across all education levels. Regarding UR, it was higher for females (16.4%) than for males (10.8%) among higher-educated workers. However, the UR of youth (27.6%) was more than twice that of individuals in the 15 years and above age category (12.0%). Interestingly, the LFPR of youth was lower than that of the 15 years and above age category.

Consequently, the unemployment rate is higher among youth compared to other age categories, and there is a direct correlation between the level of education and the extent of unemployment. Gender-wise statistics indicate that the unemployment rate is consistently higher among females than males across different education levels. Region-wise statistics reveal that the unemployment rate is higher in rural than in urban regions across various education levels. However, higher education leads to increased unemployment among Haryana’s youth, attributed to factors such as the scarcity of quality jobs, the prolonged duration of job searches, and the high cost of migration. Nevertheless, the unemployment rate in Haryana is comparatively higher than in neighbouring states.

Way Forward

Over the past few decades, Haryana’s economy has undergone a significant structural transformation, maintaining a growth rate exceeding 8% in Gross State Domestic Product (GSDP) for the last two decades. This transformation is characterized by a declining share of the agricultural sector and a rising share of the services sector in the GSDP. The organized sector is predominantly cantered around the National Capital Region (NCR) of Haryana, including cities like Gurugram and Faridabad, where new job opportunities have emerged. Haryana stands as one of the wealthier states in India in terms of per capita income. Consequently, workers within the state, whether semi-skilled, skilled, or highly educated, possess a higher displacement cost compared to workers from outside Haryana. Their expectation of remunerative job opportunities, given their sound economic background, contributes to the high unemployment rate, as low-paying jobs are less attractive to them.

To address this, there’s a suggestion to shift job opportunities from urban centres like Gurugram and Faridabad to the hinterland areas of Haryana. This shift could significantly impact the high unemployment rate by reducing the displacement cost for local workers. The improved regional infrastructure in Haryana makes the transition of industries to hinterland areas feasible. However, the sole focus on unemployment rate to gauge the labour market condition could be misleading. Unemployment hides much more than it revels. Hence, it is time for economies to pay attention to all the indicators with special focus on LFPR and WPR. Seeing in this context of Haryana, though UR has reduced in recent surveys, but LFPR has not shown proportionate changes. Withing LFPR also, the focus of employment policies should be to increase WPR. This process might trigger unemployment rate initially, but will eventually help to solve larger problem of labour markets and providing access to reap demographic dividends to the economies.

Conclusions

The reduction in the unemployment rate is not proportionately matched by a relative increase in the worker-population ratio in Haryana. Consequently, the primary reasons behind the state’s low Labour Force Participation Rate (LFPR) have been attributed to the disparities. Particularly noteworthy is the remarkably low female LFPR in Haryana, which has had a downward impact on the overall labour participation rate in the state’s economy. Additionally, a sector-wise analysis of the workforce reveals a shift among young workers from primary and secondary sectors to the tertiary sector. Notably, labour force participation rates and worker population ratios are significantly higher at advanced education levels compared to primary and secondary education. Conversely, the unemployment rate is also higher at this education level. Despite these trends, it’s worth mentioning that the female LFPR is relatively better at higher education levels than at primary and secondary education levels.

In an overarching perspective, the sector-wise distribution illustrates the growth of the tertiary sector in terms of employment, indicating a structural transformation in Haryana’s economy. Higher levels of education contribute to increased labour force participation. However, this pattern seems incongruent in Haryana, where there is heightened distress among highly educated youths. Consequently, these micro-trends highlighted in this paper necessitate attention, forming the basis for the development of an effective employment policy for the state.