Introduction

Identifying the mechanism of regional cultural and economic diversification is not an easy task. It is performed both by evoking stadial concepts of development and by research aimed at diagnosing non-economic stimulators of economic activity. Jacek Kochanowicz (2010a), following Max Weber (1994), notes that values, perceptions, or ideas largely explain the rise of capitalism, and thus determine regional diversity in development. We cannot be certain, however, that the economic area is shaped entirely by the ideosphere. The dispute over the primacy of consciousness over being, and vice versa, remains an unresolved issue to this day. Undoubtedly, however, it is necessary to recognize the coexistence of two antagonized schools of explanation, Weberian and Marxist, and the relationship between economy and culture.

Jacek Kochanowicz notes that: ‘the presentation of some general model of the relationship between economy and culture, within which it would be possible to conceptually manipulate cultural variables in order to determine how they affect economic variables, is yet to enjoy its realisation’ (Kochanowicz 2010a: 14). This task, however, has been undertaken repeatedly, at every turning point in the world: during the industrial revolution, the crisis of legitimacy of capitalism, the ‘discovery’ of the Third World, the domination of the Asian tigers, or in the era of globalization (Kochanowicz 2010a: 11-12). ‘Momentous time’ also mobilizes the effort to identify the mechanism of regional diversification in Poland, as Polish economy is entering the next stage of development. Expectedly, it will probably correspond to a completely different axiological background and guiding narrative.

The purpose of this article is to diagnose the axiological and economic diversification of Polish regions, along with indicating the mechanism of diversification and providing forecasts for the future. The starting point in the analysis involves the stadial concepts of development, which lead to the exposition of a key typology in terms of further consideration. This typology makes it possible to divide the history of the world, as well as modern regions according to the assignment to culture: honour, achievement and joy. The very concept of ‘culture’, as Janusz Hryniewicz (2004: 190) aptly notes, ‘serves [in turn] to explain the processes of individual behaviour becoming more similar and the formation of homogeneous collective behaviour’. Concurrently, it allows to take into account axiological interpretations of the development process.

The requirement for a multifaceted analysis mobilizes the adoption of an appropriate (reductionism-free) tool, i.e. the category of the culture of economic development, which, following the proposal of Antonina Kłoskowska (2007), forces a diagnosis of the mechanism of diversification in the following aspects: material, social and symbolic.

Development in the perspective of stadial concepts

In classical sociological theory, the explanation of the development process is addressed by three schools: evolutionist, modernizationist and dialectical. All of them, without exception, take up the issue of describing the auto-dynamic process of cumulative change, and the first two particularly emphasize the passage of societies through ‘stages of development’. The stadial description was pioneered by evolutionists, including the intellectual father of sociology – August Comte (1961) and his ‘Victorian’ successor – Herbert Spencer. Each successive stage of development means, for evolutionists, ‘a transition from simplicity to complexity and from fluidity to permanence’ (Sztompka 2010: 106). However, the dichotomous scheme of stadial analysis finds many later continuators in the persons of Émile Durkheim and Ferdinand Tönnies, among others. For the former, a legitimate typological criterion that separates the different stages of development is the so-called ‘moral density’, which is a measure of the intensity of relationships. The transition from the next stage of development in this case means increasing the internal complexity of the system (Durkheim 1999). Ferdinand Tönnies (1988), on the other hand, sees the typological criterion in the concept of ties, whereby he also stretches the development line between community (Gemeinschaft) and society (Gesellschaft). He additionally attributes another type of will to the self-indicated stages of development: organic (Wesenwille) or arbitrary (Kürwille). The criterion of ties allows him to finally free the discussion of development from the systemic trap. The next stage of development is not only a structural and functional complication of the social whole, but above all a new quality of the space of interpersonal interactions. This fact is more strongly exposed by researchers set in the realities of the 20th century. David Riesman (1950) ascribes social character types to stages, and anthropologist Margaret Mead (1978) explains the developmental process by restructuring intergenerational relationships. The importance of relationships is also acknowledged by Daniel Bell (1974), who is considered a technicist. Moreover, the reference to this category provides typological framework for the development. The stages he distinguished: pre-industrial, industrial and post-industrial can be described by the dominance of a particular type of relationship (Bell 1974: 116). They are referred to as game against nature, game against machine, game against fabricated nature or game between persons. These stages correspond to ‘Tofflerian waves’ (Toffler 1986).

However, the division of development into stages is often accompanied by an evaluation. Lewis Mumford (1966) outlined the ‘risk profile’ of subsequent stages. In doing so, he proposes to distinguish three (stages) in the development process: eotechnical, paleotechnical and neotechnical. The latter is to result in a new standard and quality of life (Mumford 1986: 207). However, this will only be possible if the progress of technological improvement is accompanied by an axiological transformation, or in other words: the development of a new ‘culture of the spirit’. In this way the stages of development can be attributed to their respective axiology. Ronald Inglehart even argues that the mechanism of the development process boils down to axiological transposition. According to this researcher, development is made possible by moving from one value to another. Economic initiative, on the other hand, is fostered only by post-material values, i.e. the trust, tolerance and individualism, so valued by Francis Fukuyama (1997).

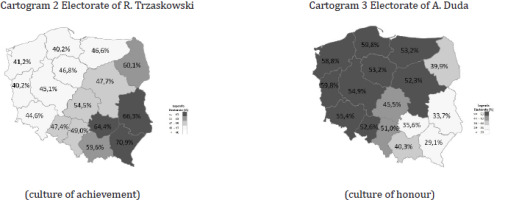

The ‘axiological route’ accompanied Inglehart in further research, which he conducted together with Miguel E. Basáñez (2016). In it, they distinguish three types of cultures, which correspond to successive stages of development and at the same time indicate their ability to co-occur. This means that they are not only arrangeable in a chronological order, but can also become a tool for typologizing and evaluating current differentiation. The basis of the typology proposed by Inglhart and Basáñez is Shalom Schwartz’s axiological cube (Figure 1). The structure of the cube is determined by three axes: politics, economics and society. The first axis is a combination of hierarchy and egalitarianism; the second axis is a continuum between harmony and interference with nature; the third axis marks the bridge between rootedness and autonomy. On the figure thus constructed, Basáñez places three cultures, defined as honour, achievement and joy.

Figure 1

Axiological cube

Source: Basáñez M. E., 2016, A World of Three Cultures: Honor, Achievement and Joy, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

The culture of honour is placed at vertex A. It represents the culmination of hierarchy, harmony and rootedness. This culture is inherent in primitive societies with expressive and authoritarian leadership. A high degree of interdependence and subordination to authority and the laws of nature can be identified in this culture. However, the culture of honour can be modified over time, ‘moving’ around the edges of the cube. There are three paths for the development of this culture: economic (embedding at point B), political (embedding at point C) and social (embedding at point E). In the first variant, development involves improving production techniques; in the second, it is related to increasing production and labour productivity; in the third, it boils down to specialization and diversification of the social structure.

The culture of achievement, on the other hand, is placed exactly in the opposite corner (H). At point H, the planes of egalitarianism, autonomy and interference with nature converge, whereby the importance of individual aspirations increases in the culture of achievement, and the world is seen as susceptible to transformation and worth conquering. At point H, there is also a demand for new predispositions: entrepreneurship and rationality. However, the transition from the honour vertex (A) to the achievement vertex (H) is not possible along a direct path. At the same time, Basáñez notes that antagonized cultures can only be ‘reconciled’ by a balanced solution. This solution is the culture of joy, embedded in the centre, rather than in any of the vertexes of the figure. The central value of this culture is belonging, with harmony as its principle. This culture is referred to as a culture of joy and is based on the principle of axiological balance. It is an ‘area of axiological equilibrium’ in which the social rooting of economic development takes place. It is also the ‘territory’ where the currents of individual aspiration meet and reconcile with the need for subordination to the community. At the same time, the culture of joy emphasises the category of quality of life and combines performance ambitions with respect for nature. As such, it is also not a simple continuation of the development line indicating the direction of the transition from tradition to modernity, but rather a balancing point of the radicalisms contained in the axiologies of the cultures of honour and achievement.

The culture of joy, although geometrically located in the middle of the block, between the cultures of honour and achievement, is chronologically the last one. As such, it represents a way of crowning the past history. However, the division between the cultures of honour, achievement and joy can be discussed not only in a historical context. This distinction can become the basis for identifying modern diversification mechanisms.

Axiological rooting of the development process

A reductionism-free diagnosis of the diversification mechanism requires emphasising the axiological perspective. This perspective has a long research tradition. Its pioneers are two antagonized disputants: Max Weber (1994) and Werner Sombart (2010). The former, noting that Protestant countries were developing faster, ‘brought’ asceticism beyond the walls of abbeys, thus making Beruf (profession) a kind of vocation and an overriding determinant of development. According to Weber, the idea of predestination was supposed to mobilize accumulating wealth. As a result, a lifestyle previously reserved exclusively for abbeys (vita anachoretica) became the founding element of the capitalist economic order (Weber 2005: 59-61). Werner Sombart (2010), on the other hand, attributes the ‘capitalist spirit’ to the David’s Tribe. According to this researcher, it is Judaism that economically differentiates Europe. Sombart argues that faster development is occurring in those areas where business is being taken over by Jews. This religious group is mobilized for entrepreneurship by the category of ‘holiness’, understood as the obligation to arrange life according to the contract. The relationship with God is a kind of bargain, and wealth is a commitment and an instrument of service, not a means to achieve individual intentions (Attali 2003: 23-24).

David S. Landes. argues, however, that ‘adherents of all religions, as well as the non-religious, can grow up to be rational, conscientious, orderly, efficient, well-ordered people [...]’ (Landes 2005: 208). This means that although development is an axiologically driven process, it cannot be attributed to one particular religion. Following this line, Landes postulates that the importance of predestination and other ‘religious inventions’ should not be overestimated. Rather, it was other factors, concurrently present with the primordial principles of Protestantism or Judaism, that found their way into economic productivity. These include the ability to read, which is a natural and religiously obligated skill for Protestants and Jews. The trap of religious monopoly is also dismantled by other researchers, including Ronald Inglehart and Mariano Grandona. While the former argues that development consists of moving from a material to a post-material value system, the latter, making a distinction between intrinsic and instrumental values, argues that only the former dynamises the economy. They are also absolute in nature, and while they do not serve specific, identifiable goals, they do stimulate development. This is because they allow the participants to defer gains over time and focus on the long-term perspective (Grandona 2003:103). Shumel Eisenstadt, on the other hand, makes a distinction between axial and non-axial civilizations. This researcher, not without good reason described as a ‘non-Marxist Marxist’, has proved the existence of non-material stimulators of the development process (Ben-Rafael, Sternberg 2009:21). According to him, the mechanism of development is founded on the internal conflict between the different parts of the social whole. However, this is not about Karl Marx’s prominent partnership between ‘consciousness and being’ or ‘base’ and ‘superstructure’, but rather about the content of the ideosphere. As Eisenstadt (2009:34) notes, ‘at the core of civilization is the symbolic and institutional interplay between, on the one hand, the formulation, propagation, articulation and constant reinterpretation of the basic ontological visions prevailing in a given society, its main ideological premises and supreme symbols, and, on the other hand, the definition, structure and regulation of the main areas of institutional life [...]’. Development involves aligning institutional facilities with an ontological vision of the world. The transcendental order, while interacting with the secular one, sets developmental process in motion. (Eisenstadt 2009:121). Consequently, it becomes known as a ‘push towards transcendence’, an expression of ‘messianic hope’, representing a prophecy of ‘possibility, choice, and freedom’ (Fromm 2013:25). ‘Awareness of the gap between the transcendental and secular reality’ ultimately legitimises development, which must be understood as a process grounded in values.

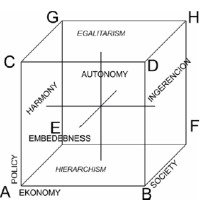

The axiological perspective ultimately makes it possible to plot the cultural-economic map of the world and thus illustrate the issue of regional diversification. It should be noted that this challenge has been addressed by many including Huntington Samuel (1976), or Mugueal Basáñez (2016). The latter divided the world according to the order derived from Schwartz’s model. They compiled the obtained results in a graphic, referred to as a ‘conceptual triangle’. Their proposed scheme shows that the culture of joy is most representative of Catholic European countries: Spain and Italy. The culture of achievement, on the other hand, is typical of Nordic countries, and the culture of honour is most prominently displayed in Islamic countries (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Conceptual triangle

Source: Basáñez M.E., 2016, A World of Three Cultures: Honor, Achievement and Joy, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

The axiological map of the world allows us to conclude that ‘stages of development’ are useful not only in historical-comparative analysis, but also constitute the foundation of the most current typologies. This is because the different types can co-occur, dividing the different areas between them. At the same time, it should be noted that this division must be discussed in both global, continental and national contexts (Szczepański, Śliz, Geisler 2011:9).

Innovation culture as an analytical category of regional diversification

Diagnosis of the mechanism of regional axiological and economic diversification requires the use of a properly constructed tool, namely the concept of innovation culture. It builds on the now classic proposal by Antonina Kłoskowska (2007). This researcher distinguishes three layers of culture: being, social actions and symbol (Kloskowska 2007:76). The culture of being (otherwise known as the material layer) includes the physically accessible creations and tangible effects of human activity. Social (or societal) culture is an area of activity. It manifests itself in the relationships, social roles and activities of social actors. Symbolic culture, on the other hand, is the realm of values and signs. It is ‘the matrix by means of which the human spirit gives shape to reality’ (Kłoskowska 2007: 75). The different categories (layers) of culture are used in the analysis of the development process. The first (material) layer allows us to look at innovation as if it were the result of techno-economic preparation of the system. As such, it has to be conditioned by the infrastructure and economic performance of the region – GDP per capita, among other indicators. The material layer is embodied in patents and innovative technologies implemented for the first time. With its help, it is possible to diagnose not only the state of production, but also the innovative potential of the region. At the same time, this layer is the result of the activity of social actors and a ‘trace’ of their economic initiatives, which, in a strict sense, should be assigned to the next layer of innovation cultures, i.e. the social layer. Its measure includes the entrepreneurial practices and economic/implementation initiatives of social actors. Its affluence, in turn, is determined by the region’s social capital, which is measured not only by personal contacts and trust, but also by involvement in various initiatives, including participation in associations or voter turnout. Social capital is ‘the second invisible hand’ of the market (Kotarski 2013:25), that determines the course of its development. It is the power to achieve goals that would not be possible without cooperation and trust (Coleman 1988:98). Authors of the Social Diagnosis (Pol. Diagnoza Społeczna) (Czapiński, Panek 2015: 351-363) argue that social capital affects development by facilitating negotiations, or lowering transaction costs. Janusz Czapinski’s team identifies a positive relationship between social capital and GDP per capita. Social capital shows a relationship with the third layer of innovation cultures – the symbolic layer. This type of capital is based on an assimilated habitus, and this has to be tied to the dominant value system. Jerzy Bartkowski (2008) argues that components of social capital such as family ties, religiosity and local communities are stronger in the area of historic Galicia. The contribution of the region’s axiology to the culture of innovation thus seems to be significant. It is the symbolic layer of culture that exposes its significance most clearly. The basis for its recognition is the division proposed by Inglehart and Basáñez into a culture of honour, achievement and joy. It allows us to identify the axiological background of the regions, which is contributed by the analysis of the ideological background, conducted on the basis of information on the results of political elections. The diagnosis of the symbolic layer makes the consideration of the axiological condition of development seem feasible, thus highlighting the theses flowing from the research of Weber (1994), Sombart (2010), or Inglehart (2003).

Identification of the mechanism of regional development diversification

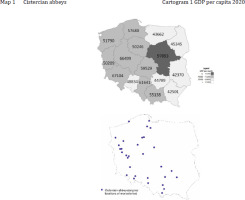

For hundreds of years, Poland’s territories have been marked by a division into two distinct cultural and economic areas. The continuity of this division is best illustrated by the juxtaposition of two maps: the distribution of Cistercian abbeys (original locations, mainly from the 11th and 12th centuries) and the regional distribution of GDP per capita in 2015 (Map 1; Cartogram 1) (Zdun 2018: 123-130). The first map is an illustration of the process of civilising Eastern European lands in the 11th and 12th centuries. This is when the expansion of the Cistercian order based on civilising and evangelising expansion took place. The location of the monasteries of this congregation was sought by the authorities of the time. Cistercian orders economically revitalized the areas in which they appeared, which resulted from the congregation’s specific rule of St Benedict of Nursia. The combination of prayer and work became the ideological backbone of medieval innovation centres (Eberl 2011). The Cistercians, in the name of the ‘glory of God’, perfected not only the art of cultivation, but also engaged in industry (including mining, metallurgy, and weaving), and wherever they settled, population, workshops and crafts began to increase in numbers. The process of spreading the spirit of economic initiative was adopted by the rule of the monastery, which was reflected in the involvement of converts in the economic work of the monastery. There were usually three of them per one monk. At the same time, the Cistercians travelled from West to East in their mission, establishing branch abbeys not far from one another. With their activities and ideas, they thus infected more and more distant corners of Europe, but did not cross the border defined by the western bank of the Vistula (Map 1).

Figure 3

Source: Own compilation based on GUS BDL data and information on abbey locations (www.szlakcysterski.org).

The economic division of Poland’s modern territory seems to uphold the ‘Cistercian order’. This is demonstrated by the regional variation in GDP per capita. One can notice a significant overlap of higher GDP areas with Cistercian areas. This juxtaposition allows us to maintain Janusz Hryniewicz’s thesis about the power of the cultural import process (Hryniewicz 2004). According to this thesis, the economic differentiation of Poland’s regions is determined primarily by proximity to the Western world, rather than by the burdens of a partitioned past.

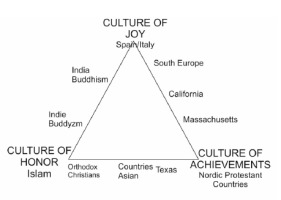

But will the ‘Cistercian division’ continue? If so, what axiologies determine its persistence? The concept of Basáñez (2016) and research conducted in this area (Zdun 2018) allows us to conjecture that the culture of innovation within the boundaries corresponding to the common territory of Poland, is still forming, with the confrontation of opposing axiologies as its ideological context. The most current measure of it is the results of the recent 2020 presidential election. The political decisions of Poles have had an axiological context for years, and the electorates of the various parties can be characterized using the core values that make up Shalom Schwartz’s so-called circular scheme (1992). Included in this scheme are elements like benevolence, universalism, security, self-direction, tradition, adaptation, achievement, stimulation, hedonism, and power (Pilch 2012:129). Research conducted as early as 2012 in Polish regions based on Schwartz’s scheme shows that ‘different value systems lie at the root of ideological preferences, described on the left-centre-right dimension’ (Pilch 2012:135). At the same time, analyses of political orientations allow us to conclude that the left-right divide, refers mainly to the socio-cultural area. This division is further identified with the distinction between the post-communist and post-Solidarity camps. (Kwiatkowska, Cześnik, Żerkowska-Balas, Stanley 2016:98). Concurrently, analyses by Bohdan Jałowiecki, Marek S. Szczepański and Grzegorz Gorzelak (2007: 80) show that a constant regional variation can be observed in elections (both parliamentary and presidential). This is also demonstrated by Tomasz Zarycki (2002), who claims that region is the primary political context. A survey conducted by CBOS (2020), on the other hand, makes it possible to plot the ideological profiles of voters of the two rival presidential candidates: Rafał Trzaskowski (who is associated with the liberal PO party) and Andrzej Duda (corresponding with the conservative-nationalist current of the Law and Justice party). The CBOS (2020) survey also makes it possible to conclude that Andrzej Duda was the candidate of older, less educated and less financially well-off people (often with per capita household income of PLN 1,000). Ideologically, these voters declared right-wing and nationalist political views, showed devotion to religion and tradition, seeing Andrzej Duda as a defender of values and a promoter of national pride. The group argued its choice with a high evaluation of the President’s ethical actions, while expressing satisfaction with the pro-family and social policies. By the same token, it should be said that this electorate is ideologically closer to the culture of honour, which values belonging to the community, the role of authoritarian leadership, the importance of tradition and religiosity in public life. Rafał Trzaskowski’s voters, on the other hand, can be described as more progressive, well-off and better educated voters. They are people with leftist or centrist political views and are less religious than the average. Ideologically, these voters are to be associated with moral liberals (including support for LGBT) and opponents of social benefit policies, because of which, they are also still closer to a culture of achievement than the culture of joy. At the same time, this electorate expects competence rather than charisma from its president, although it values in them such qualities as tolerance, kindness, and respect. To a large extent, however, they pay attention to the expertise of their president. All this makes it possible to associate this group more with a culture of achievement, which is ideologically closer to liberal worldview and opposes moral and economic conservatism.

Spatial analysis of these variations allows us to uphold Basáñez’s thesis (2016), according to which the current, third stage of development emerges not by contradicting previous models, but as their confrontation. In the case of the Polish territory, a particularly interesting thing becomes apparent, namely the overlap of territorial and ideological confrontation.

In addition, this division documents previously noted trend concerning support for the conservative candidate in economic regions. The question is, do these opposing axiologies show a connection to a more current measure of development, i.e. the innovation index?

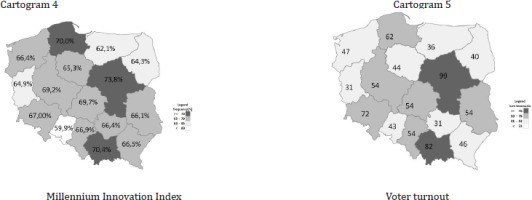

The innovation index at the regional level demonstrates the country’s considerable diversity. It is a completely different and, it seems, better fitting form of diagnosis of social economic development. Innovation is therefore an important comparative category today. Research by the EU Commission (EIS 2022) shows that innovation is still a challenge and an expected future for Poland. Currently, Poland is positioned as an ‘emerging innovator’, ahead of only Lithuania, Bulgaria and Romania. Consequently, the Innovation Index will be used for this analysis. It will take the form of the indicator prepared annually by Bank Millenium, aggregating data at the same (provincial) level as the National Electoral Commission. The Innovation Index of Bank Millennium (Millennium Index) is based on five simple indicators. These are: labour productivity, R&D expenditure, post-secondary education, R&D sector workforce, number of patents. This makes regions with strong economic and educational potential fare best in the comparison. As it turns out, the regional variation of this indicator breaks the division between the eastern and western parts of the country sanctioned by historical influences (Cartogram). Innovation thus marks a new stage in development, in which advancement is determined not only by material factors, resources and infrastructure, but also the role of other (human and social) types of capital is marked. This is also evidenced by subsequent summaries. As it turns out, the regional distribution of the innovation index interacts not only with the material attitude of development (GDP per capita), but also shows a relationship with voter turnout, which should be considered a measure of social capital. At the same time, no connection can be noted between the Millennium Index and any idological camp.

Figure 5

Source: Own compilation based on Bank Millennium and data from the National Electoral Commission.

The correlation matrix prepared below corresponds to the structure of the aforementioned innovation culture category. It contains variables that hint at all three layers of culture:

GDP per capita – material layer

Turnout – social layer

Electorates – symbolic layer (culture of honour vs. culture of achievement)

Table 1

Correlation matrix

The above results prove that Poland is divided into two axiological zones: the culture of honour and the culture of achievement. At the same time, they delineate areas that are economically different, but only in terms of traction. The honour culture candidate’s election score achieves a negative correlation of -0.40 with GDP per capita (at the limit of statistical significance for p>0.05). Concurrently, the same result with the opposite sign determines the relationship of achievement culture to this traditional property of development. This only confirms the previously noted difference in voter characteristics: Trzaskowski’s voters come from economically better-off regions. To a governmental extent, however, these axiologies do not explain innovation itself, which is an indicator that captures development using entirely different parameters. The correlations of the two ideological camps with the Millennium Index are close to zero and cannot be considered statistically significant. Consequently, it cannot be said that innovation is fostered by the progressiveness associated with the culture of achievement, and hindered by the tradition that is the ‘face’ of the culture of honour. Determinants of innovation must be sought elsewhere. It is evident that its material base must be conducive (hence the high correlation of the Millennium Index with GDP per capita). However, the relationship between voter turnout and the innovation index was seen as particularly interesting, with a positive correlation of 0.77 meaning that social capital (with turnout as its measure) explains as much as 66% of the innovation index on its own. This, in turn, allows us to postulate the possibility of identifying the cultural imponderables of innovativeness. As it turns out, these imponderables are not equated with progressive or conservative views, but rather the very habitus of the innovator, part of which is the willingness to act and take matters into one’s own hands.

Final Conclusions and Summary

The results make it possible to derive several conclusions and justify the predictions made earlier. First, the classic indicator of economic development (GDP per capita) has a strong positive relationship with regional innovation indexes. At the same time, the innovation indexes show regional variation, partially breaking the division between the western and eastern parts of the country. Innovation indexes must be regarded as a new measure of development that is relevant for the times. These indexes make it possible to estimate the key innovation potential for modern economies. Innovation indexes report not only on the technological or economic background of development, but also emphasize social issues. The exposition of the social capital category must also be linked to it. This category shows a strong relationship with GDP per capita (0.72) and an even stronger relationship with the innovation index (0.77). Second, economic development has a certain axiological context. The accumulated data allow us to conclude that the xenophobic and Eurosceptic culture of honour does not contradict innovation, just as the culture of achievement paradoxically does not support it. Based on these results and other studies presented by Czapiński (2015) and Bartkowski (2008), among others, it cannot even be ruled out that the area of honour culture could become a storehouse of valuable resources for an innovative economy. It is, after all, an axiological environment, and as such is more strongly focused on the issue of community, ties, family, i.e. the building blocks of informal social capital.

Following Basáñez, based on these results, the next stage of development must also be anticipated. It is likely to emerge from the reconciliation of the hitherto antagonized axiological communities. This is because a culture of honour cannot become a laboratory for an innovative economy per se. It needs to reject its own burdens (which stem primarily from excessive attachment to tradition, overreaching conservatism and ‘international scepticism’). This culture will have to adopt the values typical of the culture of achievement, with cosmopolitanism and a strong commitment to competence as its valuable resources. The model of an innovative economy, however, reports a great demand for the activity of social actors. The model of an economy with innovation as its pillar cannot draw only on a material base. It needs even more of what is quintessentially a third axiology, which, for now, is not yet clearly revealed at the regional level. That axiology is known as the culture of joy, the quintessence of which is harmony and balance. The activity of social actors (turnout) should also be most strongly associated with it. And so it seems that the future belongs to a culture of joy, with social capital as its main pillar. In the culture of joy, values such as quality of life, health, family come to the fore. It is no coincidence that these value unite Polish citizens (CSO 2018). This is also how Basáñez’s concept comes to fruition in Poland – symbolically and territorially. One notes an ideological dispute that further perpetuates the historical East–West divide. From this division, however, another stage of development and type of culture emerges, which needs to be tied to the axiology of balance, typical of the culture of joy and social capital being its best expression. So, too, the culture of joy, being an analytical tool, must eventually serve something more, since its ideal-typical formula, reveals a diversification mechanism. The history of the economic development of Polish regions is the proof that import of ideas from the Western world is accompanied by the passage through stages of honour, achievement and joy. At the same time, the consideration concerning the long-time dominance of the division between the axiology of honour and achievement seems legitimate at this point. Nowadays, one can observe on the territory of modern Poland a plethora of qualitatively unprecedented ‘event’, namely a ‘clash’ of antagonised cultures. The result of this collision is likely to manifest itself in a new economic model and its corresponding balanced culture. And therein also lies the principle of the diversification mechanism and the opportunity for innovation.