Introduction

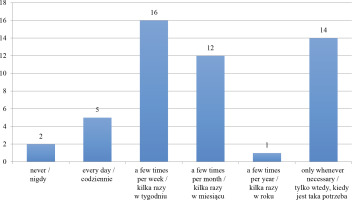

The modern world presents many challenges to parents – some of them emerge every day, whereas others give them some time to prepare, but not always fully. This is how we can define adaptation to the world of the media, new technologies or Internet – in spite of many preparations, it is impossible to be fully prepared for changes that follow. One of the challenges of modern education, both for children and for parents, is adequate preparation within the scope of media education. The latter should give answers to questions asked by modern parents: How much time should our child spend in front of the screen? What is the safe amount of screen time? At what age it is proper to buy a phone to a child or to set up a social media account for him/her? How to set the rules? It turns out, however, that the Internet most often helps parents find the right answer (Fig. 1). This results in the strong need to ensure proper preparation for the use of electronic devices, not only among children but also parents.

Figure 1

A screenshot with the most frequent prompts in searching an answer to the question about screen time

Source: www.google.pl (access: 30.08.2023).

The aim of the research was to check what knowledge of media education parents of primary school pupils in grades 1-3.

Media education in literature on the subject

In the digital world, the precise definition of the term ‘media education’ becomes a difficult task due to the presence of many similar issues in the area of generally understood digital security, digital security science and the rapid development of many media. The term ‘media education’ has been subject to various transformations resulting from the emergence of ever newer types of media. The first media of this kind were related to film, television or audiovisual education, but the rapid development of the media led to the commencement of scientific reflections on the uniform concept that would fit all emerging means of communication. In 1973, the first definition of media education was made during a meeting of member organisations of the International Film and Television Council in Paris (Ptaszek, 2019, p. 123). At that time, media education was defined as ‘research on, learning and teaching modern means of communication and expression forming a specific autonomous area of knowledge within the scope of educational theory and practice different from the use of these means as an aid in teaching and learning other areas of knowledge, such as mathematics, nature or geography’ (Ptaszek, 2029, p. 123). In this sense, media education was supposed to prepare recipients for contact with the media – it was not to serve as a science about the use of the media in teaching, but as the media science in itself – as a support tool in understanding media within various scientific disciplines. Until the emergence of computers and the Internet, the definition of media education was subject to minor transformations, but in the course of the widespread use of this medium, UNESCO decided to expand this definition. First of all, it covered all kinds of the mass media (means of mass communication), indicating that media education ‘enables people to understand means of mass communication used in their society, as well as the ways they work and acquire the skills of using them, for the purpose of communication with others’ (Ptaszek, 2019, p. 127).

Taking scientific disciplines into account, media education forms a part of media pedagogy. Among areas of operation of media pedagogy, Bronisław Siemieniecki mentions general media pedagogy, media education, information technology, computer diagnostics, pedagogical therapy and the media in the human world (Siemieniecki, 2021, p. 100). He assumes that ‘media education covers the didactic and educational process in all forms of main education, further education and self-education, the methodology of media and IT training, and the technology of education’ (Siemieniecki, 2021, p. 100). He does not indicate that media education should cover only the stage of kindergarten or school education – he points out that its area of operation concerns the pupil/student, the teacher and their environment, including cyberspace. In his opinion, media education ‘is used for teaching recipients to choose information consciously, making them familiar with the language of media communication, raising awareness about the culture of communication, stimulating interest in culture, shaping socially desirable attitudes and developing creative activity with the use of the media’ (Siemieniecki, 2021, p. 101). Piotr Drzewiecki defined media education in a similar way – as a part of media pedagogy. He indicated that media pedagogy is understood as ‘a science about upbringing through media education – the practice of such upbringing that encompasses not only the communication of cultural values but also education and the didactic process’ (Drzewiecki, 2013, pp. 21-22).

The term ‘media education’ was explained in Encyklopedia PWN [PWN Encyclopaedia], where it is defined as ‘an interdisciplinary area of education describing the role of mass communication in the socialisation, learning and upbringing process, preparing for the use of the multimedia and for the smooth communication and reception of information via new technologies and preparing for the critical reception of senses of visual and media education’ (Encyklopedia PWN, 2023). In Popularna Encyklopedia Mass Mediów [Popular Encyclopaedia of the Mass Media], the definition proposed by Józef Skrzypczak specifies media education as ‘a direction of education aimed at providing children, young people and adults in specific knowledge and skills enabling them to receive media messages in a conscious and critical manner, particularly with regard to the mass media messages, and to use the media as tools for description of the world, intellectual development and mutual communication’ (after: Granat, 2019, p. 32).

Another explanation of this term was provided by the National Council of Radio Broadcasting and Television, where the amended directive on audiovisual media services from November 2018 introduces the following definition of media education: ‘media literacy refers to skills, knowledge and understanding that allow citizens to use media effectively and safely. In order to enable citizens to access information and to use, critically assess and create media content responsibly and safely, citizens need to possess advanced media literacy skills. Media literacy should not be limited to learning about tools and technologies, but should aim to equip citizens with the critical thinking skills required to exercise judgment, analyse complex realities and recognise the difference between opinion and fact.’ (KRRiT, 2018) Another definition of media education was formulated by Wacław Strykowski: ‘media education is aimed at understanding the nature and impact of the media and their rational and effective use in didactic and educational situations (Strykowski, 2003, p. 19).

When analysing definitions of media education, it is worth noting a relatively new type of differentiation used by Grzegorz Ptaszek, who divides media education on the basis of media development phases: Web 1.0, Web 2.0 and Web 3.0. Analogously, he mentions:

media education 1.0 – its aim was not only to develop critical thinking towards the media and their messages but also to indicate the critical attitude and autonomy in general. It referred mainly to television and the press;

media education 2.0 – connected mainly with the development of the Internet, including social media websites, it was intended to pre- pare recipients for responsible reception of the traditional media and messages provided by new media. Its aim is to increase aware- ness in the fields of reception, communica- tion and creation in the media space;

media education 3.0 – extends the area of interest with the technological sphere of the media that is invisible to users (algorithms, data) and refers to all hidden and smart mechanisms related to the activity of recip- ients; its aim is to increase the critical anal- ysis of the entire media ecosystem by point- ing out not only one’s own media activity but also the significance of the impact of smart algorithms (Ptaszek, 2019).

The differentiation used by Grzegorz Ptaszek shows precisely what challenges are faced by recipients of the media and the Internet, including both adults and children, at particular stages of their development.

Theoretical ref lections are worth supplementing with the goals set for media education. Wacław Strykowski mentioned such goals as:

preparation for the proper (critical) recep- tion of the media as tools used for communi- cating information and shaping the system of values and attitudes;

preparation for the use of the media as tools of intellectual work (self-development) and professional work (entrustment of some ac- tivities to the media);

preparation for the rational use of the me- dia as instruments of fun and entertainment (Strykowski, 2003).

Anna Kaczmarek draws our attention to media education in terms of its purpose, indicating that ‘the aim of media education is to develop media competence, which consists, among others, in access to all media, teaching the skill of analysing the content of media messages and becoming familiar with communication possibilities in the modern media. And media competence should be understood as a harmonious composition of knowledge, understanding, evaluation and the efficient use of the media’ (after: Nowicka, 2020).

The above reflections clearly suggest that the media education process starts not at the school stage but earlier in the family circle. Beata Kosmalska highlighted this fact in her research paper, indicating that media education can be considered from two perspectives: the formal one and the informal one. The formal perspective usually involves the implementation of goals of media education provided at compulsory and optional classes within institutions. The informal perspective occurs in various non- school structures of the social environment. The most important one is obviously the family circle, where media education starts and where children are prepared for the development of media competence by other environmental entities (Kosmalska, 2019). Kosmalska indicates that it is the responsibility of parents to introduce the child adequately into the world of the media and digitisation. In order to achieve this, the parent should have the relevant knowledge and understanding of what media education is in the modern world and should introduce it into their own life independently. These aspects were noticed by Agnieszka Ogonowska, who explains that media education addressed to parents will help them enrich their competence. It may concern such areas as: characteristics of the new media, threats resulting from the use of the latest technologies, methods of limitation and prevention of the pathological use of the media, the modelling of positive media behaviours in the home environment, or the implementation of home media education (after: Nowicka, 2020).

Focusing around the concept of media education in Poland, we must devote some attention to the understanding of this term in the European and international arena. In foreign language on the subject, media education is defined by the term ‘media literacy’, or ‘media literacy education’, which is generally understood as the ability to use the media. Many foreign authors indicated that ‘education in media literacy is the key to understanding modern information in society: people are simply obliged to have media competence today, otherwise they will not only become easy targets of numerous media manipulations but they will not be able to enter the diversified world of media culture to the full extent’ (Fedoro, Mikhaleva, 2020, p. 155). One of the leading organisations acting in the field of media education in USA is The National Association for Media Literacy Education (NAMLE), which defines the skill of using the media as ‘the ability to access, analyse, evaluate, create and act by means of all forms of communication’ (Lwandik, 2023, p. 7).

Since the accession of Poland into the European Union, trends in the development of media education in Poland are determined mainly by European directives and acts regulating media education activity. For the last few years, member states have been bound by the latest directive EU 2018/1808, which was adopted by the Parliament and the Council on 14th November 2018. In the context of the understanding of this directive by member states, it is interesting to note that, depending on the country, the term ‘media education’ is translated here in various ways. Ewa Murawska-Najmiec notes that ‘the English version of the directive contains the definition of media education (media literacy) that is generally understood as a result of media education, whereas the French language version refers to media education (or, strictly speaking, to education for the media – éducation aux médias). However, the Polish translation of the directive does not use any of these terms; instead, it uses a descriptive form ‘the ability to use the media’ (Murawska-Najmiec, 2012, p. 75). This differentiation indicates how ambiguously particular countries approach the issue of media education and explores the lack of homogeneity in the treatment of this concept by EU authorities. One of the most recent measures undertaken by the EU was the publication of ‘European Digital Action Plan’ in 2020, according to which the EC intended to work on the preparation of common guidelines for teachers and educators in order to support digital skills and counteract disinformation in member states. The outcomes of the implementation of this plan were to be verified in 2023.

Directions of action in media education are also determined by international organisations that constantly undertake a number of actions and campaigns addressed to parents, teachers and children with regard to the improvement of their media competence. One of them is the UNESCO, which strives to popularise new global standards with regard to guidelines concerning the elaboration of curricula on the use of the media and information (after: Lwandik, 2023). Significant measures are taken also by the UNESCO, including the most recent one – the implementation of the UNICEF’s Strategic Plan 2022–2025, the aim of which is to call for activities to solve the issue of the digital gap or increase of security of virtual spaces by presenting both positive and negative aspects of media activity (after: Lwandik, 2023).

Methodology of research

The aim of the paper is to analyse the knowledge of parents about media education. Referring to theoretical reflections, the author formulated the main research problem: Do parents of children at the stage of early school education possess knowledge about media education? The main problem was divided into the following two detailed research questions:

How do parents introduce media education into their children’s lives?

What threats and opportunities from the me- dia and the Internet are known to parents?

For the purposes of the research, the diagnostic survey method was used. The technique used was the survey, and the survey questionnaire served as a research tool. The author’s questionnaire consisted of 34 open and closed questions and a demographics. The questions were addressed to parents of children at the stage of early school education – in Grades 1–3 of primary school. The survey research was conducted fully online via Google form in August 2023. Altogether, 50 parents – mainly women – took part in the survey.

Characteristics of respondents

Most of the respondents were women (45); only 5 answers were provided by men. Places of residence indicated by respondents included cities (34 persons) and villages (16 persons). The dominant group among respondents was formed by parents at the age of 31-40 (37 persons) and at the age of 41-50 (11 persons). The smallest group of respondents consisted of persons at the age of up to 30 years (2 persons). The respondents are parents of children from Grade 1 (16 persons), Grade 2 (16 persons) and Grade 3 (18 persons).

Knowledge of media education among pa- rents – results of research

It is worth starting the analysis of the research by presenting answers where, according to parents, children spend a safe amount of time in front of the screen during the period of early school education. Respondents had an opportunity to enter their own answers according to the interpretation of the question. Most parents reported the amount of 2 hours (13 answers) and 1 hour (13 answers); the answer ‘1-2 hours’ was also frequently given (8 persons), and two persons indicated 2-3 hours as the right amount. Other questions were more diversified, including the following examples: ‘There is no safe amount, everything is up to the child’, ‘0.5 hours per day, like a goodnight cartoon in the past’, ‘6 hours a week’, ‘Preferably nothing at all. At home, TV or the tablet should be used as rarely as possible, maximum once a week. Unfortunately, this opportunity is lost at school…’, ‘25 minutes per day,’ ‘up to 3 hours per week’, ‘20 minutes – three times a week’, ‘3-4 hours per week’, ‘More on the weekend, less during the week. Everything is a question of learning, how much time it takes’, ‘Hard to say’, ‘3 hours daily’, „Two hours during school time’. The above answers clearly show the diversity in the amount of safe screen time reported by parents; this shows the diversity of the approach to the use of electronic means and different levels of knowledge about the safe quantity of screen time in children from that age group.

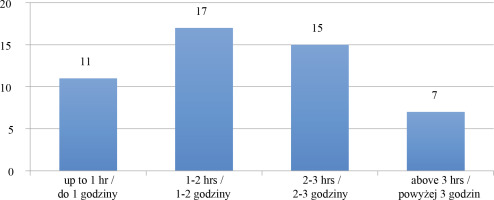

Chart 1

Daily time declared by parents as spent ‘in front of the screen’ by their children

Source: based on own research.

The results indicate that a majority of respondents declare that their children do not spend more than two hours with electronic media – 17 persons stated that their child spends 1-2 hours a day, 15 persons – 2-3 hours and 11 persons – up to 1 hour. The smallest group consisted of parents whose children spend more than 3 hours in front of the screen. The juxtaposition of the two aforementioned results shows that the time spent by children in front of the screen is consistent with what parents indicated as the safe quantity of screen time.

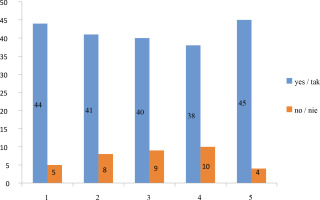

The guidelines of media education refer also to knowledge about the possibility of parental control, also in the form of an app, and, primarily, knowledge of the existence of such applications – Chart 2.

Chart 2

The use of the possibility of parental control (in an app) in the case of the use of electronic devices by the child

Source: based on own research.

According to the results, almost one half of the respondents do not feel the need to use apps supporting parental control (22 persons), whereas some more parents declare that they have a permanent control time set up in the app (16 persons), and a few respondents indicated that they would also individually determine the time of using the screen for each day (10 persons). Only two respondents did not know that there are apps allowing for parental control. None of the parents indicated any answer related to the freedom of use of the screens by children.

A majority of the surveyed parents (40 persons) admitted that they set the rules of using electronic devices with their child. Persons who declared that they set the rules together with their child indicated how they do it. The obtained answers referred to a number of areas – the first area concerned the arrangement of the time for which children are allowed to sit in front of the screen: ‘We set the day and time for watching a cartoon, once a week,’ ‘Before each use, there is a fixed time and scope of what he/she can do’, ‘2 hours a day’, ‘He/she can use the computer after finishing his/her assigned tasks’, ‘At what time he/she can use it’, ‘Before the child takes the tablet, I say how much time he/she can spend with it’, ‘I inform how much time he/she can spend and ask him to turn the device off after this time,’ ‘We fix the time and what they are allowed to watch’, ‘How much time and what apps he/she can use’, ‘We set dates, times and rules of use’, ‘He/she sits in front of the screen only when his/her homework is done,’ ‘We talk and set the time, depending on the duties and plans of our family.’ The second area concerned the control of the contents reached by the child – parents indicated the following answers: ‘I tell him/her not to watch YouTube channels, but he/she sometimes does not comply, so I deleted the app’, ‘What he/she can watch and for how long’, ‘ We choose for our child the websites he/she can use at the time determined by us’, ‘There is the time and the websites he/she can use’, ‘We set the time of using electronic devices and control the contents that are displayed’. ‘We spend time with the children in the same room in order to ensure control’, ‘I must know what my child views and I control the contents watched by the child’, ‘For example, we agree on what he/she must not watch’, ‘He/she has to inform me about all games, and I check the phone’, ‘We agree upon the safety rules, apps, websites’. The third area of answers suggested the presence of a conversation: ‘We make a compromise’, ‘During a conversation about the threats of excessive use of such activity’, ‘Talking and negotiating’, ‘We talk and present our expectations’, ‘We talk, and if there are any problems at school, I limit the screen time’, ‘We discuss things every day’, ‘We talk about what is allowed and what is not, what is valuable and what is not’. The numerous and diversified answers of parents show that they represent very different levels of knowledge about the implementation of media education.

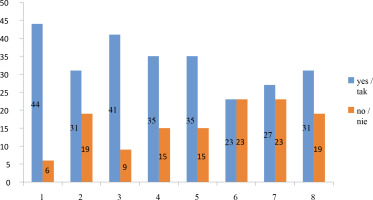

The knowledge of positive and negative aspects of the use of electronic devices by children is a part of the preparation for supporting the child within the scope of media education in the family circle – Chart 3 and 4.

Chart 3

The knowledge of positive aspects of using the Internet among parents.

Source: based on own research.

1. Extension of information competence, 2. Development of passions/interests, 3. Opportunity to contact friends and parents, 4. Support in daily learning, 5. Source of knowledge.

Chart 4

Knowledge of the consequences of excessive use of electronic devices

Source: based on own research.

1. Reduced concentration and attention, 2. Sleep disorder, 3. Nervousness, 4. Neglect of school or household duties, 5. Reduced physical activity, 6. Resignation from passions/hobbies or extracurricular activities, 7. Wrong perception of oneself or one’s body, 8. Aggression/cyberbullying.

Most respondents are familiar with positive aspects of using the Internet: extension of information competence, development of passions/interests, opportunity to contact friends and parents, support in daily learning, source of knowledge. Some respondents indicated they do not have such knowledge. Apart from benefits, the use of electronic devices has also drawbacks – Chart 5

Among the reported consequences, parents indicated most frequently that they are familiar with reduced concentration and attention (44 persons) – it is one of the most characteristic features of excessive use of electronic devices. Then they indicated nervousness (41 persons), the neglect of school or household duties (35 persons) and reduced physical activity (35 persons). The negative aspects that are least known to parents include the wrong perception of oneself or one’s body (23 persons) and resignation from passions/hobbies (23 persons) – the same number of parents declared that they know or do not know such a consequence of using electronic devices. Few parents are familiar with sleep disorder and aggression, too (19 persons each).

The use of electronic devices is inseparably connected with web surfing, which often involves numerous dangers that children may experience.

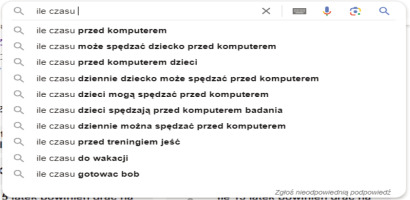

According to the results, most parents talk about online security with their children; differences lie in the frequency of holding such conversations. The biggest number of parents declare that they talk with their children a few times per week (16 persons), slightly fewer respondents (14) said that they talk with their children about it only when such a conversation is necessary. A similar number of parents declare that they talk about online security with their child a few times per month (12 persons). Two respondents do not talk about it with their children at all, and one declared they do it a few times per year. The obtained data show that parents pay attention to the online security of their children and try to talk to them about it regularly. In order to hold such a conversation properly, parents should have adequate knowledge about online security. According to the research, 21 persons do not make use of educational aids, training courses or thematic literature. Other persons indicated the following places that help them expand their knowledge: ‘Online articles’, ‘Uncle Google knows everything’, ‘Webinars, training courses for parents’, ‘Safe Internet training’, ‘I have training courses at work because I work 8 hours at the computer and this is a must for every employee’, ‘Online training courses’, ‘Books, websites with webinars for parents’, ‘Training at work’.

Another research area was an attempt to determine the level of children’s knowledge in their caretakers’ opinions.

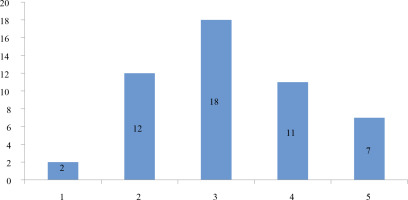

Chart 6

Knowledge possessed by children about the use of screens according to parents

1 – none (the child is not aware of dangers, does not take care of data security, does not comply with the rules)

5 – high (the child is aware of dangers, can take care of data security, complies with the rules)

Source: based on own research.

Making use of the five-stage scale, the surveyed parents did not indicate clearly that the level of knowledge about the use of screens by their children is high (7 persons) or none (2 persons). Most parents declared that children have a moderate level of knowledge (18 persons), which means that one of the aforementioned aspects is not fully carried out by them. The low level of knowledge was declared by 12 surveyed parents and the average level was reported by a slightly smaller group (11 parents). In the context of media education, the certainty of parents that children possess knowledge of the rules of using screens to a lesser or bigger extent is a positive aspect.

One of the sources of knowledge can also be school classes responding to the needs of media education – e.g., related to online security or the rules of use of electronic devices. Over one half of respondents said that they do not know if such classes are held in the school attended by their children, 14 respondents know about such classes, and the lack of such classes is declared by 7 parents.

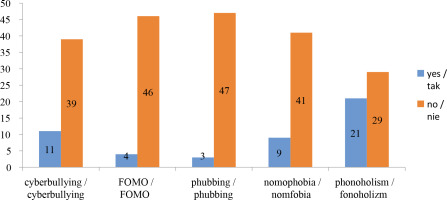

The results of the research show that most parents are familiar with terms concerning online security and the use of electronic devices. Most parents are familiar with phonoholism (21 persons), one half less know cyberbullying and a few are familiar with nomophobia.

More than one half of surveyed parents shared their answers about how they understand the concept of media education. The following answers were the most similar to the definition of media education:

Learning to use the media wisely and safely. At that age, first of all, I try to teach my chil- dren that the virtual world is not the same as the real one, that it cannot be more important. I pay attention to the contents they view, try- ing to suggest what is valuable and what is just a waste of time. I convince my children that commercials do not always tell the truth, and the image of people in social media has little in common with reality (I have three girls). The issue of threats, including data theft, is a riv- er topic, but I bring it up whenever there is an opportunity to present an example right away.

Information what programs are suitable for the child’s age and what are not, what contents he/she may watch and what he/she may not, how many hours he/she can spend in front of the screen, why screens are harmful and why they can be used only sporadically. The values I want my child to cultivate and deepen knowl- edge about. I want him/her to be exposed to many stimuli in the real world rather than the virtual one.

Education on the smart use of the Internet, where to look for the information we need, awareness that information found on acciden- tal websites may be wrong, on online security, on the protection of privacy in social media, awareness that not all contents are valuable, on the lack of tolerance for online hate, on haz- ards to health resulting from the long use of screens.

Most other answers indicated that parents associate media education with passing knowledge about the media and the Internet; secondly, they associate it with the awareness about the use of electronic devices and then indicate that it is an educational aid or helps to obtain knowledge. Parents’ answers divided into areas are shown in Table 1.

Table 1

Concept of media education

Some of the answers referred to the significance of this phenomenon in the modern world: ‘Sadly, it is unavoidable’, ‘An important part of functioning in these days’, ‘It is important, like the multiplication table in the past’, ‘A socially important issue’, ‘A necessary tool to function in society’. The collected material contained also answers that were difficult to combine with the above distinctions and clearly indicated the things with which parents struggle: ‘A failure, a source of conflicts, I do not know how to handle it,’ ‘I think that more pressure should be put on the parent in this case’, ‘There is currently excessive access to bad content and information that sometimes leads to the child’s aggressive behaviour when he/she watches YouTube channels’. There were also two answers ‘I do not know’. Looking at the above opinions of parents about media education, we can notice how differently they look at this issue.

Summary and conclusions

Media education whose task is to prepare society for the proper use of available means of mass communication is not just the skill of using a phone or laptop – it is also the awareness of media impact, which can be both positive and negative. When analysing international trends in terms of media education, we can notice a higher commitment of countries to the implementation of systemic actions aimed at raising the awareness of citizens about the use of the media. These actions increasingly often encompass not only adults but also young people, children or seniors. Individual countries subordinate their educational activities to requirements set for them as members of the EU, UNESCO or another organisation. Also, many countries take a range of additional actions that largely go beyond the national state strategy to address the needs of their society. One of such countries is Finland, which implements a much larger strategy than the one applying within the scope of a European directive. Most of the undertaken activities fall under the Department of Media Education and Audiovisual Media within the Ministry of Education and Culture. One of the dynamically operating non-governmental organisations is the Finnish Society on Media Education, which plays an important role, also in the international arena, through activities addressed not only to the country’s citizens. The organisation is supported by the Ministry of Education and Culture. This example shows the role that national policy can play in media education.

Looking at Poland, it is difficult to notice clearly any actions undertaken by the government. It turns out that even EU regulations imposing media education activity in the country are not implemented at the appropriate level. Poland does not have a uniform national strategy regulating the issues of media education, and a majority of activities are carried out within the Ministry of Education and Science and the Ministry of Digitalisation. Information about activities conducted in the field of media education is available on the website of the National Council of Radio Broadcasting and Television; however, the latest entries were published at the end of 2022. As in many other countries, the Polish education system lacks the subject ‘media education’, and actions are undertaken within the scope of subjects taught in the core curriculum. An increasing number of non-governmental organisations try to address the needs of media education. They undertake the education of children and young people, as well as their parents, for the purpose of their adequate preparation for the reception of the media. Media education is constantly an issue of concern for researchers and scientists, including media experts, who highlight the increasing need to introduce systemic changes in the national approach to media education during the preparation of conferences and materials.

The primary goal of the present research was to check if parents of children at the stage of early school education possess knowledge about media education. The results concerned the understanding of media education by parents of children in the period of early school education, indicated the level of parents’ knowledge about the online security of children and the time spent for surfing online. The respondents also answered how they understand the concept of media education. The presented results indicate that parents possess knowledge about media education. Looking in detail at the obtained answers, we must say that this knowledge is very varied. Few of the surveyed parents can precisely define the concept of media education as the entire process where not only the use of knowledge but also its acquisition, skills and critical analysis are important. The results show that not all parents understand media education as an opportunity to teach children how to function properly in the media world; for some of them it is a support tool in the daily school education process. Interesting opinions were also expressed by parents who indicated that media education is a difficulty or challenge to them. The results showed that concepts related to phone addiction or cyberviolence, such as cyberbullying, FOMO, phubbing or nomophobia, are unknown to many parents. Few of the surveyed parents undertake to obtain professional knowledge about education from training courses, online publications or books. Their knowledge is, therefore, based on their own experience, which may prove insufficient to support their child in the media education process in the course of time.

The collected material made it possible to analyse the ways in which parents introduce elements of media education into their children’s lives. According to research, many of them regularly talk about online security and about the rules of using electronic devices. Such conversations are held between parents and children at least once a week or once a month. In many cases, parents talk to children only when this is necessary. Thus, conversations are one of the elements of media education. Apart from talking about online security, parents introduce also the rules of use of electronic devices by children. Few of the surveyed parents use apps dedicated to parental control; most of them agree upon the rules of using the screens with the child, instead of making decisions independently. This allows us to conclude that they do not only try to impose rules on their children, but also to understand their needs in the use of electronic devices. Consequently, children gain a broader awareness of their own impact on how they can use a computer, tablet or phone. In the future, this will help them use electronic devices consciously.

The above results of research showed that threats and opportunities on the part of the media and the Internet are known to a majority of surveyed parents. Parents associate the world of the media and electronic devices not only with threats – they notice also the opportunities that it offers to their children. Among negative consequences, they indicated most frequently that they are familiar with reduced concentration and attention, nervousness, the neglect of school/household duties and reduced physical activity.

To sum up, we can say that parents of children at the stage of early school education possess knowledge about media education, try to acquire it and pass it to their children in an adequate manner. They also try to follow their children with regard to their use of electronic devices. The question is: how long will they be able to do so if their current knowledge is not clearly systematised and supplemented?